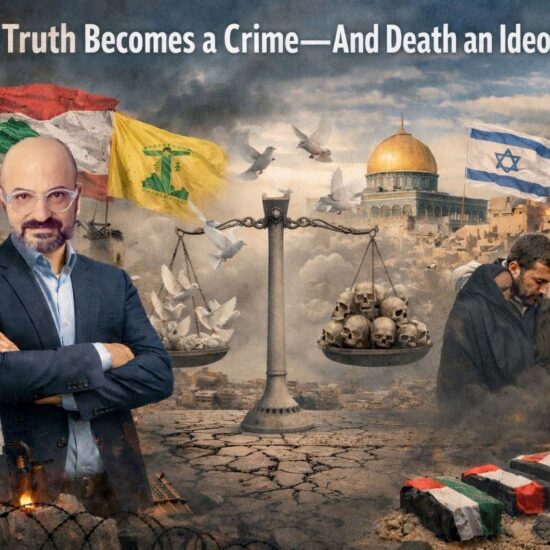

American troubled foreign policy in the Middle East, the question on how to respond to it, and the irrelevance of Lebanon

Donald Trump and Kamala Harris had their highly anticipated debate on September 10. There was some back and forth involved, but on the issue of the Gaza war, both candidates practically said the same thing, without really presenting what their foreign policies in the Middle East would look like beyond emphasizing Israel’s ‘right to defend itself against Iran and its proxies.’ None of this is surprising, and US foreign policy in the region is unlikely to change of its own accord. How is it that politicians in the superpower speak of us in mere talking points without challenging the consensus?

US foreign policy in the region is renowned for its many mistakes, without any genuine attempt at reform reaching its happy conclusion. In recent memory, Barack Obama appeared to enthusiastically support the Arab Spring protests in Egypt, Libya, and Syria. In Syria, he set ‘red lines’ regarding Assad’s use of chemical weapons, only to backtrack on them later. He also dedicated most of his presidency to signing a nuclear deal with Iran, which he did in 2015. As a result, he ended up empowering tyrants and autocrats across the board. Trump and Biden would prove even worse for the region.

Naturally, this did not endear America to the Arabs, as they actively blamed America for all their problems. The events of the last year, including America’s unconditional support for Israel’s genocide in Gaza, dealt a crushing blow to any popular support for America for most Arabs. As the war is about to enter its first year, the perceived inability of the US to secure a ceasefire deal has given an impression of weakness, especially after Benjamin Netanyahu addressed Congress last July to wide fanfare. The image of standing ovations aroused intense protest from nearly all over the region and elsewhere.

One thing we have always struggled to look at objectively is how we respond to American policy. Over the past few decades, the Middle East has witnessed strong waves of popular protests against America’s role in the region, which further intensified in the runup to the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. As the public sphere in the Arab world was gradually eroded by political repression, war, and socio economic crises, the discourse on America in the Arab world was gradually absorbed by lunatics, rejectionists, and supporters of Russia and China, who believed these nations cared more about us than America.

In Lebanon, we are in a much tougher bind than Arab countries: we have no natural resources, no geostrategic importance, and no semblance of political order or stability. Therefore, in America’s calculations, we are absolutely irrelevant. We hear a great deal of condemnation on America’s behaviour in the region, but what has any Lebanese politician or intellectual done to address the Americans with clear demands? What kind of backing would such an individual have? We don’t even bother trying to address Americans in a language they understand, let alone sympathize with as we enter the sixth year of socioeconomic collapse.

A common slur thrown at anyone who attempts to reason with American politicians is that of a traitor. Given the rightful view of the US as an unconditional supporter of Israel and its interests, public figures are hesitant to try and engage American audiences, let alone politicians. In this respect, the Israelis have mastered the game of communicating with Americans from the top down. Regardless of what you think about the Israeli lobby, Israeli politicians and pundits know that engaging Washington was key to their interests, and have therefore devoted a great deal of time and effort into this strategy.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah authorized negotiations with Israel, under the auspices of the Biden administration and its Israeli-born envoy, to secure a maritime demarcation deal with the Israeli government in October 2022. Why would Hezbollah get a break for going this deep into negotiations with Israel under American auspices but others won’t? Last month, when MP Mark Daou participated in the Democratic National Convention as an invited guest, he was harshly criticized, and even branded a traitor, by pro-resistance media pundits. This sort of monopoly on political action with the world’s superpower does us more harm and doesn’t protect our interests.

Let us ask ourselves a simple question: when was the last time a high ranking American official visited Lebanon? If memory serves, the last such official was Joe Biden, who visited Lebanon when he was vice president in 2009. If memory serves, also, the last time a Lebanese politician or head of state was received in the White House was in 2017, when Donald Trump received then prime minister Saad Hariri in the White House, even holding a joint press conference with him. Token gestures? Could be, but right now we might as well be a nameless pariah state.

No one is under any illusions that the United States only considers Lebanon or many Arab states when conducting its foreign policy, especially as it continues to support Israel. However, this does not have to be a fait accompli. The best way we can engage with America and have any hope of a policy change in the region is to have a strong, democratic, and independent state. This is not to say that this state should become an American outpost for American interests. Rather, any future Lebanese state needs to have solely Lebanon’s interests at heart when conducting foreign policy.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW.