Freedom of expression is the last frontier of any republic. Once it falls, the rest — the constitution, the judiciary, even sovereignty itself — become ornamental words. In Lebanon, that frontier is crumbling under the weight of hypocrisy. This morning, I was informed that my collaboration with Nidaa al-Watan daily, published by Michel al-Murr, had come to an end. The decision followed the newspaper’s decision to suppress a column I had written criticizing the presidency and the army command for their complacency toward Hezbollah, and for the symbolism of the now-iconic “Rock of Raouché.”

The article was not inflammatory; it was factual, grounded, and written in the spirit of civic accountability. But facts have become dangerous in a system that feeds on illusion. Behind the polite phrasing and editorial euphemisms lay the reality of a phone call — one of those discreet interventions that still govern much of Lebanese public life. And like so many before them, the editors complied.

The irony is that Nidaa al-Watan was never part of the camp of Hezbollah’s cheerleaders or the regime’s media arm.

It was supposed to be different — a platform that spoke for those who champion sovereignty, freedom, and alignment with the liberal West. Yet this episode reveals the fragility of that claim.

One cannot preach sovereignty while practicing subservience. One cannot quote the French Revolution while censoring a paragraph that questions authority. The West that these circles so eagerly appeal to — the one they invoke in every donor meeting and conference on reform — was built on the inviolability of free speech, the sanctity of dissent, and the courage to offend power.

To censor is not merely to silence a writer; it is to betray the very liberal values that the sovereigntist camp claims to embody. Worse still, it is to reproduce the authoritarian reflexes of the forces they oppose — to imitate the culture of intimidation they pretend to resist.

Lebanese history is filled with moments when intellectual independence was punished — first through silencing, then through slander. Today, political assassination has often given way to character assassination, but the intent is the same: to delegitimize the independent voice. When the pen becomes too sharp, the system — whatever its colors — moves to dull it, by exclusion, by discrediting, or by fear.

This is how mediocrity survives. It thrives on consensus, not conviction; on polite restraint, not moral clarity. Every time a journalist is told to “tone it down,” every time a paper kills a story to preserve a friendship, Lebanon’s democratic experiment dies a little more.

Lebanon’s crisis is not only economic or institutional — it is existential. We have replaced courage with caution, and ethics with expediency. Those who claim to speak for the Republic act as though sovereignty is a slogan, not a responsibility. And when faced with the test of principle, they fold — because principle, unlike politics, cannot be negotiated.

To defend freedom of expression in Lebanon today is not an act of vanity; it is a matter of national survival. For a country that loses its voice will soon lose its soul.

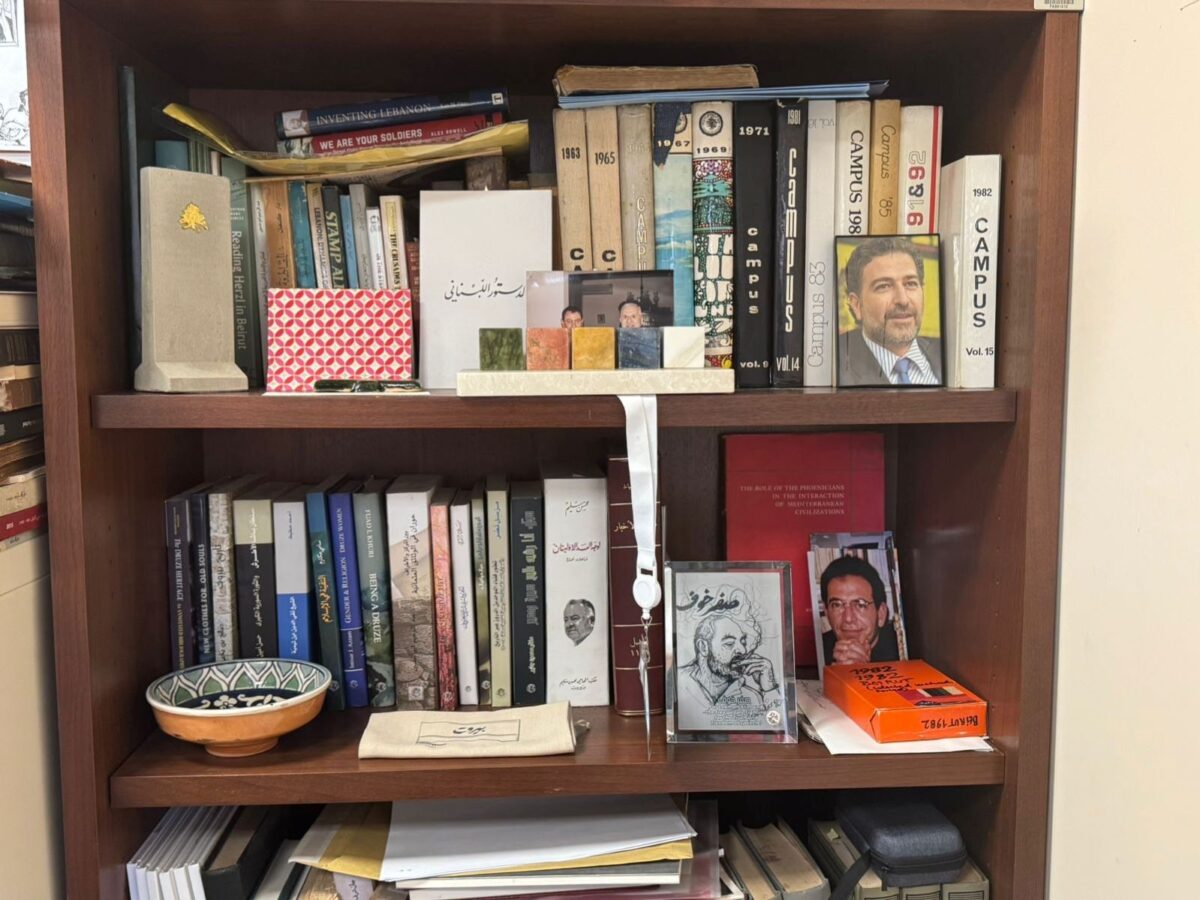

In my university office, above the shelves of books on Lebanon’s long struggle with power, hang the photographs of two friends — Lokman Slim and Samir Kassir — both assassinated for refusing to conform. Their memory is a constant reminder that freedom is not a posture but a calling, one that demands the refusal to yield, even when it costs you the comfort of belonging.

Those who choose silence in the name of pragmatism should know this: censorship is not a neutral act. It is complicity — the quiet continuation of oppression by genteel means.

Lebanon does not need more editors who fear phone calls; it needs men and women who understand that journalism without freedom is clerical work for tyrants.

Fear protects no one… and freedom alone befits Lebanon.

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah