The day the weapon spoke to the nation marked the moment “resistance” turned inward.

In the shifting geopolitics of the Middle East, the most destabilizing force in Lebanon today is not an external adversary but an internal armament whose purpose has long outlived its relevance. What was once framed as “resistance” has calcified into a self-defeating logic of armed autonomy that erodes state sovereignty and confines an entire people to the margins of political agency.

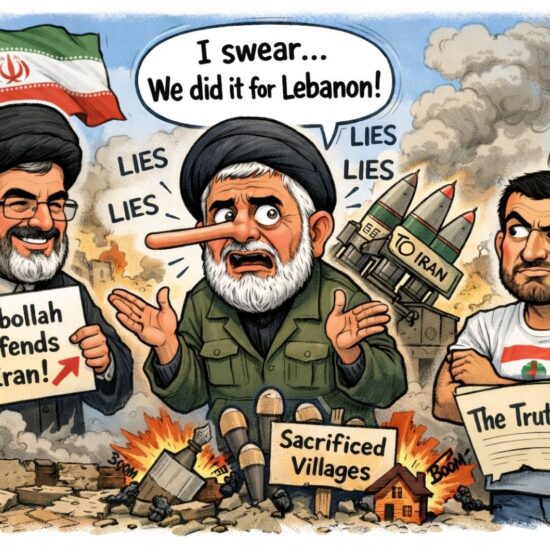

The controversy over Hezbollah’s arsenal, particularly outside the jurisdiction of the Lebanese state, has moved from political debate to a defining national crisis. The Lebanese government’s recent push to bring all weapons under state control reveals a struggle for political legitimacy as much as territorial integrity. Senior figures aligned with Hezbollah have openly resisted such efforts, framing disarmament as foreign imposition rather than a necessary assertion of national sovereignty.

This conflict is not merely procedural. It strikes at the core question facing Lebanon: who decides Lebanon’s fate? its citizens through constitutional institutions, or armed actors linked to external power centers? When dissent is met not with political argument but with intimidation, the narrative of resistance collapses into coercion. Weapons aimed inward, against citizens demanding accountability and reform, cease to function as deterrence and instead operate as instruments of political intimidation.

That rupture became unmistakably explicit in Naim Qassem’s latest remarks, which crossed from political rhetoric into outright menace. In a public statement, he threatened Lebanese citizens with killing and abduction, warning that any attempt to place weapons under state authority would provoke consequences beyond society’s capacity to endure. He went further, declaring, without ambiguity, that the question of restricting arms would not end unless Lebanon itself came to an end.

This statement must also be read in the broader Iranian strategic context. Iran has made clear that it will never leave Lebanon, regardless of cost, and remains committed to its military disengagement from Israel, a point Qassem has reiterated previously. Yet Tehran is equally committed to maintaining influence along the eastern Mediterranean coast and securing a position in the emerging regional order. The recent visit of Abbas Araghchi to Beirut carried this underlying message, even through flexible public language. Qassem’s high-toned rhetoric reinforced the impression that any disengagement from Israel via concessions in southern Litani would not equate to a withdrawal of Iranian influence from Lebanon. His speech was interpreted as full defiance against disarmament, coupled with the threat of confrontation: “not a stone will remain unturned”, in line with the principle “mine and my enemies, O Lord”. He emphasized that the weapons plan is indivisible, with no second phase, and in raising threats to the maximum, employed unusual expressions like “beyond what you can bear,” implicitly directed at the Lebanese authorities, who acted as if they did not hear the warning. This was not rhetoric. It was a declaration of doctrine: the organization’s survival takes priority over the state. At that point, arms are no longer tools of defense or leverage, but instruments of coercion against society, institutions, and the very idea of citizenship.

By linking disarmament to national extinction, this framing represents internal escalation insofar as it treats state sovereignty itself as negotiable under threat, rather than as a non-derogable national principle.

The implications extend beyond Lebanon’s borders. Hezbollah remains structurally and strategically embedded within Iran’s regional architecture at a moment when Tehran is under unprecedented internal strain. Iran’s leadership faces deep domestic unrest, economic exhaustion, and growing legitimacy deficits at home, even as it seeks to preserve leverage through proxy networks abroad. This convergence of internal pressure and external entrenchment increases the risk that Lebanon becomes less a sovereign actor and more a pressure valve for regional recalibration.

International dynamics further complicate the picture. Western and regional powers continue to press Beirut to consolidate authority and assert a monopoly over force, while Israel maintains upper hand controlling any movement for Hezbollah and its operatives across the Lebanese territory. Lebanon is thus suspended between the necessity of reclaiming sovereign decision-making and the danger of becoming the arena in which regional tensions are discharged.

The deeper crisis is conceptual. The contradiction between resistance rhetoric and the requirements of statehood has become impossible to ignore. Sovereignty is not measured by the volume of weapons outside state control, but by the capacity of institutions to function without coercion. When arms undermine economic recovery, international engagement, and the social contract itself, they no longer shield the nation, they weigh it down.

Lebanese society understands this intuitively. A generation shaped by economic collapse, political paralysis, and repeated crises cannot afford another cycle of conflict driven by agendas it does not choose. What is being demanded is not vulnerability, but normalcy: a functioning state where citizens can assert their decisions and protect their future.

True resistance today is not the preservation of an armed faction above the law. It is the collective insistence that Lebanon’s future be decided within Beirut’s constitutional framework, not imposed by force or dictated from abroad. A country that cannot own its decisions cannot protect its people.

Lebanon may not collapse all at once. It will erode incrementally: a law hollowed out, a minister intimidated, a dissenter silenced, an investor deterred, a young citizen forced to leave. And when the reckoning comes, it will be clear that the weapon said to protect the nation was in fact the instrument that hollowed it from within.

Lebanon stands at a crossroads. One path leads toward institutional sovereignty and collective recovery. The other preserves armed dominance at the cost of national survival. History suggests that nations rarely survive the latter choice.

Elissa E Hachem is a journalist and political writer specializing in regional affairs and governance. Former Regional Media Advisor at the U.S. State Department’s Arabic Regional Media Hub, with broad experience in strategic communication across government and private sectors.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW