Not everyone who dismantles nationalism, exposes the fraud of “total liberation,” or rejects the militarization of society in the name of grievance automatically becomes the “Arab Fukuyama.”, assuming that referring Francis Yoshihiro Fukuyama an American political scientist and author of the book The End of History and the Last Man as a negative label. This label is not analysis—it is evasion. It is what intellectually exhausted writers do when they no longer wish to argue, only to dismiss.

Reducing Hazem Saghieh to a prefab Western caricature is not a critique; it is a shortcut. It allows the writer to avoid engaging with what Saghieh actually says, and instead attack what is convenient to imagine.

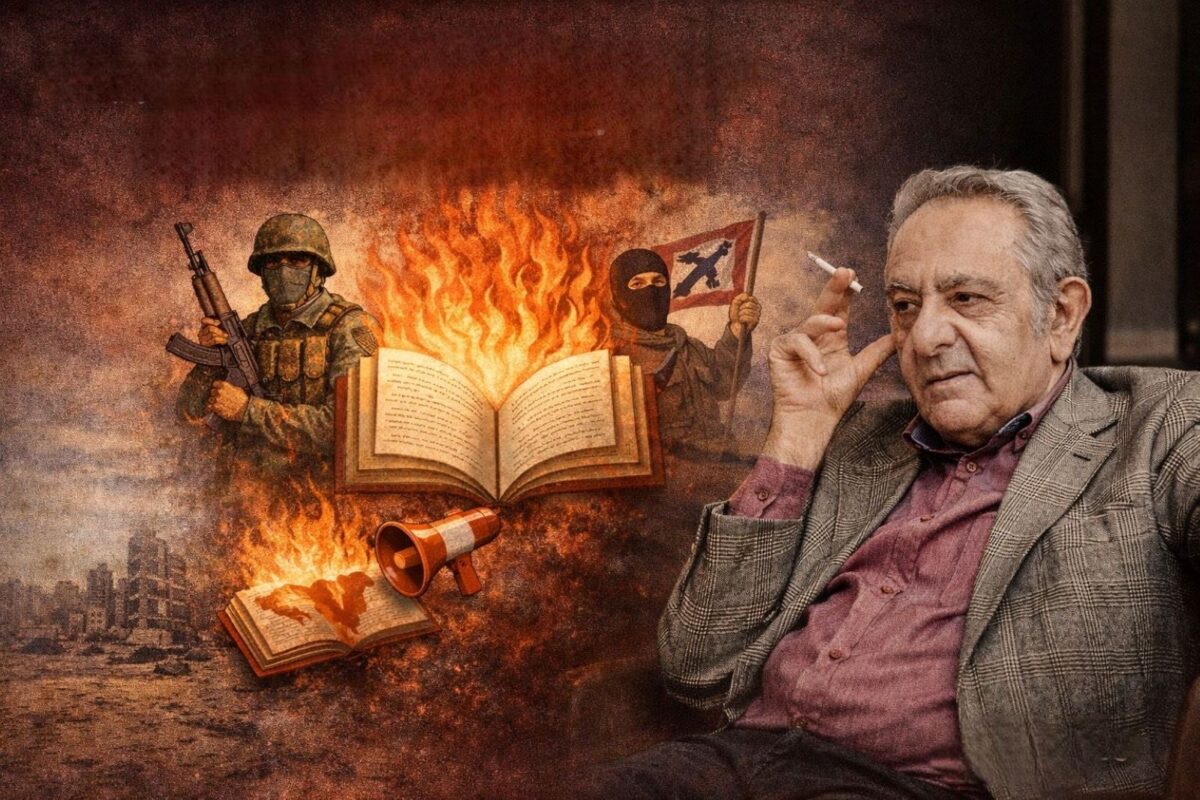

Saghieh has never declared the “end of history.” He has never proposed liberalism as destiny, nor presented a universal script for salvation. His project—since his earliest break with Arabist orthodoxy—has been far more unsettling: exposing how identity becomes weaponized, how states mutate into security estates, and how societies are converted into permanent reservoirs of expendable lives.

The difference between Saghieh and Fukuyama is not semantic. It is foundational. Fukuyama wrote about the exhaustion of global ideological conflict. Saghieh begins from a harsher premise: that our region never truly entered politics at all. It lived instead inside regimes that suspended rights in the name of the nation, normalized repression under the banner of “the larger cause,” and converted emergency into a permanent condition.

Confusing these two is not innocent. It is convenient.

What the attack also deliberately confuses is the difference between populist frontism and principled opposition to armed authoritarianism. Saghieh’s rejection of the Syrian regime, militia economies, and the mythology of “eternal resistance” is not tribal alignment. It belongs to a liberal tradition that understands a simple truth: whoever monopolizes violence and truth inevitably destroys politics.

Being against a repressive regime does not mean you are waging an existential war. Rejecting the militarization of society does not mean denying history or geography. Calling for disarmament does not make you a “reverse resistance ideologue.” These are clever metaphors—and empty ones.

When Saghieh critiques the “culture of force,” he is not proposing a military doctrine. He is exposing a value system that equates dignity with guns, politics with violence, and belonging with war. Reading this as a theory of national defense is either intellectual incompetence or deliberate falsification.

And this is the idea that terrifies his critics:

An armed society is not a strong society.

It is a society that has failed to invent politics.

That is what they cannot afford to confront.

But the most revealing part of this attack is not what it says—it is where it appears. These critiques were published on platforms that have never defended freedoms, never centered civilians, and never held power to account. Their record is not one of critique, but of alignment—with regimes and projects that transformed death into a rhetorical resource.

Platform choice is not neutral. It is part of the argument.

When a liberal critic is attacked from outlets that never condemned mass slaughter in Syria, never opposed the commodification of death in Lebanon, and never challenged the transformation of societies into open killing fields, this is not coincidence. It is structural coherence.

When opposing authoritarianism becomes “bias,” while justifying it becomes “realism,” the problem is not Saghieh—it is the moral collapse of the critic. When the call for a civil state is framed as “foreign obedience,” while militias are rebranded as “historical movements,” we are not witnessing debate. We are witnessing epistemic decay.

This attack reveals nothing about Saghieh. It reveals everything about its author: the narrowness of his intellectual world, his dependence on an audience that does not question, and his need for platforms that reward alignment rather than evidence.

Saghieh is accused of serving grand agendas, of being part of civilizational projects, of advancing Western conspiracies—without a single argument, citation, or proof. This is not refutation. It is insinuation.

Worse, the text reproduces exactly what it pretends to oppose: it divides the world into camps, assumes hidden intentions, turns ideas into conspiracies, and refuses to interrogate internal responsibility.

This is not critique. It is doctrine.

The real problem with Saghieh is not intellectual—it is existential. He does not provide enemies that are comfortable, narratives that cleanse, or myths that redeem.

He refuses to absolve “the nation.”

He refuses to sanctify the sect.

He refuses to deify the gun.

In a political culture built on self-justification, this is heresy.

That is why he is attacked—not because he is wrong, but because he violates the golden rule of Arab political discourse: never ask what society does to itself. Only ask what “the other” does to it.

And that is precisely why he matters.

This article originally appeared in Elaf

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah