Like the parable of the drowning cleric, catastrophe rarely begins with sin. More often, it is born of arrogant miscalculation—wrapped in the language of faith.

A storm once struck a small town, and torrential rain caused a devastating flood. A cleric stood on the steps of a mosque, hands raised in prayer, convinced that divine providence would intervene at the right moment. A neighbor passed by in a small boat and warned him of the rising water, urging him to leave. He refused, certain that God would protect him. The danger escalated. More opportunities for rescue followed—clearer, safer, more urgent—but he remained where he was, persuaded that salvation could only arrive in the form he himself imagined. When he finally drowned, he did not attribute his fate to stubbornness, but regarded it as a test of faith.

This parable does not indict belief. It exposes the lethal confusion between trust and the suspension of reason, between faith and denial, between conviction and the refusal to assume responsibility.

At its core, it offers an uncomfortably accurate description of Lebanon’s present condition—particularly the way large segments of Hezbollah’s constituency interpret the relentless Israeli strikes and the predicament into which an entire community has been pushed by an unwavering commitment to a single option, regardless of its human and political cost.

What is presented today as “steadfastness” or “resilience” is, in reality, a systematic denial of reality. Israeli strikes are not a sudden anomaly, nor a newly hatched conspiracy, nor the result of a misunderstanding that slogans can correct. They are the direct outcome of a long-standing refusal to acknowledge a basic truth: a weapon outside the authority of the state is no longer a source of strength, but an existential burden on those it claims to protect.

Every call for restraint, every warning against open-ended confrontation, every serious proposal to place arms under state authority and restore sovereignty has been met with the same response: we know better; time is on our side; the axis will protect us.

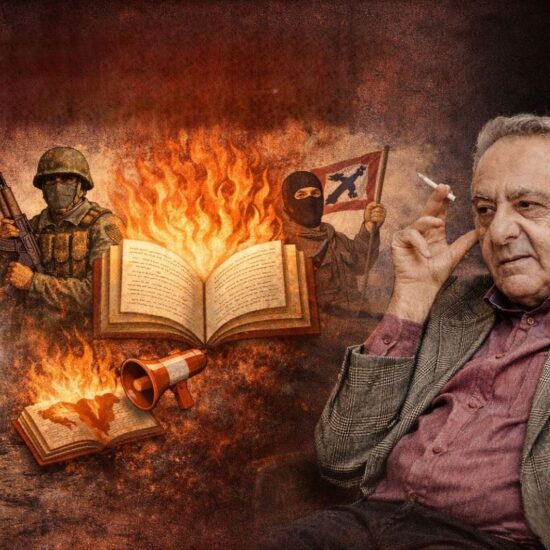

More dangerous than the weapon itself, however, is the fortification behind a closed and instrumentalized version of religion—one deployed not for moral guidance, but for justification; not to cultivate ethics or discipline behavior, but to silence debate. Blind faith, once transformed into a political creed, does not shield a community. It isolates it. It deprives it of the capacity to hear warnings, even when those warnings come from within the nation itself.

The belief that our version of religion alone guarantees salvation, while dismissing the voices of Lebanese who see the persistence of arms as collective suicide, is not an expression of piety or resolve. It is a total rupture with reality—and with the logic of responsibility.

No religion grants immunity from consequences. Faith does not absolve choices of their outcomes. A belief system that expels reason and demonizes anyone who warns of impending disaster does not lead to redemption; it rationalizes destruction.

Here, the parable intersects painfully with Lebanon’s reality. Hezbollah’s supporters who treat the weapon as a divine fate rather than a political choice subject to debate are repeating the drowning cleric’s error. They reject the boat because they recognize only the salvation they believe in—not the salvation imposed by reality.

And yet, the boat still exists.

The Lebanese state—despite its weakness, corruption, and dysfunction—remains the only framework that can, in theory and in practice, protect the population. Not through adventure, but through responsibility; not through slogans, but through legitimacy. Disarmament is not abandonment. It is a last attempt to rescue a community from permanent attrition.

But this boat has been deliberately disfigured—branded as betrayal, much like the first boat in the parable was rejected because it did not descend from the heavens.

What deepens this tragedy further is that this obstinacy has little to do with Lebanon itself. It is increasingly a wager on a crumbling regional order. Betting on Iran today is no longer a sign of strategic loyalty or “resistance,” but an exposed gamble on a besieged, overstretched regime compelled to export its crises rather than resolve them.

Binding the fate of an entire Lebanese community to this wager has nothing to do with faith. It is the insistence on remaining atop the minaret while the water engulfs everything below.

The voices of Lebanese who view the weapon as an existential threat—to Shiites no less than to other citizens—are not voices of weakness or treason. They are last attempts to halt the descent. Silencing them in the name of doctrine does not dignify the tragedy; it strips it of any ethical meaning.

When political debate is replaced by religious verdicts, and reason is criminalized in the name of belief, society becomes captive not only to an external enemy, but to an internal logic that insists on marching toward the abyss while proclaiming salvation.

In the drowning cleric’s story, the problem was not insufficient faith, but the refusal to accept rescue when it was offered. This is Lebanon’s reality today. The boats have arrived. The warnings have been issued. The flood is no longer metaphorical.

Those who insist on drowning have no right to drag others with them—in the name of God, resistance, or any other narrative that has long since exhausted its meaning.

Hezbollah’s insistence on clinging to the weapon as salvation while the ship is already sinking is no different from trying to purchase a ticket on the Titanic after it has struck the iceberg. No amount of good intentions or loud slogans can change the fact that the problem is no longer the destination—but the ship itself

This article originally appeared in Elaf

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah