Let us, for the sake of this short article, put aside the ambassadors of the East. Those dispatched from the imaginary anti-imperialist axis stretching vaguely between Tehran and Pyongyang.

These figures are not diplomats in any meaningful sense. They are emissaries for regimes that confuse intimidation with statecraft and monologue with diplomacy. Their role is largely ornamental: flags, receptions, protocol; while the real work is conducted elsewhere, usually by masked men with guns.

They are not the subject here.

The subject is a wave of Western diplomats, particularly some American and many European ones; who arrived in Lebanon over the past decade with confidence, credentials, and, above all, a vocabulary. They were welcomed with cautious hope. At last, many thought, here are people who might understand what this country is going through.

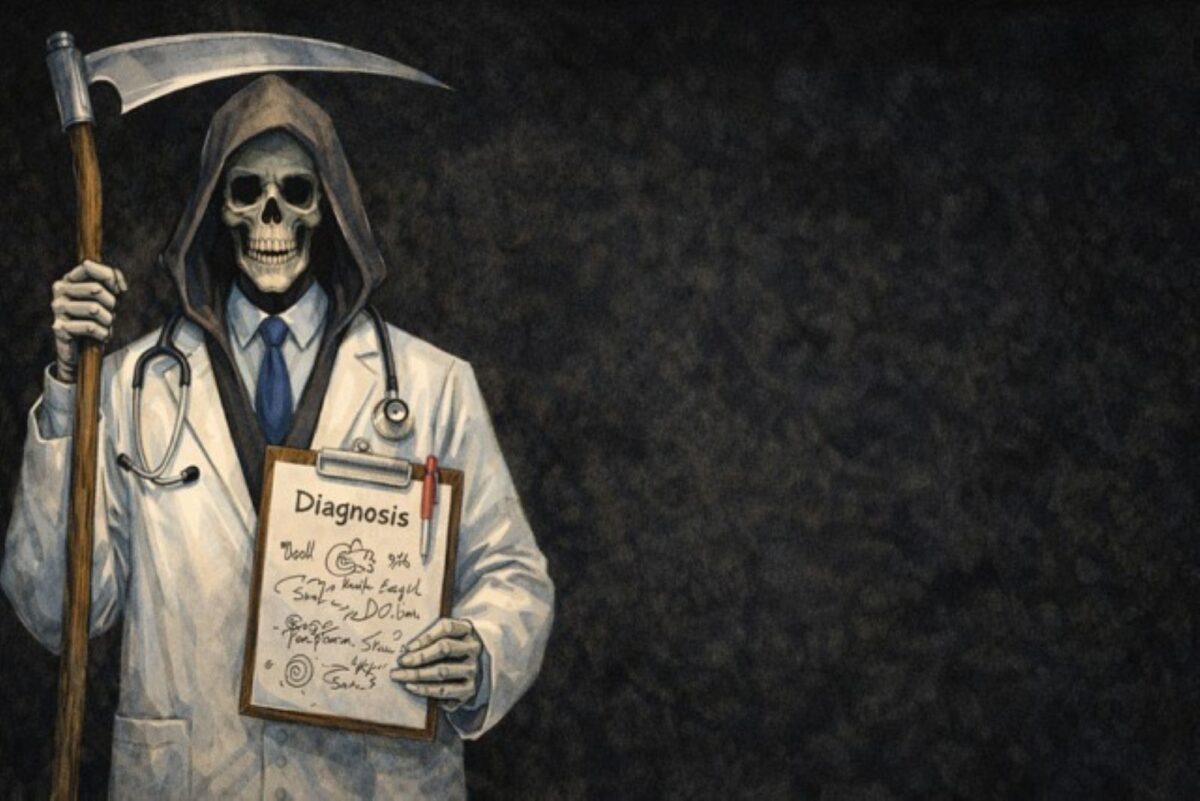

What followed was not understanding, but pompous diagnosis, and a very specific kind of it.

It was a long, heavy period during which some of the worst assaults against the Republic and the largest portion of its people were carried out: foreign hyt, illegal militias, armed subversion, assassinations, organized terror, institutional erosion, economic strangulation, political paralysis. And throughout it, Western diplomats displayed remarkable diagnostic certainty.

The problem, they insisted, lay with the patient.

The vocabulary was limited and endlessly recycled. Corruption. Sectarianism. Accountability. Epstein hadn’t emerged yet. This became the standard explanatory kit, deployed with the confidence of medicine practiced safely away from the patient.

Iran rarely entered the picture. Hezbollah was treated delicately, as a “component.” Armed proxy gangs were softened into “actors.” Responsibility was always local, and when that proved inconveniently broad, it was refined.

The Lebanese. And more precisely, the Christians. Or, for academic polish, “right-wing Christians.” To be joined later by “oil-rich Muslims,” once redistribution of moral blame became a natural exercise.

Only certain groups were ever allowed agency; and therefore blame. Those attached to the idea of a sovereign Republic, a Constitution, or the simple fear of becoming Syria yesterday or Iran today were swiftly categorized. Isolationist. Imperialist. Zionist. Fascist. Racist.

Lebanese identity itself was quietly recoded as inherited privilege.

Sovereignty became a psychological disorder. Self-defense became intolerance. This was not mere hypocrisy. It was something more clinical.

It was hypocrisy: the reduction of democratic principles into performative ritual, stripped of meaning and consequence. Democracy invoked as vocabulary, not defended as structure. Values recited, but never enforced.

A politics of posture where empathy replaced clarity and explanation substituted for judgment. Terror was contextualized. Citizenry was scrutinized.

I once found myself at a dinner hosted by a Shia friend, openly opposed to Hezbollah, alongside a couple of European ambassadors. A sufficiently progressive sampling of diplomatic Europe.

As tends to happen in Lebanon, the conversation drifted toward Iran and Hezbollah. I explained, calmly, why such groups cannot be treated as normal political parties or benign social “components,” but are in fact authoritarian gangs that borrow the language of politics to conceal coercion.

One diplomat objected. With confidence. “But don’t you want to live with your friend, the host?” The question was meant to be moral. It was merely revealing.

Opposing an armed, foreign-owned organization, illegal, authoritarian, racist, and criminal, was equated with rejecting an entire community. A political argument collapsed into a social accusation. The gang became the minority. The gangsters became its people. This confusion was not accidental. It was ideological. It allowed one to appear tolerant while excusing terror.

My reply ended the exchange. “Would you have asked the same,” I said, “if I were describing the Nazi Party and my friend here happened to be German?”

She found another conversation immediately thereafter.

During that same period, an ecosystem of NGOs flourished, dedicated to explaining Lebanon to itself. Woke abstractions replaced political analysis. Terror apologia was rebranded as understanding. Armed politics acquired moral depth. Sovereignty became suspicious. Violence was contextualized until it dissolved into anecdotes.

Thus the mullahs of Iran, the fanatics of Hezbollah, their Sunni equals, self-declared liberators of Palestine, and passing anarchists were cast as misunderstood protagonists. The rest were reduced to privileged obstacles.

The damage done by Obama, Obama 2.0, Sarkozy, Macron, and this generation of Western diplomats was not accidental, nor was it neutral. It was ideological. By confusing intruders with communities, fanaticism with legitimacy, and sovereignty with privilege, they hollowed out the very Republic they claimed to support.

The diplomats of the axis never pretended to care about our Republic. The Western ones did. That is why the damage they caused was less visible, and may ultimately prove far greater.

Lebanon did not collapse because it failed Western ideals. It collapsed because, when those ideals were tested by external forces with armed subversion, Western ideals failed Lebanon.

A Foreign Affairs minister like Joe Raggi, a negotiator like Simon Karam, and a US ambassador like Michel Issa should be able to sanitize diplomacy. To pull it back from Western reluctance and Eastern brutality, and restore clarity where vocabulary once stood in its place.

Republics cannot survive on words alone.

Eli Khoury is the publisher of NOW and is a co-founder of the Lebanon Renaissance Foundation. He is on Twitter @eli_khoury.