The maritime border with Israel was the first thing Lebanese Prime-Minister Najib Mikati tackled with President Michel Aoun after his government was finally formed in September. It came even before the new government even had time to talk about the dire fuel crisis the country is facing.

Halliburton had announced it was hired to start drilling in the maritime area disputed by Lebanon, and Beirut complained to the UN about it. One day, and the whole matter was put to rest in Lebanon.

The negotiations on the maritime border with Israel seem to make headlines once in a while, but they may also be doomed to remain one of the forever unsolvable issues between Israel and Lebanon.

The truth is that, beyond all the efforts some diplomats may be willing to make and beyond the shuttle diplomacy by various US envoys, no one really means business in this matter. At least not for the moment and not until a game changing event that cancels the stalemate happens in the region or locally.

The US mediator for the indirect talks on the border demarcation Amos Hochstein was in Beirut on Tuesday and Wednesday to discuss the maritime border file with various Lebanese politicians before heading to Israel and Egypt. On Thursday, in an interview with Al Hadath, he said that if a deal takes too long, it doesn’t happen.

“I think that in these kinds of efforts what we’ve learned is that if you take a lot of time, it doesn’t happen,” he said. “So we need to be focused, and we need to move quickly.”

“Perhaps there should be some shuttle diplomacy first, in order to assess the positions of the parties to identify where there is room for negotiation and then ultimately, to go back to Naqoura and complete the negotiations,” he added.

But there is no moving quickly. Deals happen when the parties are really interested in making things happen. And, in this case, neither Israel, nor Lebanon are convinced that this is the way to settle the matter, nor that it should be in any way prioritized.

An inherited problem

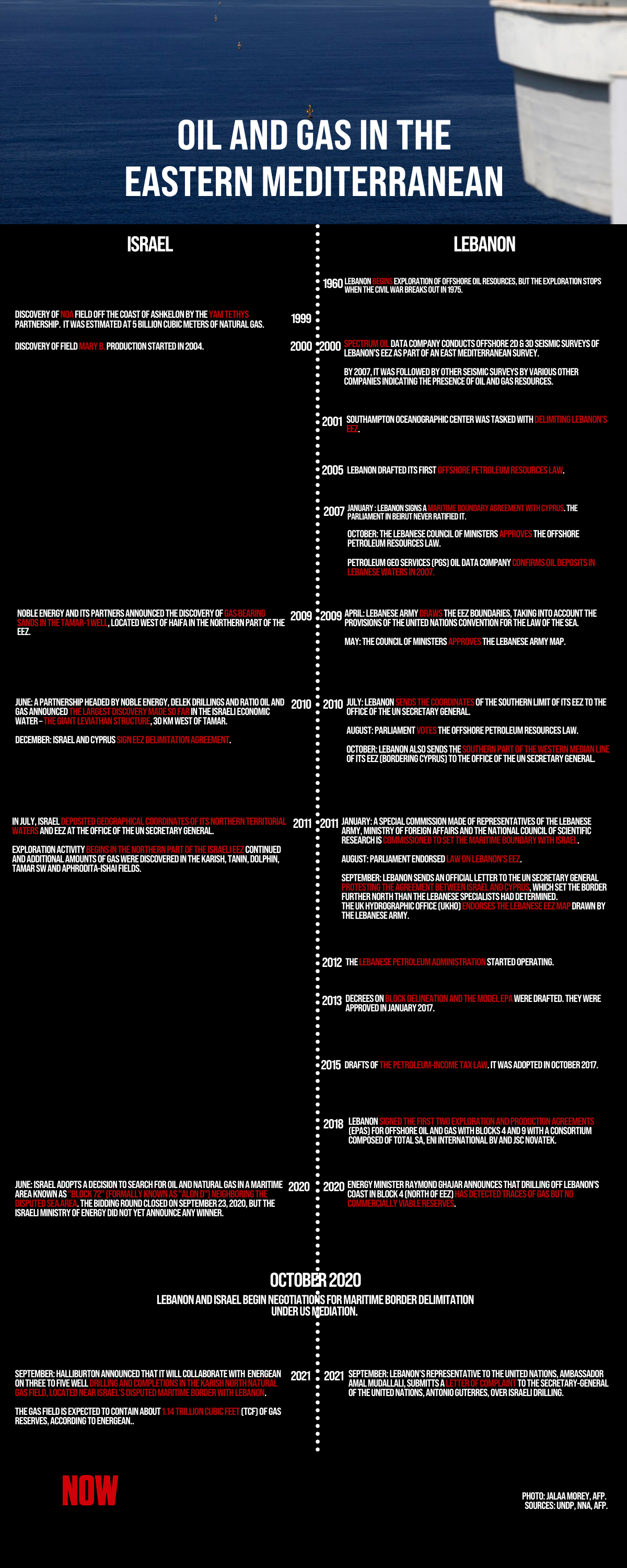

The talks started in October 2020, one year ago, as a last effort by Donald Trump’s administration to score some foreign policy points – not many, but still. The fact that Lebanon agreed to sit for the negotiations, even indirectly, was indeed something, they must have thought.

But back then, Lebanon was at a different stage. The electricity system was still providing a few hours of power per day and the fuel crisis hadn’t begun yet. Although it was clear that the Lebanese powerplants would end up shutting down within months, there was no real alternative solution, and the gas in the Mediterranean seemed a farfetched, but at least somewhat possible, solution.

Everyone knew it was going to take long and the process was going to be stalled by all sorts of deadlocks, even with Hezbollah staying out of the matter.

The talks hit a bump in May, when Lebanon refused to negotiate on the map used by the UN. The Lebanese delegation said the demarcation line extended much further south. The disputed area was of 860 square kilometers in the documentation of the UN and Israel. Lebanon wanted 2,300 square kilometers, which include at least part of the Karish North field, where Israel had already found gas in April 2019.

The Lebanese officials disagreed that there was any increase in their demands. Israel rejected the claims. That was the end of it.

Of course, in June, Israeli Energy Minister Karin Elharrar made that statement about getting creative. “Despite Israel’s strong legal case, we are willing to consider creative solutions to bring the matter to a close,” he said. But Lebanon is not really in the shape of getting creative. It needs help, it needs reforms, it’s facing collapse. Asking it to get creative was, if anything, a condescending, quite offensive remark.

Nothing really happened until September 14, when Halliburton announced it was awarded a contract by Energean to start drilling in an area disputed by Lebanon.

A day after the Mikati cabinet in Beirut was sworn in, all Lebanese politicians, including the PM and president Aoun, made outraged statements on the matter. Lebanon complained to the UN Secretary General. And, again, that was it. There isn’t much more Lebanon can do.

Nice to meet you, but…

In Lebanon, where the population is facing daily power cuts, lack of medicine, a crippling fuel crisis, and a quest for justice after the huge Beirut blast that has brought Hezbollah at loggerheads with the Lebanese Forces, Hochstein’s visit passed almost unnoticed. Even the usual critics who would have otherwise taken note that Biden’s envoy was born in Israel and also served in the Israeli army were not interested in making a fuss over it. They had bigger fish to fry locally.

On the Lebanese side, parliament speaker Nabih Berri told Al Shaq al Awsat on Thursday that his meeting with Hochstein was “more than positive”. A more than polite and diplomatic way of saying “sure, nice to meet you too”.

Judging by Berri’s interview, what occured during Hochstein’s visit was that the Lebanese side rejected the idea of shuttle negotiations suggested by the US instead of the indirect negotiations held at the UN base in Naqoura. In fact, he said, there was no real possibility of restarting the talks. No one was even considering it.

Israel has no interest in settling anything with Lebanon in this regard either. It already pumps gas from offshore fields and it doesn’t really see an obstacle in the fact that the border with Lebanon is not set in …paper.

Hochstein said resolving the border issue would help alleviate Lebanon’s power shortage by allowing it to develop its offshore gas resources. But that is quite far-fetched, since, due to the dispute, Lebanon hasn’t even had the chance to explore much.

For Lebanon, at the moment, a bird in the hand is more valuable. The biggest challenge is to keep the US committed to its promise to allow the country to import gas from Egypt and electricity from Jordan through Syria and temporarily and partially solve the much more stringent need for at least a few hours of electricity per day.

The birds in the bush – the great promise of oil and gas in the Mediterranean after settling the border with Israel – seem distant dreams of cornucopia that no one has time to dwell on right now. They are only brought up once in a while when in need of a political distraction.

Ana Maria Luca is the managing editor of @NOW_leb. She tweets @AnaMariaLuca79.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOW.