Marina Hamdan, 24, stumbled upon a book she had been looking for for ages while wandering around the Beirut International and Arab Book Fair. When she picked it up, she discovered the price was beyond her budget.

“A few years ago, $10 would have been fine for one book, but because of the crisis, I don’t indulge as much as before,” Hamdan told NOW.

Since pre-covid 19 days, Hamdan has looked forward to the annual book fair, which is one of the most important cultural events in the crisis-riddled country.

The last edition was held from March 3rd to March 13th for a special 10-day run, its original date is usually early December. Furthermore, the March edition lacked the original number of participants as a result of agreements with other book fairs for the purpose of generating more foreign currency revenue.

“The March edition was nice, but we were missing a little diversity,” Hamdan said. “The crisis definitely affects our purchasing power, which dampens the experience, but I’m glad to see the book fair back.”

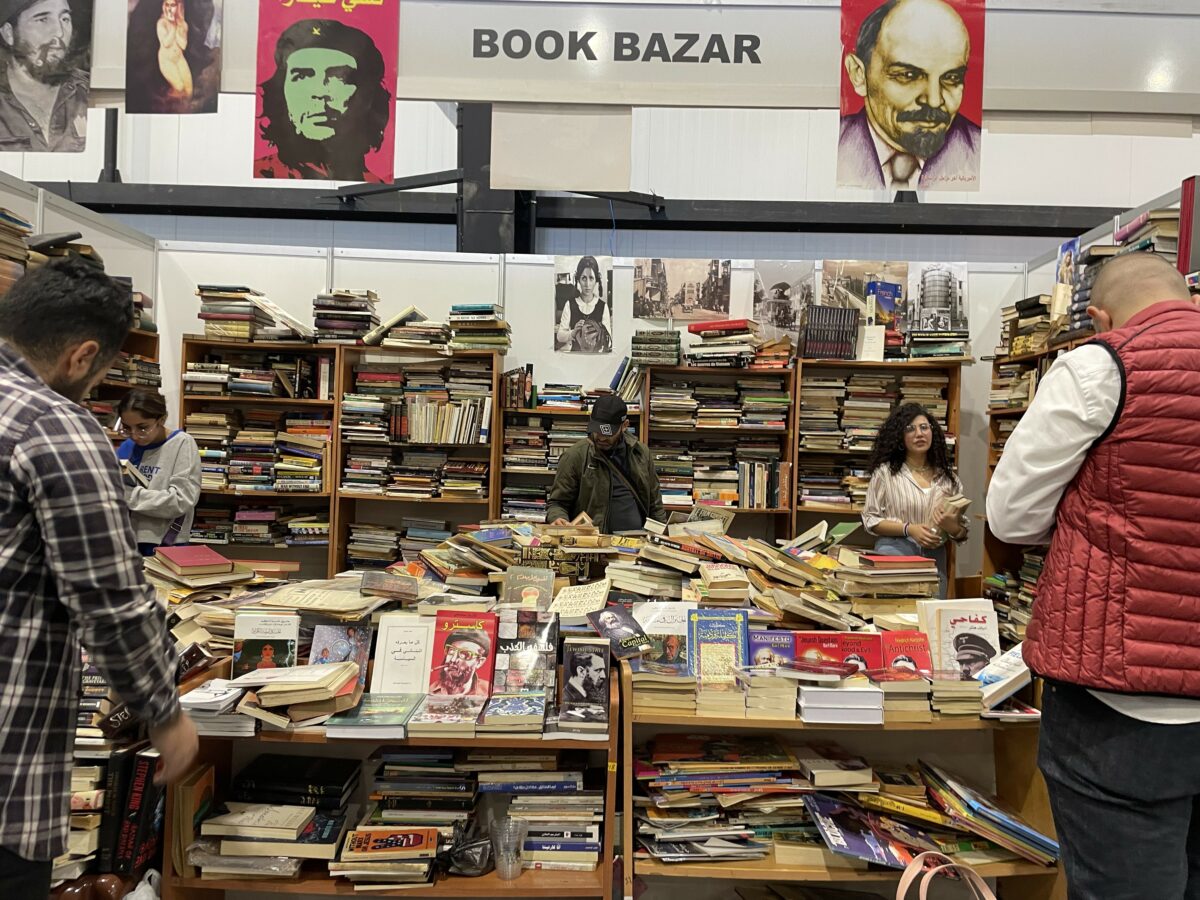

Each year since 1956, Beirut has held the Arab Book Fair. First held in the West Hall of the American University of Beirut, the Book Fair has become a major event in the city. Established in the mid-1950s, it was the first event of its kind to take place in the region, with books covering a wide range of subjects: politics, children’s books, novels, etc. But the economic collapse that has paralyzed the country since 2019 has significantly changed the experience of publishers and book lovers, who must resort to novel budgeting tactics to meet halfway on the prices.

The come-back

According to the fair’s spokesperson, Akram Hamdan, the March fair was simply a statement that Beirut’s cultural life had been revitalized.

Now back on its original December dates, it is still too early to tell how many attendees there will be since the fair started on December 3rd and runs for 12 days. Space, however, is one of the major obstacles faced by the organizers.

Due to the August 4 explosion in 2020, the fair’s original setting was destroyed. Consequently, they downsized, reducing their capacity to accommodate publishing houses by more than half, from 10,000 square meters to 4,000 square meters in size and from 200 publishers to barely 90.

But perhaps not all is lost. “What startled me was the presence of youngsters who would not only attend but buy in bulks,” Hamdan said. “This is a positive indicator that the purchasing power, although decreased, was not eradicated completely.”

The economic collapse that has paralyzed the country since 2019 has significantly changed the experience of publishers and book lovers, who must resort to novel budgeting tactics to meet halfway on the prices.

Lana Halabi, director of Halabi Bookshop, said the clientele has remained consistent over the years, comprising of a diverse crowd – youngsters, seniors, and even kids. People are, however, gravitating towards used books more often.

“We are fortunate to be able to provide used books as an alternative to people. For new books, we must stick to the daily lira rate since most publishing houses price them in dollars,” Halabi told NOW.

Halabi offers children’s books for as little as 20,000 L.L and 80,000 L.L, which amount to less than $1 and $2. According to the director, self-help books are in higher demand this year than other years, and although their client base has remained consistent, books starting at $10 and above are now less in demand.

In October, the Blom Lebanon Purchasing Managers’ Index rose to 49.1 from a four-month low of 48.8 in September. Readings above 50 indicate growth, while readings below 50 indicate contraction. According to the Central Administration of Statistics’ Consumer Price Index, Lebanon registered its 26th consecutive month of triple-digit inflation in August as the local currency continues to deteriorate against the US dollar in the parallel market.

Between the positives and the negatives

According to Hussein Kaouk, an employee at a French publishing house at the fair for the very first time and a habitual participant, there is a perception of class differences among customers.

At French book fairs in Lebanon, students from private French schools are usually more financially comfortable than public school students, who can barely afford basic necessities,” Kaouk explained to NOW.

According to Kaouk, publishing houses and bookshops that target children usually rely on schools to bring their students. However, schools haven’t shown up as expected this year.

“As a result of the crisis, we didn’t expect much profit, and in reality, we barely cover our expenses, but the presence of English and French books nonetheless highlights Lebanon’s cultural diversity and attracts more customers,” said Kaouk.

Beirut’s role as a cultural center has diminished in recent years. Literary and book reading events, however, show that, despite the challenges, Lebanese still seek knowledge and escape through literature.

In addition to being limited in space and unable to display more expensive items, he said the store’s profits were severely affected.

As avid visitors of the book fair from a young age, Lara Othman, 33, and her sister Maria, 45, have saved up for the event for the entire year.

“It is hard to predict how much money we will be able to spend since this year we didn’t make as much as the previous year. We used to love to splurge on books” Othman told NOW.

“Despite our love of literature, the problem is shared by many of our friends, so we just have to figure out how to make the necessary changes and compromise for the sake of our love for books,” she added.

As a result of the economic crisis, political instability, and COVID-19 pandemic, Beirut’s role as a cultural center has diminished in recent years. Literary and book reading events, however, show that, despite the challenges, Lebanese still seek knowledge and escape through literature.

Dana Hourany is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. She is on Instagram @danahourany and Twitter @danahourany.