The golden age of Beirut’s cinemas hidden in a basement

Abboudi Abu Jaoude prefers to speak in Arabic: due to the need for precision, the concern of someone who speaks about love and must do so with accuracy. He had time to calibrate the terms of his collection, the reasons for his debut, the stubborn survival of fifteen years of conflict, and more than thirty of demographic, economic and cultural crisis in post-war Lebanon: the time to temper the very bitter knowledge of a life that is no longer – if not in a closet, or, at most, boxed up. It is the golden age of Lebanese cinemas, the grassroots testimony of a lively and synergistic thirty years in which Lebanon hosted three hundred cinemas and theatres, and curious people from all over the world looked out onto the gulf of Beirut to see that indeed, it was truly, this city that today you would say unrecognizable, the Paris of the Middle East.

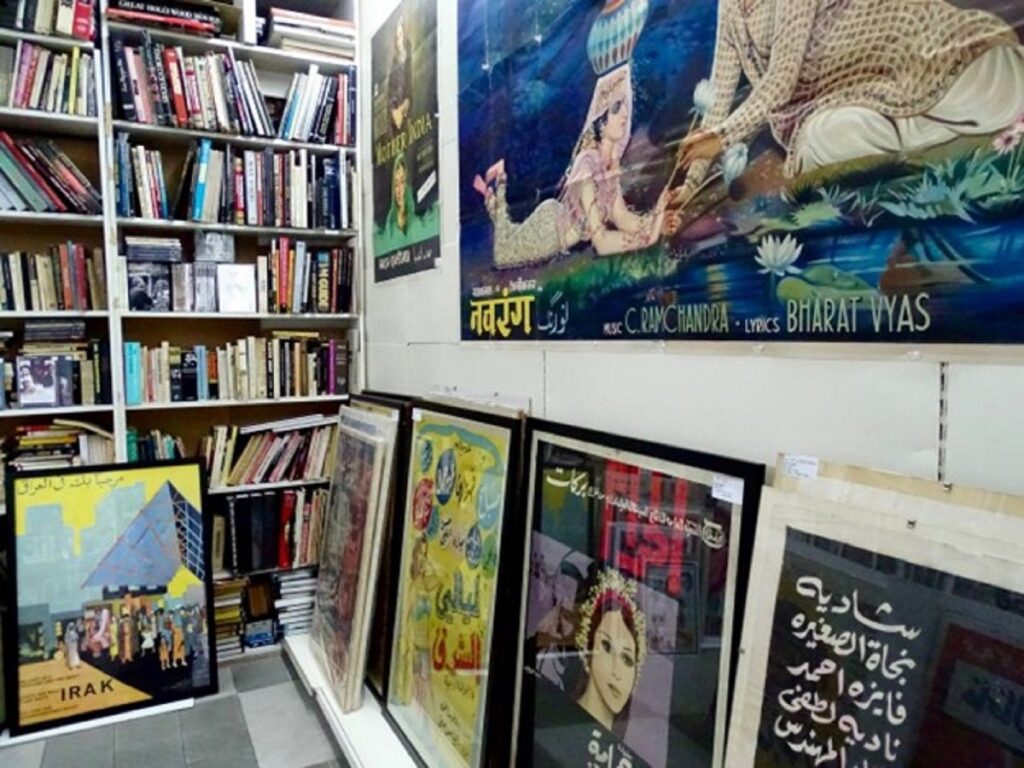

Part of Abboudi’s collection in his shop in Hamra. Photo credit: Valeria Rando

Abboudi speaks surrounded by the stacks of posters, books, photographs, cassettes, vinyls and CDs that crowd the basement of an anonymous building in Hamra, his island of peace and time capsule, while the unfolding of the pages, the printing paper heavy of bright colors and large letters, makes room for the cup of Turkish coffee which, with the hospitality of someone who opens the doors of his home, he kindly hands to his customers.

“The beginning of this story is that of a banal youthful love for cinema, a dispassionate and enchanted love of the kids of my generation for the world in which they happened to be born, and of which we didn’t realize the exceptionality,” he confesses with modesty: almost as if it had been natural for him to embark on the path of collecting. A non-choice. The inertial motion of those who, in contemplating the extraordinary, are absorbed by it: and, of which, they soon become part. When I ask him if he is proud of his work today, he immediately corrects me: “no, it’s not a job. It’s my joy, my hobby.”

Part of Abboudi’s collection in his shop in Hamra. Photo credit: Valeria Rando

In sixty years of joy, not work, he has collected approximately 20,000 cinema posters, 2,500 Americans, 1,000 Italians, 500 French, another 300 English, and more than 400 Lebanese – his favorite ones -, 150 Syrians, 50 Iraqis, 200 Moroccans and Algerians, and more than 600 Indians. And just as youthful memories hold firmly to the memory of the first kiss, so Abboudi does not hesitate in answering the question on the first of his posters: “Bullitt, Steve McQueen, 1968.”

About 7,000 black and white images, together with film magazines on screenings in Lebanon, Iraq, Egypt, more than 800 political posters – Lebanese, Palestinian and Syrian – and another 200 on the topic of travel, fill the dense corners of his hidden labyrinth that we barely notice the sun setting down, the mueddhin calling to prayer, and the families of Hamra about to start their dinner: and we no longer know if we are in Beirut, or in Cairo, Rome, Paris, in Mumbai or in Damascus before the war.

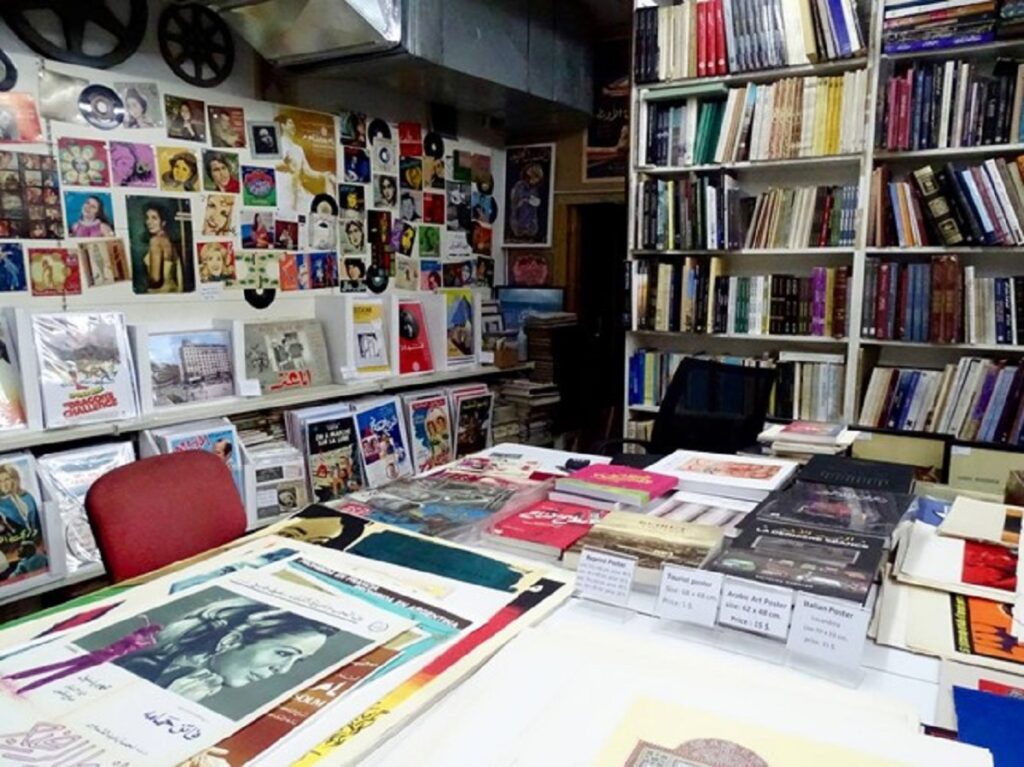

Part of Abboudi’s collection in his shop in Hamra. Photo credit: Valeria Rando

It is the magic power of archives, the infinite combinatorial potential of each of its pieces: collections that are not extinct, but which continue to grow, despite the fact that the culture they bear witness to is dying out – first with television, then with the internet, the tyranny of digital, of big shopping malls, and the whirlwind crisis which, if there is a lack of food and electricity, reasonably ends up cutting on culture. But it is also the power of individual memory that emerges as each poster, each title, the memory of each theatre unfolds.

Originally from the Armenian neighborhood of Bourj Hammoud, at the age of fourteen Abboudi used to go to the cinema four times a weekend, between Saturday and Sunday. The Rivoli cinema, in Downtown, was his favorite. “Sixty plates for the afternoon show.” What he loved most was taking long walks, walking along the East-West axis of Beirut, from Bourj Hammoud to Hamra, once the nerve center of Lebanese intellectual life, where artists lingered in cafés, and then went together to the cinema. For four hours, starting at ten in the morning, he would make his journey along Mar Mikhael, Gemmayzeh, Downtown, skirting the now devastated port, encountering more than thirty cinema rooms along the way: and dozens of posters posted for each.

“What has always attracted me are the images, I can’t explain why. If you ask me the plot of the films I went to watch, I can’t remember: yet in my memory I have imprinted the geography of the posters, the colors, the fonts in which the titles were printed.” And for each of his 20,000 posters he holds a specific memory, no matter whether the style was in bad taste. As soon as he spotted a new one, he used to return to the spot for days, three or four times at least, to observe it, to desire it. Then, when screenings were renewed, and new titles were released, he went looking for the old ones in small theatres in the suburbs, where he could afford them.

He started with Clint Eastwood, Steve McQueen, Burt Lancaster, Fairuz, Mohammed Abdel Wahab, Umm Khultum, spaghetti Westerns, the Hercules series, Maciste, spy films, James Bond, French actresses and actors, or the beloved Italians, Sofia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni. And over time, as the collection grew – so much so that not even the civil war stopped it – the six kilometers that separated Hamra from Bourj Hammoud became hundreds and hundreds, connecting Egypt to Tunisia, Morocco to Iraq and Syria.

Of course he no longer moved on foot, like the time he took a flight to Tunis just to be able to buy a poster from the 1940s: but the desire to add a piece to the collection, imagining its graphics and shades; the indescribable joy he felt when he saw the workman carefully removing a poster – and the longing to get it; the fluid movement of rolling up and unrolling; the sound of waving shiny paper; and so the chain of details that make the waiting pleasant and painful, at the same time, must not have changed much since the days when, as a boy, he walked for hours from his parents’ house to the cinemas in Hamra, stopping thirty-five times, then turning back, and always recognizing himself, his city.

In his long career Abboudi has met other collectors and archivists, but none as stubborn as him. “Collecting this type of culture is not popular in the Arab world: I might have met two or three collectors like me in Egypt, one in Syria, another in Algeria,” he says. “Mostly, you might come across some fanatics of Fairuz or Umm Khultum.” But lovers of the poster as such, of the material dimension of waiting for the screening of a new film only to see the paper promotion, when for a few hours the display cases are empty, and the imagination paints new bright colors on that white, empty space; and scenes of war, action, love, eroticism – in other words, of those like Abboudi – there aren’t many.

Part of Abboudi’s collection in his shop in Hamra. Photo credit: Valeria Rando

Perhaps this is why he is so successful: his passion did not stop him even during the fifteen years of the civil war, between 1975 and 1991, when cinematographic life in Lebanon surprisingly continued, with two screenings a day and a six o’clock curfew in the afternoon, and the temporary periods of respite, such as that of 1977, which he took advantage of to move his entire collection to the West side, where we are meeting today, fifty years later, sipping coffee. So that, the memories of death and bombings, of disappearances and fear, are combined with those, timid and pleasant, of the films he went to watch, even though incredulous that normal life, life as before, could continue in the beam of light of a projector in the half-empty dark velvet rooms.

Those who have lived through that life, now, coming across Abboudi’s world, are enthusiastic about it. They love the nostalgia of what they enjoyed spontaneously, the longing for a youth that time would have consumed anyway. They ask him: do-you-really-have-this-and-that?, and enchanted by such vastness, they bring up stories of family, grandparents, neighborhoods, and first loves. Some take photographs to send them to distant friends, so that the two realities – the surviving Beirut of today, and the boundless one of the Lebanese diaspora – meet in the half-buried archive of a basement, which to reach it, on foot, walking for kilometers from the other end of the city, these customers passionate about past lives, vestiges and nostalgia, who knows what they are thinking of.