The future of the electricity sector appears grim given Lebanon’s ongoing political paralysis and the Ministry of Energy and Water’s reliance on unsustainable solutions that are barely enough to keep Electricity du Liban ( EDL ) afloat.

Many agreements to save the production and distribution of electricity is hampered by a political cartel which has been ruling the sector.

An oil cartel ruling the sector

The ruling cartel was joined by the traditional political families under the cover of Lebanon’s leading political parties: the Future Movement (the Hariri family), the Free Patriotic Movement, the Lebanese Forces, the Progressive Socialist party (Walid Joumblatt) and the Marada Movement (Suleiman Franjieh). These parties had agents or ‘businessmen’ who managed the oil market and accumulated spoils and profits, which were then distributed to their corresponding political bosses, who remained in the shadows.

Over the previous three decades, Lebanon’s post-war reconstruction had been centered around oil dependence. Successive governments prioritized projects that maintained high fuel consumption levels – such as heavy investment in road infrastructure – and failed to support more efficient, alternative forms of shared transport and energy production. At the same time, Lebanese businesses and individuals received generous state subsidies on fuel, which blinded them to the true cost of imported oil.

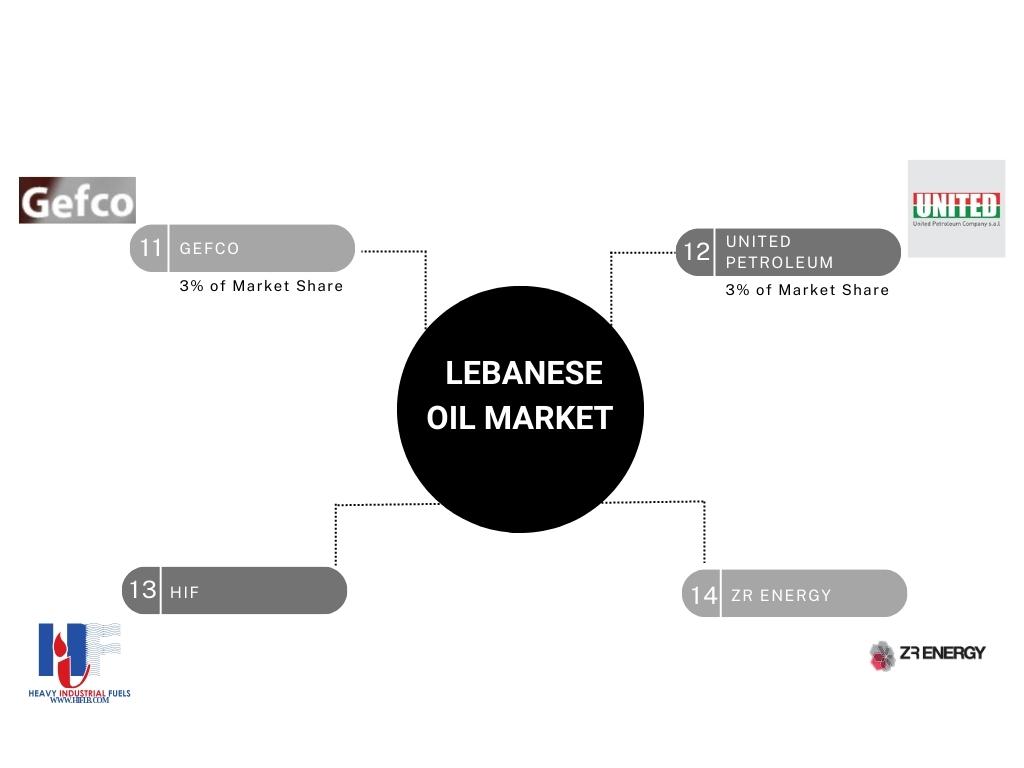

At present, an oligopoly of 14 importing companies dominates the sector – several of whom have blatant, demonstrable links to politicians or sectarian leaders. Commercial Registry records reveal that politically exposed people (PEPs) are current directors and / or shareholders in Cogico, Gefco, and Hypco.

Consequently, when there is risk of losing profits gained over the decades of this corrupt system, they withhold supplies of oil derivatives from the Lebanese market, causing the crippling shortages witnessed on a regular basis in Lebanon.

Some of these companies are also directly owned by Saudi citizens and Kuwaiti businesses. Today, 14 companies in Lebanon control both the import of oil derivatives and the distribution market. They also own half of the 3,100 gas stations in Lebanon and control the daily price of fuel. These companies control 70 percent of local market production, while just two Lebanese state facilities take the remaining 30 percent.

Sources revealed the names of oil companies that control the Lebanese market and the owners of some of these firms:

- Uniterminals, established in 1992, is owned by Kuwaiti and Lebanese investors, and holds 15 percent of the market.

- Coral Oil, founded in 1926, is owned by the Yameen family that supports the Free Patriotic Movement. Coral Oil holds 14 percent of the total market share.

- MEDCO, founded in 1910, is owned by brothers Maroun and Raymond Al-Shammas, and holds 11 percent of the Lebanese market share.

- Cogico, founded in 1986, is owned by Walid Jumblatt and the Basatna Company, is headed by Saudi citizen Mustafa Baltan, and holds 10 percent of the market share.

- Total, founded in 1951, is owned by the French company of the same name and holds 12 percent of the market share.

- Wardieh Holding, established in 1922, is owned by Saudi citizen Samuel Bakhsh and Lebanese shareholders. It holds 9 percent of the market share.

- Liquigas, founded in 1965, is also owned by the Yameen family and holds 7 percent of the market share.

- IPT Group, established in 1987, is owned by Michel and Toni Issa, who are close to former Lebanese President Michel Suleiman and holds 6 percent of the market share.

- Apec, founded in 1985, is owned by Abdul Razzaq Al-Hajjah, who is affiliated with the Future Movement. It holds 5 percent of the market share.

- Hypco, founded in 1965, is owned by the Al-Basatneh family in partnership with the (same) Saudi citizen Mustafa Baltan and holds 4 percent of the market share.

- Gefco, founded in 1982, is owned by Qabalan Yammeen and holds 3 percent of the market share.

- United Petroleum, founded in 1983, is owned by Joseph Taya, who is affiliated with the Lebanese Forces, and holds 3 percent of the market share.

- HIF, founded in 2008, is owned by Ali Zughaib and Pierre Obeid.

- ZR Energy, established in 2013, is owned by Teddy and Raymond Rahma, who are affiliated with Suleiman Franjieh’s Marada Movement. It is a new entrant to the original cartel stakeholders.

The Iraq deal

In 2022, Lebanon, Syria and Egypt signed a gas import agreement to import Egyptian gas through Syria in a bid to add four extra hours of power per day to the grid. The project remains mired in geopolitical challenges, with the emergency plan revealing that Egyptian natural gas is not expected to come online until at least 2028.

Another deal initiated with Iraq would have seen the supply of much needed fuel oil supplies. Desperate to secure a new supplier willing to engage with its cash-strapped economy, Lebanon signed the Iraqi deal in July 2021 for one million tons of fuel oil, or about seven million barrels. The agreement was extended in 2023 for an additional year, this time for two million tons, including a small volume of crude to be swapped alongside the heavy fuel oil. According to official documents from the Ministry of Energy and Water, Lebanon receives around half of the original fuel oil exported by Iraq.

But the exchange rates at which Iraq will access the funds as well as the exact nature of services are unclear. Lebanon’s energy ministry said it had picked Dubai’s ENOC in a tender to swap 84,000 tons of Iraqi high Sulphur fuel oil with 30,000 tons of Grade B fuel oil and 33,000 tons of gasoil. ENOC won the tender, part of a deal between the two countries that allows the cash-strapped Lebanese government to pay for 1 million tons of Iraqi heavy fuel oil a year in goods and services, reported Reuters.

As a result, Iraq has yet to access the $550 million worth of goods or services, the value of the first year’s imports, deposited in Lebanon’s central bank. The deal also leaves Lebanon reliant on fossil fuels as it swaps the Iraqi heavy oil for gas oil and low-Sulphur fuel oil, rather than cheaper alternatives such as natural gas, or cleaner renewables. Lebanon already owes Iraq about $1.59 billion for millions of tons of fuel already imported since 2021, according to figures from the Ministry of Energy and Water. The bank account assigned to the Iraqis at the BDL contains $550 million, the value of the first year’s imports. The Iraqi government has not yet accessed the funds, which are denominated in dollars but supposed to be withdrawn in Lebanese pounds.

Despite these issues, new documents suggest that Lebanon plans to rely on the Iraqi fuel deal being renewed for its energy supply until at least 2028.

Because the heavy fuel supplied by Iraq does not meet Lebanon’s fuel specifications, the deal allows Beirut to swap it on the international market for other types of oil suitable for its power plants, through traders who make a profit. But three years after the deal was signed, Lebanon has yet to pay Iraq for the oil received. This is partly due to the unclear terms of the agreement.

The contract, states that Lebanon will deposit funds in a dollar account that Iraq can withdraw in Lebanese pounds to spend on “goods and services” for its ministries, such as medical services.

The Beirut-Baghdad deal signed in 2021 was initially portrayed by Lebanese authorities as a gift from Iraq—a gesture of solidarity towards a fellow Arab nation grappling with an unprecedented economic crisis.

At the end of 2020, a fuel import scandal rocked the country. What Lebanese authorities had presented as a straightforward state-to-state fuel import agreement with Algeria was revealed to involve secretive offshore companies charging exorbitant prices for substandard fuel.

These revelations exposed a web of corruption involving contaminated fuel shipments, falsified laboratory tests, and widespread bribery of state officials. As a result, the fuel supply contract with Algeria was not renewed, leaving Lebanon without a fuel supply contract for the first time since 2005.

An alternative plan

Lebanon could become reliant on a complex arrangement to import Iraqi fuel for its electricity needs, despite the lack of an agreed repayment plan. The scheme, which experts say is fraught with problems, could lock the country into an unstable arrangement while delaying its transition to renewable or affordable energy sources, new documents and interviews reveal.

It all started many years ago, when well-intentioned (or so they claimed) politicians and technocrats embarked on a mission to illuminate the country. They promised the sun, the moon, and the stars, quite literally. Power plants were to be built, grids were to be modernized, and darkness was to be banished forever. But as the years rolled on, the dreams of an electrified Lebanon flickered like a candle in the wind.

EDL said that the dramatic tariff increases initiated in 2022 would enable it to cover the cost of Iraqi fuel. A reformulation of EDL tariffs to full dollarized scheme in 20223 has not yet resulted in revamping the future of the government power generation.

Experts questioned the rationale behind the emergency plan envisages renewable energy accounting for only 12 per cent of total production by 2028 in its best-case scenario, appearing to revise downwards the Ministry of Energy and Water’s earlier goal of 30 per cent by 2030.

Given current fuel costs, electricity must be produced at $0.20-0.25 per kilowatt hour.

EDL’s chronic losses, averaging $1.5 billion per year, have historically been the result of its expensive fuel supply. A recent study by the World Bank, the Lebanon Country Climate and Development Report, estimated that replacing fuel with natural gas and large solar installations could reduce the cost of electricity by 66 per cent in Lebanon.

Fast forward to the present day, and the situation is more farcical than ever. The lost money that was supposed to light up every home from Tripoli to Tyre has instead illuminated the depths of incompetence and corruption. Power plants stand like modern ruins—monuments to misplaced priorities and mismanagement. The lights go out with clockwork regularity, plunging the nation into darkness and despair.

The EDL’s electricity currently covers three to six hours on average depending on the area. There are very few areas that exceptionally have a high number of hours of electricity coverage such as Jezzine district, which is at an average of 14 to 20 hours. In a March 2023 study conducted by Human Rights Watch and Consultation and Research Institute (CRI) which covered 1,200 households, it was found that the cost of electricity has affected nine out of ten households’ ability to pay for other essential services. Low-income households were mostly affected by the rising costs as they had to sacrifice other essentials that they were barely even able to access. Furthermore, the study showed that amongst the poorest 20 percent of households, one in five cannot afford access to a generator which is the sole available source of a more stable electricity supply.

Stalled reforms

The core issue of EDL negative performance is that Lebanon has never developed a comprehensive energy strategy. The discussion has predominantly focused on electricity: its source and the state’s role in procuring it. Recently, the focus has shifted to oil and gas as the primary sources of electricity, capturing both political and public attention. Renewable energies like solar and wind have received considerably less attention and enthusiasm, despite initiatives for both fossil fuels and clean energy being introduced simultaneously in 2013. Bureaucratic hurdles and political disputes have led to a severe power shortage, with neither gas nor renewables filling the gap. The severe economic downturn that began in late 2019 only intensified the crisis, plunging some areas of Lebanon into complete darkness. Lebanon’s National Emergency Plan for the Electricity Sector, written by the Ministry of Energy and Lebanon’s state electricity company, Electricite du Liban. It was put together as an alternative to the country’s 2022 energy plan, which has not yet been implemented amid delays in the wider package of reforms to Lebanon’s governance and economy demanded by international lenders in return for vital funding.

The plan reveals that EDL intends to increase the volumes involved in the deal with Iraq to $772 million per year. This is part of its plan to boost capacity production from four hours to eight hours per day by 2028.

According to calculations, this will increase the total bill owed to Iraq to $5.45 billion by 2028, and leave Lebanon mainly reliant on fossil fuels, without guaranteeing 24-hour electricity for residents.

For decades, Lebanon had poured an astronomical sum—USD 40 billion—into its electricity sector. This vast fortune, which could have funded countless moon missions or built entire new cities, was funneled into the bottomless pit of the Lebanese power grid. Yet, despite this colossal expenditure, electricity remained as elusive as a unicorn in the Bekaa Valley.

Generators and cancer

In the absence of reliable electricity from the state, a new power emerged—literally and figuratively. Enter the neighborhood power generators, the true lords of Lebanon’s electrical domain. These diesel-fueled behemoths, belching black smoke and noise, have become the lifeline of the Lebanese people. Owned and operated by an unofficial yet omnipresent entity—the generator mafia—they have carved out fiefdoms in every corner of the country.

Lebanon, where the power grid is as reliable as a politician’s promise, the rise of lung cancer has become an unexpected side effect of the nation’s dependence on power generators. As these diesel-chugging behemoths puff out clouds of carcinogenic joy, residents are treated to a free, albeit deadly, respiratory workout. It’s almost as if the air itself is conspiring to remind everyone of the Usd40 billion spent on a non-existent electricity system. With each breath of generator-scented air, the Lebanese people can take comfort in knowing their lungs are as battle-hardened as their spirits.

These generator owners are no ordinary businesspeople. They are the new-age mafiosi, wielding power (pun intended) that rivals that of the government. They set the rules, dictate the prices, and control the supply with an iron fist. Need an extra hour of electricity? That’ll cost you. Want to run your air conditioner in the sweltering summer heat? Get ready to pay a small fortune. In a land where the official currency is the Lebanese pound, the generator mafiosi deal exclusively in US dollars, cashing in on the despair of the populace.

And so, the tale of Lebanon’s electricity saga marches on, a never-ending story of grand ambitions and dismal failures. The generator mafia thrives, the power plants rust, and the politicians continue to spin their webs of promises. The people of Lebanon, ever resilient, adapt and endure, their spirit undimmed by the darkness that surrounds them.

Lebanon’s dysfunctional electricity sector has always relied on private generators, which are technically illegal but tolerated as the only alternative to make up the shortfall from EDL’s supply. According to an AUB research, the density of generators in Beirut remained stable over the years – averaging one for every two buildings, or around 9,300 generators.

But after the 2019 economic crisis, as the state’s power supply shrank from 21 hours in Beirut to just a few hours a day, generators became the primary electricity provider.

As a result, the risk of developing cancer over a lifetime has risen by 50 cents since before the crisis, the study found.

AUB study calculated cancer risk based on the chemicals emitted from generator exhaust, including some classified as category 1A carcinogens. According to WHO figures from 2020, lung cancer is the third most prevalent cancer in Lebanon, after bladder cancer and breast cancer.

Cancer patients have been significantly affected by the economic crisis, facing medication shortages and soaring prices for treatments, when they are available on the black market, as public healthcare services crumbled.

There is a high demand of a monthly 1,500 to 2,000 people requesting services unable to afford their medication.

Where do we go from here

The Lebanese electricity saga is not just a tale of financial mismanagement; it’s a story of resilience and adaptation. The people of Lebanon, faced with relentless blackouts, have developed a unique set of survival skills. They juggle between the state electricity supply (when it sporadically appears) and the generator power, mastering the art of electrical alchemy. They have learned to prioritize their energy consumption, deciding which appliances are worthy of precious watts and which must remain dormant in the darkness.

In the villages and towns, the sight of children doing homework by candlelight has become a poignant symbol of the nation’s plight. Businesses, large and small, factor in generator costs as a line item in their budgets. Entrepreneurs have sprung up, specializing in solar panels and alternative energy solutions, hoping to offer a glimmer of hope in an otherwise bleak landscape.

Yet, despite the ingenuity of its people, Lebanon remains shackled by its electricity woes. Auditors and investigators occasionally peek into the abyss, only to find a labyrinth of paperwork, ghost projects, and vanished funds. The mystery deepens, and the truth remains obscured by a fog of bureaucracy and deceit. And this can go on for years…

In this land of contradictions, where luxury cars navigate pothole-ridden roads and gourmet restaurants operate next to dilapidated buildings, the electricity saga stands as the ultimate paradox. A country with a history stretching back thousands of years, boasting achievements in art, science, and culture, remains unable to solve a problem as fundamental as keeping the lights on.

In the end, the Lebanese electricity saga is more than just a story of financial waste and corruption. It is a reflection of the nation’s struggle, resilience, and hope. A satirical mirror that shows us the absurdity of a situation where billions are spent, yet nothing is gained. A reminder that in the land of the cedars, even in the darkest of times, the light of the human spirit shines brightest.

Maan Barazy is an economist and founder and president of the National Council of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. He tweets @maanbarazy.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW.