“I knew him.”

“She was my neighbor.”

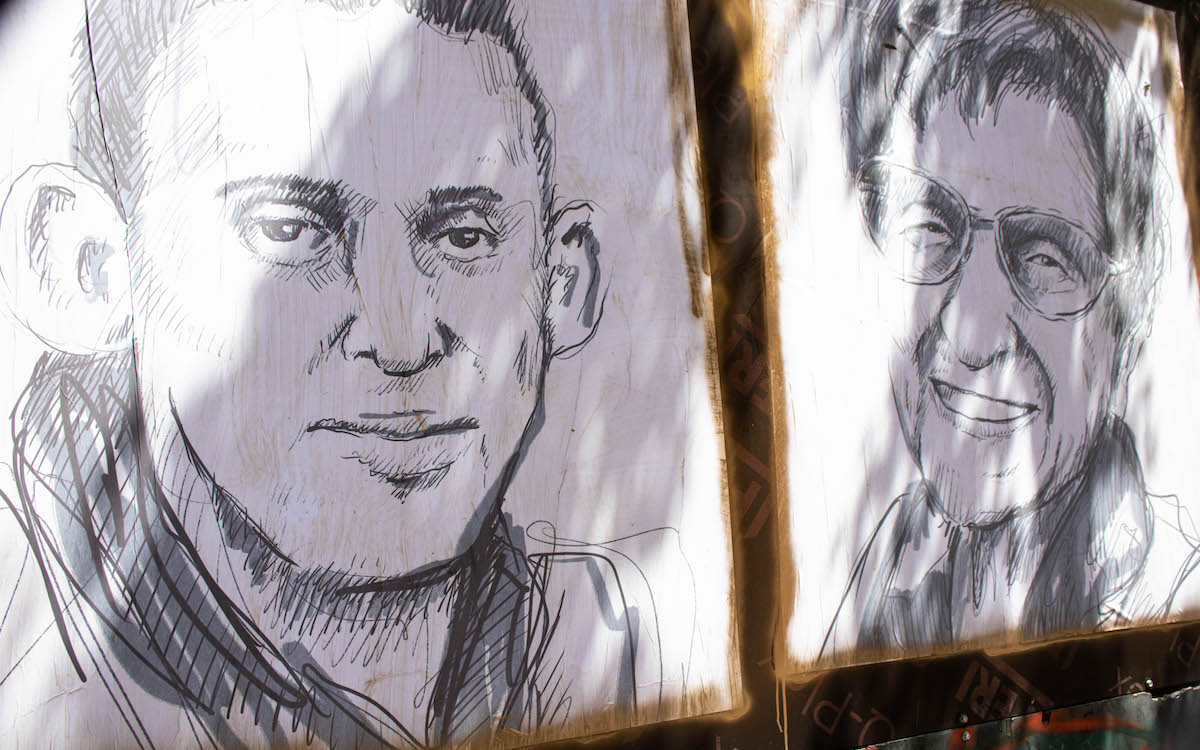

The man pointed to several portraits of people that he once knew as he walked with American artist Brady Black along the plywood walls next to Martyrs’ Square, Central Beirut, to find the most important picture to him. His father’s.

Over the last three months, the 43-year-old artist has been drawing portraits of the over 200 victims who died in the August 4 Beirut Port explosion. On the nine-month anniversary of the explosion, May 4, he finally put the portraits up near Martyrs’ Square.

Black had not been expecting one of the victims’ family members to show up. But he was more than happy to show him where the image of his father, Varoujan Tosunian, hung on the beaten-up walls.

“It feels just as bad as the day of the explosion,” Varoujan’s son told Black. “Four men had to carry him. There were no ambulances coming. Glass was stuck in his head. There was blood everywhere.”

Black, despite the fears of the coronavirus, hugged the grieving man on instinct as he recounted his final moments with his father.

“I was really worried how their [the victims’] families would react,” he said.

From Texas to Beirut

Black was born and raised in Texas and did not anticipate becoming an artist, much less one doing street art in the Middle East.

He only really started drawing as a coping mechanism when he was already in his thirties after his mother became ill and he was taking care of her full-time for nearly a year and a half. Upon finding a book on graffiti at a bookstore, he says he decided to try his hand at illustrations despite having had no idea what they were.

“I was really just struggling with that. Like it was kind of making me crazy,” he told NOW. “So I started trying to draw and I was suddenly drawing a lot. It was helping me cope with the difficulties of [my mother’s illness].”

A few years later in 2014, after his mother had recovered, Black got a job teaching English at Sultan Qaboos University in Muscat.

Despite having a job while he and his wife, Amber, were living in the Gulf, his passion for art was still able to flourish thanks to the help of Amber.

After about a year in Oman, the couple moved to Beirut to open a school for abused and abandoned children.

In 2016, Black discovered a new form of art after he heard about Lebanon’s urban sketchers, people who draw images while they are at the scene, while at an art salon. He then joined their WhatsApp group and showed up during one of their outings in Sodeco.

While the urban sketching scene in Lebanon is not huge, with some of them being full-time artists and others just doing it for fun, the group’s passion for what they were doing rubbed off on him.

“I just really fell in love with that because I used to be really interested in photojournalism and taking pictures and a lot of street photography was really my scene,” he explained.

“I really kind of found a niche where my street photography and urban sketching really melded well together because I’m too scared to stick a camera in someone’s face. But I can draw so I ended up just being able to draw the pictures that I couldn’t take.”

However, Black had to set down his pen and paper in October 2019 to help Amber with the school and the children that they worked with.

He did not have to wait long, though, before he could break out his sketch pad again.

“When the revolution started, I didn’t know what was going on,” Black recalled with a chuckle. “Then one of my neighbors was like ‘You need to come with us.'”

Drawing the Lebanese protests

For the first 100 days of the uprising, the artist spent his time in the Beirut streets just drawing what he saw. He then posted his drawings on his social media accounts, allowing anyone to use them copyright-free.

“The first day I went down and I drew a bunch [of] live [sketches] and then I started putting them online and people began to respond positively,” he said. “So I was like ‘These are for you [the Lebanese people]. You use them for whatever purposes you want.'”

It was not always just drawing crowds of people chanting and waving flags.

In December, when the protests started taking a more violent turn, Black stayed in the streets, sketching the clashes between protesters and security forces while tear gas, rocks and fireworks fell around him.

When he saw people being beaten by security forces and old men covered in blood being carried away, Black felt a responsibility to continue to document what occurred even though he himself was sometimes targeted by the security forces.

“I had cops in my face, with sticks in my face. They would knock my pad out [of my hands] and step on it,” he recalled. “Then suddenly the rocks were coming from the direction of the army. I was like ‘Woah. Shit. That’s the wrong direction for that rock to be thrown.’’

For Black, seeing the security forces throwing stones at the anti-government protesters and not vice-versa, something that he called “injustice,” changed his feeling of how he was connected to the protests. Rather than feeling like a “third-party person documenting people doing yoga in the Ring,” he began to feel a deeper connection to the Lebanese people who he drew daily as he was witnessing their uprising.

However, as more and more people started getting detained by security forces, Black had to make the challenging decision of not going out as much.

Soon after, the Covid-19 pandemic reached Lebanon and everyone was stuck indoors to prevent the spread of the virus.

But it was in October 2020 when Black developed a new passion: creating public art.

Giving a voice to the voiceless

After meeting members of Art of Change, a collective of artists specializing in urban art during the uprising, Black started getting involved in what he likes to call “mischief,” often posting on his social media accounts whenever he planned to put up a new art piece on the streets of Beirut, usually under the cover of night.

In October 2020, he completed an art residency at Art of Change where his sketches of the uprising were exhibited, but he also decided that he wanted to challenge himself.

Every day for 31 days, he would create a new piece of art that he would then paste on a wall on the streets of Hamra for anyone passing by to see. Often, these pieces would be of the homeless children that roam the streets of Hamra every day, in the hopes of honoring the presence of those who are often ignored.

“I just started seeing what that did for people, this idea of ‘man, you’re seen,'” he stated. “Who paints portraits nowadays? Who has a portrait painted of them? Rich people and important people, presidents and governments and stuff. It was like ‘Here I am. A shoe shiner and I have a big ass life-sized portrait painted of me.'”

It was after doing this that he “fell in love with the idea of public art and the role that it can play in society.”

Black compared public art to advertisements on billboards: advertisements did not “ask for permission” to be in people’s faces, so he was not going to ask for permission to put up his art pieces for everyone to see.

Public art is not simply activism according to Black, nor is it just giving people a voice.

“I think it’s a mixture of both,” he explained. “Depending on the subject matter, maybe I’m an activist because I want to challenge you on these things and, then, I also want to give the voice to the people.”

He gave the example of his “Beirut is Screaming” series where he made portraits of Lebanese people screaming. Black said that this was not him trying to be an activist, but his attempt at expressing how the Lebanese people were feeling amid the various crises that plague the Mediterranean country.

View this post on Instagram

With his portraits of the victims of the Beirut Blast, he says he wanted to give people a physical place to mourn their lost loved ones and, sending a message criticizing the Lebanese government’s lack of action and the lack of results from the investigation into the devastating explosion.

But for Black, drawing the streets of Beirut is ultimately about giving people back their names so that they’re remembered by the passer-by.

“I’m not asking you to fix anything,” he explained.

“I’m just asking you to know their names. When you know their name, then it’s totally different. That’s Rahaf running down the street. And she comes up to you and asks ‘How are you? How’s your mom?’ And now she’s your neighbor. She’s not [just] some pest on the street.”

Nicholas Frakes is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. He tweets @nicfrakesjourno.