IMF closer to a Zero interest coupons proposal

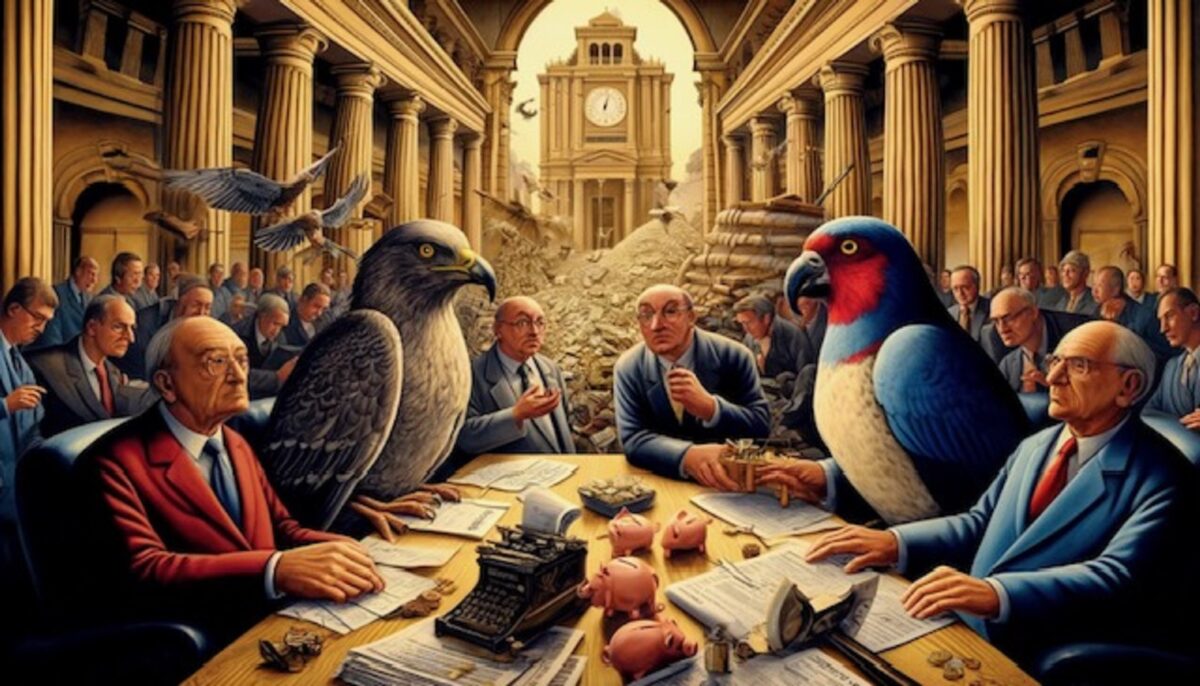

In a grand display of financial theater, the Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL) recently unveiled their latest proposal for returning deposits. The doves, on the other hand, cooed softly about the impracticality of the plan. “Think of the logistics,” one dove implored, “How many circulars does it take to buy a loaf of bread? And where do we even find them?” The hawks countered that any solution could stimulate the economy, and allow them to engage in a lender of last resort situation once more.

Hawks and doves

In Lebanon’s grand banking halls, hawks and doves converge, to debate the IMF’s counsel, a spectacle to observe. Hawks clutch their ledgers, feathers bristling with disdain, “Debt forgiveness? A flight of fancy, an economic stain!” In short, the Hawks don’t want to allow for a measure that will return deposits of more than Usd100,000 and are in favor of a 10 years plan to install those.

One of the most prominent symbols of this camp is Bank Audi, which organized the last luncheon with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Looking back at the history of this bank, we are reminded of its significant issues with solvency and liquidity that arose in the years leading up to the collapse, due to the losses incurred by its branch in Turkey. At that time, the bank had to rely on financial engineering operations from the Central Bank of Lebanon to compensate for its losses, before these operations were generalized to all Lebanese banks. After the collapse, and three years ago, the bank completed a deal to sell its branches and assets in Egypt to the First Abu Dhabi Bank. At that stage, the deal injected more than Usd660 million into Bank Audi’s accounts, according to some circulated information, which allowed the bank to comply with the fresh dollar liquidity level required by the Central Bank of Lebanon. Then, in the same year, the bank liquidated its branches in Jordan and Iraq, selling them to Capital Bank. In summary, the acceptable liquidity levels currently enjoyed by Bank Audi, compared to other Lebanese banks, were primarily driven by its ability to liquidate a bulk of its foreign assets. This does not place the bank in a “sound” position in terms of solvency, but it remains more capable of securing the minimum funds required to guarantee small deposits, according to the recovery plan.

Blom Bank – the second largest Lebanese bank – stands out among the realistic banks that accept the conditions of the restructuring path. Like Bank Audi, Blom Bank benefited from the sale of its branch in Egypt to the Arab Banking Corporation in Bahrain after the collapse. Overall, the general manager of the bank, Saad Azhari, appeared more rational in addressing the restructuring issue in all media interviews, compared to the tense rhetoric of other banking leaders. Just like Bank Audi, the Azhari family still holds a significant series of foreign assets in the form of sister banks, investments, and foreign branches, which serve as a fallback option when needed to recapitalize the parent bank in Lebanon.

In the dovish camp, we also find the names of three other major banks: Bank Med, Banque Libano Francais BLF, and Byblos Bank. The common factor among all these five banks is either the solvency of shareholders interested in maintaining their entities in Lebanon or the availability of an acceptable level of liquidity compared to other banks.

Notably, the three largest Lebanese banks in terms of assets – Audi, Blom, and Byblos – together held more than 42% of total banking assets and a similar percentage of deposits before the collapse. Nevertheless, these banks have limited influence on the decision of the Association of Banks, where voting adheres to the principle of one vote per bank, regardless of its size. This gives smaller banks the power to decide within the association.

Meanwhile, blacksmiths across the country prepared for a sudden surge in demand, and bankers began brushing up on deposits whereabout. Amidst this chaos, the only clear winner was irony, which celebrated its own devaluation as the ABL’s proposal echoed through the annals of absurdity. Mind you the political junta has stakes in Lebanon banking system and any debate is politics not monetary.

IMF talks in Lebanon

Though Lebanon “did make progress” on economic reforms required by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in a staff-level agreement (SLA) two years ago, the country is still not close to meeting its end of the deal to unlock much needed funds to revive the ailing economy and restructure the banking sector.

In a display of bureaucratic ballet, Lebanon’s progress in satisfying the IMF’s demands has been more akin to a slow waltz than the expected sprint. It’s been two years since Lebanon struck a staff-level agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), promising access to a Usd3 billion lifeline over four years—conditional, of course, on a series of fiscal, financial, and monetary reforms that would make even the most seasoned politician’s head spin.

Recently, an IMF team led by the ever-diplomatic Mr. Ernesto Ramirez Rigo, graced Beirut with their presence from May 20 to 23 to take stock of the economic situation and reform progress. In their understated manner, the delegation noted that the “policy measures fall short of what is needed to enable a recovery from the crisis.” Translation: Lebanon is still miles away from meeting the IMF’s checklist. Bank deposits remain as frozen as a Middle Eastern winter wonderland, and the banking sector is about as creditworthy as a lottery ticket.

The IMF’s statement underscored that the Lebanese government and parliament seem to be playing a game of ‘hot potato’ with the banking crisis, unable to find a solution that addresses the banks’ losses while protecting depositors. Meanwhile, Lebanon’s cash and informal economy continue to blossom like wildflowers in a regulatory wasteland, raising alarms about supervision and control. In essence, without real progress, Lebanon’s economic future remains as uncertain as a politician’s promise.

Zero coupons deposits

A joint proposal by Government and the Monetary Authorities for a solution for USD deposits exceeding Usd100,000 that are currently stuck in the banking system is on the burner, NOWLEBANON has learned. The proposed architecture involves issuing depositors USD zero-coupon marketable bonds equivalent to their original deposit amounts, which would be redeemed after 40 years. Additionally, deposits of up to Usd100,000 would be returned to depositors in full, presumably over the same period.

This justifies the drive by some banks to engage in dialogue outside the umbrella of the Association of Banks. It appears that the IMF is becoming more open to this idea, under certain conditions, while some sources indicate that the Central Bank of Lebanon itself sees this concept as a way to address part of the accumulated loss gap in the sector. The circulation of such proposals, which are accepted by the less extreme banks, explains the enthusiasm of this segment of banks to discuss more rational “compromise solutions” compared to those officially adopted by the Association of Banks. This segment of bankers has come to understand that the association’s recklessness will drive the entire sector into the abyss if the status of “zombie banks” is normalized in the long term.

This situation only benefits bankers who are either unable or unwilling to recapitalize their banks and ensure the minimum for each deposit. These individuals currently dominate the Association of Banks due to their numerical majority, even though their smaller banks represent only a small fraction of the sector’s assets and fresh dollars.

Where does the solution come from ?

In 1992 investors were drawn to exciting advertising by Industrial Development Bank of India (IDBI), a Central Government Development Financial Institution, calling for subscription to its Flexi-Bonds. The terms were mouth-watering, offering bonds with a face value of Rs. 1 lakh for Rs. 2,700. The face value of Rs. 1 lakh on each bond would be paid to the investor in 25 years. No surprise that the bond issue received a tremendous response.

Hitherto only institutional investors had access to such products through “Treasury Bills” or T-Bills issued by the Reserve Bank of India. T-Bills are issued with a face value of Rs. 1,000 each, at a lower price. The holder earns that difference in price till redemption at Rs. 1,000. Treasury bills were first issued in India in 1917. A regular auction of T-Bills was started by the RBI in 1987. The issues are like Deep Discount Bonds (DDB).

IDBI exercised its call in 2002, 10 years after the issue, and paid the investor Rs. 12,000 as advertised. (The investor earned just a little more than double every 5 years – a return of over 14% compounded annually. For easy measurement tools check out the 11th article in this series, “A measurement of returns”. The Rules of 72, 69, or 144 provide tip-of-the-finger comfort in working out the rate of doubling money).

The ABL position

Last week the Association of banks reiterated its position underlining the State Council’s Decision No. 209 dated 2024/2/6 in its ruling paragraph, which states that “the decision to cancel a large part of the Central Bank of Lebanon’s foreign currency obligations towards banks, which represent deposits made by depositors in private banks, without these banks fulfilling their obligations to return deposits on demand according to Articles 690 and subsequent of the Code of Obligations and Contracts, constitutes an obstacle preventing this from happening without any delay”.

It also considered that this is a “breach of professional obligations imposed on banks regarding the protection of depositors’ rights and funds, and the necessity to return the deposit to its owners in a manner that ensures actual fulfillment without causing them any harm or depriving them of effectively accessing or using their funds productively”.

In light of the above and given the proven violation of the Cabinet’s decision, in its contested part, of constitutional principles, principles derived from international agreements, and national laws (the Code of Money and Credit, the Code of Obligations and Contracts), the mentioned decision is annulled, and any measures taken based on this decision are considered clearly contrary to constitutional provisions and applicable laws, it quoted.

Accordingly, the ABL considered that “any negotiations conducted by the association or opinions issued regarding any draft law related to the restructuring of banks ( … )must include a clear and unequivocal text stating that the current financial crisis in Lebanon is a “systemic crisis.”

The state must bear all its legal obligations, especially concerning covering the losses in the Central Bank’s balance sheet, thereby placing the responsibility on the state and its central bank to return all deposits from the Central Bank to the banks so that they can fully return them to the depositors, it concluded.

Deposits losses – looking for a scapegoat?

Is the Narrative that Loan Repayments with Bank Checks or in Lebanese Pounds Responsible for Deposit Losses an Absolute Truth? Banking experts say: The real loss from loan repayments after the crisis came from only two sources:

Repaying retail loans in Lebanese pounds instead of dollars (this was imposed on banks by the Central Bank of Lebanon). Another loss happened as banks accepting the repayment of loans in fresh dollars with a discount on the nominal value. (For example, a bank might accept Usd20,000 in cash from a depositor to settle a loan of Usd35,000). These losses were accepted by the banks knowingly and deliberately, on the basis that they would later be assessed on liquidity ratios, not on losses. This was before the Central Bank of Lebanon issued a circular preventing banks from continuing this practice.

In other words when repaying loans with bank checks, the deposits are reduced by an equivalent amount, particularly if the check is issued by the same bank. In this case, the bank’s liabilities and assets both decrease by the same amount, resulting in no loss for the bank. However, if the check is issued by a different bank, the second bank incurs the loss. Consequently, banks have refused to accept bank checks issued by other banks for loan repayments. It’s important to note that this process does not impact the banking sector as a whole, as it does not affect the consolidated balance sheet of the banks

A significant portion of these loans would not have been repaid at all and at least half would have turned into bad debts. This would have resulted in widespread chaos in the courts and legal system due to banks executing their collateral and foreclosing on defaulters, especially regarding real estate loans.

Jean Riachi Chairman of FFA private bank tweeted: “I remember a conversation in early 2020 with a very wealthy neighbor and friend, where I told him that large depositors would not escape the haircut due to the magnitude of losses in the financial system. His response surprised me: “Give me any title deed with the nominal value of my deposit, and I’ll be satisfied.”

As for Riachi this dialogue illustrates what depositors are asking for. They know their money no longer practically exists, but they want it to remain legally guaranteed in case of what is called a “return to better fortune”. In this regard, the deposit recovery fund is a better formula than zero coupon bonds. This fund, issuing ownership titles with a nominal value equivalent to the deposits and remaining valid until final repayment, allows for combining different sources of revenue, particularly – when accountability becomes possible – by making those who abused the system pay. Additionally, in the event of political recovery and economic resurgence (anything is possible), the fund’s replenishment will accelerate, especially through gas revenues and other surplus revenues allocated to the fund without impacting the state’s needs.

A Zero Coupon Bond makes no periodic interest payment, but instead it usually offers discounts on its face value. The earnings accumulate until maturity, when they are redeemed at face value on a specified maturity date.

The deposit recovery fund

A solution for Riachi is that banks should start by immediately distributing the liquid assets of the banking system, including a significant portion of the Central Bank’s gold, and quickly activating the liquidation of other assets, including real estate and holdings in Lebanon or abroad belonging to the financial system, as they are depositors’ rights. Besides being the depositors’ right, injecting this liquidity into the economy will have a very positive effect.

Zero coupon bonds also allow for giving a bond with a nominal value equivalent to the deposit. But this is not about a return to better fortune; it’s about compensating the depositor with their own money by investing the available liquidity on their behalf, then asking them to wait 30 years for the accumulation of interest to take effect. This solution is purely cosmetic, while the recovery fund, if designed intelligently, is not cosmetic, even if the promise of full repayment is very long-term.

The major difference is that if the deposit recovery fund solution is adopted, the available liquidity can be distributed to depositors instead of being frozen to fulfill the promise of nominal value repayment at maturity, as in the case of zero coupon bonds. Not to mention that the Lebanese economy benefits from distributing this liquidity to depositors instead of lending it to foreign parties for thirty years!

No doubt, the solution is novel, clever, and potentially sellable as it promises depositors their full amount in the long-run. For those with shorter and impatient time frame, they can trade their bonds in the market at a discount. Two hiccups remain: first, the discount would not be small; second, would the bonds assume all the eligible USD deposits or be part of a Deposit Recovery Fund?

Where do we go from here?

Ultimately, the most crucial milestone today is the upcoming elections of the Association of Banks, which will shape the future direction and role of the association. Suppose the elections result in the renewal of the current leadership, which is more resistant to any path leading to serious sector restructuring. In that case, the association is likely to face further division, fragmentation, and lack of purpose. Conversely, the emergence of new leadership with more realistic visions and a greater willingness to pursue restructuring is the only development that can restore the association’s role. This path should lay the foundation for revitalizing the banking sector and addressing its gaps by distinguishing between banks capable of continuing and returning the minimum deposits and those that reject such realistic solutions.

Maan Barazy is an economist and founder and president of the National Council of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. He tweets @maanbarazy.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW.