On a sunny Saturday, in the outdoor garden of Social House Beirut café, Lebanese author Joumana Haddad and Palestinian-Canadian writer Chaker Khazaal were talking about his work, in which he includes personal journeys of pain, suffering, and psychological conflict.

“It’s easy to delight in your natural ability to poke fun at yourself as you plot your escape to find your rightful place in the world,” Joumana told Chaker.

The English Book Club at the Joumana Haddad Freedom Center (JHFC) had convened for one of their bi-monthly meetings to examine Khazaal’s latest book, “Ouch,” in which he depicts his mission of escaping refugee camps and find his “rightful place in the world.”

Haddad, Lebanese author, and human rights activist, ran for parliamentary elections in 2018 on the list of Kuluna Watani secular coalition and she lost. Only one candidate on the secular list, Paula Yacoubian, actually made it to the Lebanese Parliament after an electoral campaign that saw the women candidates harassed and threatened. Kullouna Watani’s delegates were kicked out of 15 percent of the voting centers in the Beirut district where Haddad ran. Another female candidate, Rima Hmayyed, was assaulted outside a polling station in southern Lebanon by supporters of Hezbollah and Amal, who control the constituency.

For Haddad, it was clear that the glass ceiling was far too high. To break it she needed to work more at the grassroots level and empower a new generation through reading, thinking, and discussing what society at large still sees as taboos. The answer, she says, is not only to empower women but also to tackle the social structures that allow violence and marginalization of women in Lebanon.

She started the book club in 2020 to encourage young Lebanese to think critically. That is where the change needs to begin in order to get progressive-minded readers, she told NOW.

“The feminist movement was always elitist and rather alienated from broad-based social matters in Lebanon,” Haddad said.

“We have been claiming to empower women for far too long now. The time has come to empower, educate, and tackle the roots of where all these violations occur. I see the opportunity with the book-club structure to create a powerful tool to showcase our ideas.”

The fight for one seat

Looking back at the months leading up to the elections, Haddad said that the reason for what had gone wrong was not the lack of proper education or the women candidates’ credentials, but, for the most part, the prevalence of fear-mongering as a tool used by the ruling political parties to scare the public away from inviting women into political and public office.

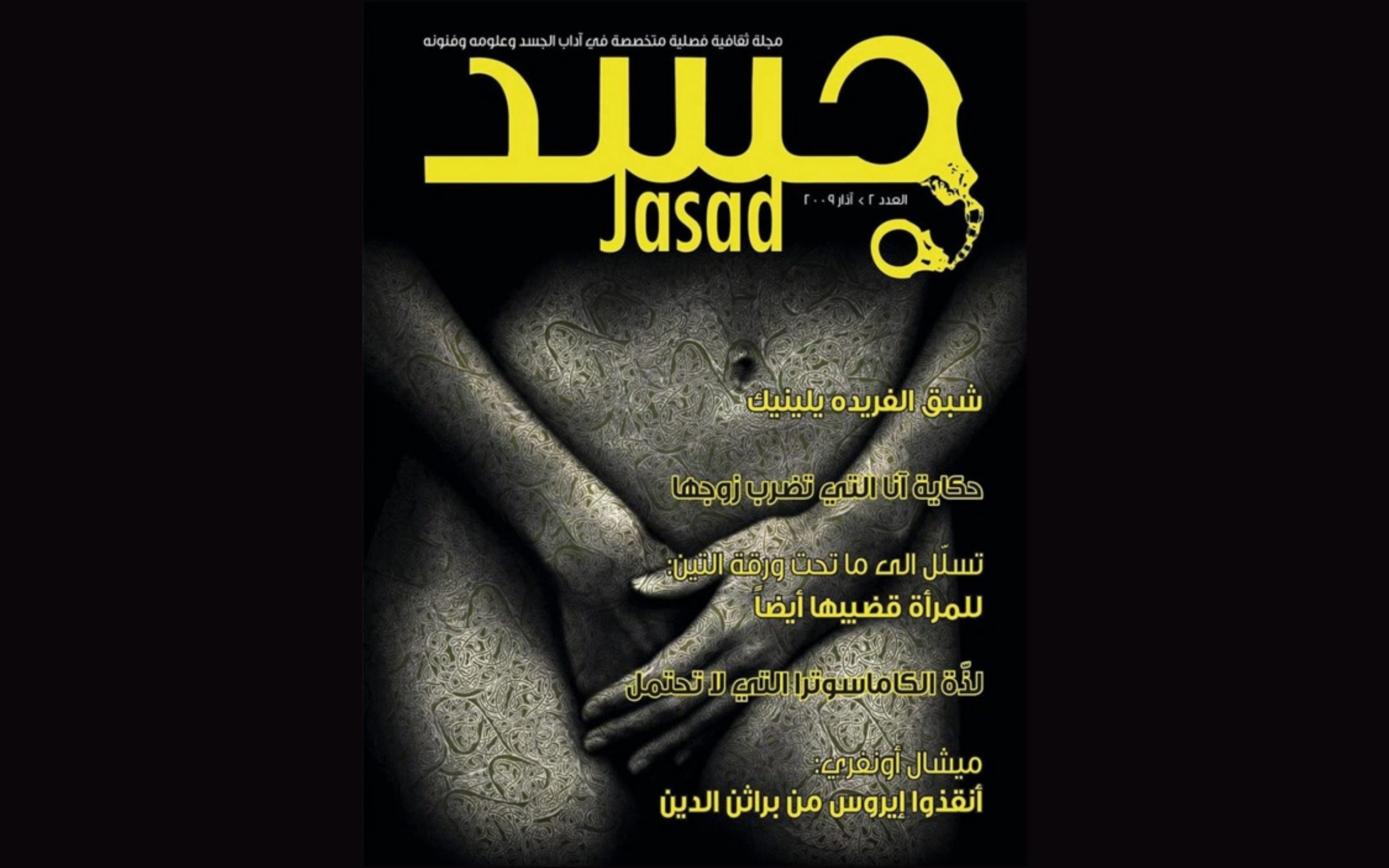

Haddad herself did not lack competency. Originally a journalist writing for one of Lebanon’s leading newspapers An Nahar, she founded in 2007 Jasad magazine “to shine a spotlight on Arab cultural taboos”.

“The magazine has found an audience, a sign of the hidden hunger here for candid discussions of normally off-limits topics,” Haddad said NOW, highlighting that most subscribers were Lebanese. Still, many were from other countries in the region, especially Saudi Arabia.

The magazine has drawn the wrath of religious authorities and women’s organizations in Lebanon, who called for its closure, claiming the publication amounted to pornography. Haddad received threats in 2009 and was afraid to leave her home for weeks for fear that her critics’ threats to throw acid at her would realise.

She made it to the top 100 most powerful Arab women in March 2014 in CEO magazine the Middle East for her cultural and social activism. She has several poetry collections that have been published in a variety of languages and her most well-known book “I Killed Scheherazade: Confessions of an Angry Arab Woman” has motivated women across the region.

She has received several awards over the years, including the Arab Press Prize in 2006 and the International Prize North-South for Poetry in November 2009. In February 2010, she was awarded the Blue Metropolis Al Majidi Ibn Dhaher Arab Literacy Prize. She won the Rodolfo Gentili Prize in Porto Recanati, Italy, in August of the same year.

Although a victory for Haddad had initially seemed likely, with supporters wildly celebrating early exit polls the night before the official turnout of the results, she lost. Her supporters gathered outside Beirut’s Interior Ministry to protest when results showed she had lost. The elections were rigged, they said, pointing out the many apparent violations during the poll.

A day after the parliamentary elections, at around 5 am, every political party had run the numbers and triple-checked the exit polls. Kullouna Watani members were certain that Yacoubian and Haddad had secured two seats in the Beirut 1 District. Yet, at around 6 am, all candidates and their representatives were kicked out of the vote-counting center in the Forum de Beirut area after several envelopes without the red wax seal had gotten in under the excuse that “the room doesn’t fit” and “IT problems”, Haddad remembers.

It wasn’t till after 7 am that candidates were let in after threats to go public about violations of the electoral law.

“Before we were kicked out, Kolluna Watani, our party, had a little over 1.6 “7asel” (threshold), which translates to two seats: Paula Yacoubian and I. After the party’s team was let back in, the number magically dropped from 1.6 to 1.2. This was exactly what was done to Beirut Madinati [in the 2016 Municipal elections]. Phantom boxes, kicking out reps and candidates and a sudden change in the result,” she said.

Protesters demanded the resignation of Nouhad El Machnouk, who was the Minister of Interior and Municipalities at the time; they threatened to hold their ground until Haddad’s seat was reinstated. According to Haddad, exploring the potential of a collective “No” that builds strategic refusal to engage with an unjust system is worth exploring.

“But when the local authorities, especially ones involved in the ministry of interior, at the time, gave the order to vacate the street with a pledge to refer the case to the proper legal channels, the protesters had no choice but to disperse,” she said.

Gender discrimination in politics

Women have had little room in Lebanon’s political establishment over the decades, despite attempts to set quotas for political parties to promote more women candidates. This type of marginalization has pushed women towards civil society activism, resulting in women spearheading social movements demanding structural change in Lebanon.

“The women’s movement is the driver for change and hope in Lebanon,” Carmen Geha, Associate Professor of Public Administration, Leadership, and Organizational Development at the American University of Beirut (AUB) told NOW.

“In particular trailblazers like Joumana set the standard for confronting sectarianism and patriarchy through political representation that aims at rectifying gendered discrimination in the last century,” she added.

Haddad herself strongly believes that running for public office should be regarded as a basic human right, “we should be able to achieve proper gender representation before we can call for any change – the quota is not discriminatory, but a step toward equality.”

According to her, women activists in the political sphere face unique challenges due to persistent gender discrimination and destructive stereotypes.

“Women activists have always shouldered more than their fair share of the burden. They are often subjected to relentless harassment campaigns online and in-person and exposed to specific risks, such as gender-based violence and misogynistic attacks. The parliamentary elections were nothing but a reproduction of the political power itself with the disparity in the distribution,” she added.

Haddad said she did not give up on breaking the glass ceiling. But small steps are sometimes necessary to achieve greater change. In 2019 Haddad founded the youth NGO Freedoms Center, aiming to raise awareness among Lebanese youth on the values of respect, democracy, and human rights.

While planning projects to expose more taboos and empower women in Lebanon, she also mentors young women to become more involved in politics and human rights activism.

For Geha, this is also the only way to move forward.

“Independent female voices and role models are the only way to break the cycle of clientelism and war that defines the Lebanese system,” Geha pointed out.

“Without women on the table, there was no peace after Taif and without independent women in parliament, there will be no moving forward. Lebanon’s version of sectarian state feminism won’t too, independent feminist inclusive leadership will most certainly do,” she added.

Tala Ramadan is a multimedia journalist and head of social media with @NOW_leb. She tweets @TalaRamadan.