On drug trafficking and false narratives: how Lebanon’s drug dealers exploit Palestinian refugee camps to escape the authorities’ control

There is a writing, in one of the alleys of Burj el-Barajneh camp, where the sun never shines, which reads: ‘the drug dealer is a Zionist.’ Let this be a lesson to those who accuse Palestinian refugees, as such, of being the main perpetrators of drug dealing in Lebanon. Or, as we often hear: to take advantage of their own invisibility to enrich themselves from illegal trafficking.

Only because it mainly takes place in the space of the Palestinian camps – twelve official ones, established in the aftermath of the Nakba, between 1948 and 1949, and designed to be temporary, and many other unofficial ones, scattered between the geographies of city suburbs and the history of great caesuras, massacres, wars, exiles – drug trafficking in Lebanon is not a specifically Palestinian phenomenon. With armed groups competing for control, and a limited number of non-governmental organizations working with drug addicts, it is difficult to estimate the prevalence of drug use in refugee camps. However, the latest operations carried out by the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) seem to give an idea of an increasingly frequent issue.

Salim, 34, Palestinian from Yafa and displaced in Beirut for three generations, does not seem surprised by the results of the latest military raid in the Beiruti area of Hangar, surrounding Shatila camp, where on May 16 the army arrested 37 alleged drug traffickers, severely injuring one. “It seems like the usual performance happening at a time when the government is trying to prove its presence,” Salim said.

Footage captured by motorists in the Amal-controlled area showed a substantial deployment of tanks and army vehicles, with an army bulldozer seen demolishing a concrete wall in a narrow alley. According to a military source, the operation led to the seizure of large quantities of cocaine, cannabis, and salvia pills, a hallucinogenic plant, as well as arms and ammunition. The source confirmed that among those arrested were a major drug trafficker in the camp as well as several individuals involved in various types of drug trafficking: the nationalities of those arrested, though, were not disclosed.

“When we read the news of what they described as a massive raid, people in the camp started laughing,” Salim recalls. “Basically, they destroyed a wall, took a picture of it, then left.” The wall he mentioned, on the border area between Shatila and Hangar – the same one whose destruction was captured by a video circulating online – no one knows who owns it, apparently. “The army keeps on destroying it, until someone else, not from the camp, invests in the building, never for longer than two or three years.” According to Salim, “through the military, the government wants to show it is strong for the Lebanese people. But we, Palestinians in Shatila and other neglected areas of the city, know very well where the drug comes from: the Beqaa valley. I wonder how it is able to reach the south of Beirut without being stopped, if not with a certain degree of connivance of the authorities themselves.”

Spaces of exception

Listening to Salim, it is surprising that the way in which one comes into contact with drugs, in the exceptional spaces of the Palestinian camps in Lebanon, is extremely passive, inertial, almost an obligatory passage. “In a square kilometer of extension, it is difficult to imagine not coming across them even once.” He admits that the first time he saw a bag of cocaine, when he was nine or ten, he wasn’t even aware of it. “In exchange for a cigarette or a few lira, they asked me to carry a sealed package from point A to point B. And so it was the second, the third time. Easy money, for expendable lives.” Once he returned to Shatila, he would be safe: or rather, so he believed.

According to official figures, Lebanon hosts more than 470,000 Palestinian refugees, over 50 percent of whom live in UNRWA’s twelve official refugee camps. Legal restrictions prohibit them from being able to pursue Lebanese citizenship, inherit property, and practice about thirty different professions. Not only are Palestinians excluded from social and political opportunities, but since the 1969 Cairo agreement, refugee camps have been placed outside Lebanese governance and under the quasi-authority of Palestinian factions. Drug traffickers and dealers, therefore, often seek cover in these camps, as the Lebanese Army is not allowed to operate within them, and security is maintained by Palestinian factions.

The Lebanese government’s treatment of Palestinian camps changed over time. Until 1958, refugees were mostly welcomed by the population, who viewed their displacement as temporary. Following the Lebanese turmoil of 1958, however, President Fouad Chehab used the Army’s Intelligence Bureau – also known as the Deuxième Bureau – as well as the police, to control the camps, so that for about ten years, until the uprisings of 1969, Palestinians in Lebanon were severely restricted in all aspects of life. They needed permits to visit other camps; meetings of nondomestic nature were not allowed, listening to the radio or reading the newspaper was forbidden, and building or repairing homes required a permit that was impossible to obtain. There were no private bathrooms or drainage systems and everyone, whether young or old, male or female, had to walk, night and day, to reach public latrines. Added to these practices were the daily harassments, humiliations, extortions, arrests, and sometimes torture at the hands of police officers.

In an unplanned revolt in 1969, residents across all camps chased out the much-hated Deuxième Bureau. These mass uprisings across Lebanon’s camps led to the signing of the Cairo Agreement in 1969 between Yasser Arafat, who had been just elected chair of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), and the Lebanese army commander. The agreement granted Palestinians the right to manage their own camps and to engage in armed struggle in coordination with the Lebanese army.

Since then, and through the tumultuous years of the Lebanese civil war, refugee camps became the stronghold of Palestinian resistance movements and the center of their military operations against Israel: at the same time, though, Palestinian-Lebanese tensions worsened drastically, with right-wing Christian militias posing another threat for their survival – as massacres like those o Tal al-Zaatar and of Sabra and Shatila demonstrated -, and later on, during the 2007 siege of Nahr al-Bared camp, with the rise of Islamist political factions, as well as, more recently, with the eruption of intra-Palestinian violence in the southern camp of Ain al-Hilweh.

Drug trafficking is therefore only one of the exceptional aspects of life made possible by the suspension of law in the camps’ areas. The boundaries around them are ideal for the spread of illegal activities, carried out by both Palestinian refugees and Lebanese nationals: yet wrongly perceived as mainly linked to the former ones. When the space of the camp overlaps with that of the city – like in the belt neighborhood of Hangar -, and that of exceptionality with the rule of law; when outcasts meet citizens – a new dimension is produced: that of invisible border areas, that outlaws can easily take advantage of.

And while drug dealers capitalize on Palestinian invisibility, to pay the highest price of drug spreading are the refugees themselves – captured, in the absence of any regulations, in the spiral of addiction and its criminalization. As Lebanese law criminalizes drug abusers, in fact, and all hospitals are required to call the police to report anyone who has overdosed, the implications for those needing life saving assistance are extremely negative.

Moreover, since Palestinians only have access to primary healthcare from the United Nations’ Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), in case of overdose they must travel to hospitals outside the camps: and with strong stigmas on Palestinians still prevailing, human-rights groups say they have a difficult time breaching the topic of drug addiction in the camps. With all the discrimination Palestinians face in Lebanon, drug usage and consequent negligence from care risk to be underestimated.

A center for the people

Markaz al-Insan, the center of the people, in the Palestinian refugee camp of Burj el-Barajneh. Photo credit: Ahmad Abu Salem

At thirty-one, Jihad carries the strength of three men together: the one who suffered from drug addiction; the one who survived the shipwreck in Tripoli in April, 2022; the one who is reacting to the two traumas with a courageous smile and the desire to get up.

Yet he is only a young man. Palestinian, he was born and raised in the refugee camp of Burj el-Barajneh, south of Beirut. He’s been on drugs for fifteen years, he says, but with periods on and off. For drug-addicts he uses the word yta‘ata, three syllables of stigma in his community. He used to take drugs when sad, when in love, when bored: and he started, like many others, due to the negligence and the excess of freedom of those only children who live, without responsibility, in the shadow of busy parents. Hidden. Lonely. Spoiled. And like many others he became extremely skilled at lying, so when the effect of smoking first, and then of cocaine, appeared evident, he pretended to be drunk and went into hiding thinking about how easy it is to fake a smile when no one asks how you feel.

Nimer is the first, in fifteen years of illness, to have asked him how-are-you without accepting a ‘fine’ as an answer. Palestinian born in Yarmouk camp, in Syria, and now displaced in Burj el-Barajneh, in 2013 Namer founded Markaz al-Insan, literally ‘the center of the people,’ a completely free-of-charge support structure for those suffering from drug addiction and based on an approach that to medicines prefers listening, awareness and art therapy. And that, to the word ‘drug addict,’ contrasts ‘sick,’ in Arabic marid, to free with the language of inclusion from the burden of stigmatization.

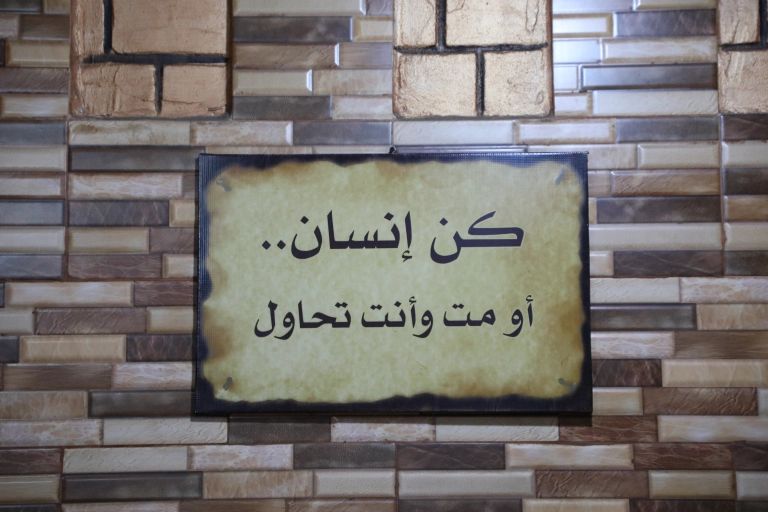

A writing on the wall of the center reading: “Be a human or die while you’re trying to”. Photo credit: Ahmad Abu Salem

“At first I didn’t think I could quit drugs without medical treatment. Ma’assalame, I told him, and I let it go,” Jihad admits. And Nimer, standing in the doorway listening, doesn’t seem surprised. Men like Jihad are used to believing that addiction is a mental illness because these are the means by which the health system in Lebanon has been able to react to their suffering: boxing them into a category that does not represent their pain, majnunin – the crazy ones; interned them for a couple of weeks under the effect of sleeping pills; then abandoning them, again, to solitude and invisibility.

Nimer, who seems to know deeply about unheard suffering, not only asks his boys how they are without-accepting-a-’fine’-as-answer: but also why they started – deeply convinced that education to feelings, to one’s knowledge of pain, may be the only dignified means – the only human means – of finding the way out of the darkness, and not being swallowed up.

Today, Jihad speaks openly about his story in a dimly lit room in the camp of Burj el-Barajneh. He appears confident and his voice never trembles – except when street noise forces us to interrupt the interview, and he takes the opportunity to make sure that the answers are up to par. He doesn’t even falter when he mentions his father’s illness; nor when he talks about the twenty-seven kilos lost through carelessness; not even when he remembers the shipwreck off the coast of Tripoli, the reasons for such a crazy gesture, the desperation of those who believe that running away is the solution to pain, and as a destination has a foreign word that sounds like Europe. And think that well-being will come only if far away from here.

Having narrowly escaped death, he took drugs again. “To celebrate,” he says: to exorcise fear. To curse extinction. He could not imagine that his starting point could have been the dark and noisy room of a refugee camp on the outskirts of Beirut. All around wooden objects that recall resistance, philosophical thought, faith, and Palestine – although the center, completely free of charge, is also visited by Lebanese and Syrians. Palestine is present but in the background, as a warning to reaction and non-alienation.

What prompted him to take that boat, Jihad seems to know and is not afraid to admit it: it is the same blindness that convinced him to try the first pill, now more than fifteen years ago. Both times, he was facing the sea: and both times he had the impression of being a champion. Swimming, he felt like a hero. By surviving, he convinced himself of his own courage. Falling back into addiction, he ignored the fear of failing and surrendered to a life – or rather a survival – in fits and starts, not defended but repudiated between one dose and another.

Yet, since he has re-learned how to speak, how to voice his emotions, Jihad loves more: and with new awareness. Today he also knows the meaning of a dream of departure that is not one of escape – since together with the hope of change he carries himself, and it is not to Europe he aspires to: but to feel good, once and for all.