The night of Quneitra in the lens of Mohammad Malas

In the second feature film directed by Mohammad Malas, Al-Leil, The Night (1992), co-written by Ossama Mohammed, the house – a metaphor for Syria – has fragile walls and mediocre guardians. A diptych that focuses on the empty center of fatherhood – replaced by a grotesque authoritarian drift; on the distortions of a conservative and religious society; on the impotence to transform the state of things attempted by civilians: the men and women of Al-Leil, whose utopias of revolution are dissolved in the tragedy of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Al-Leil retraces several decades of Syrian and Palestinian history, confining its lens within the walls of the town – ghost since 1974 – of Quneitra. Bordering on the Golan Heights, occupied by the Israeli forces in June 10, 1967 – the last day of the Six Days War -, briefly recaptured by Syria during the 1973 Yom Kippur War before its control being regained by Israel’s counter-offensive, the village – where Malas was born – was restituted to Syria in 1994, completely destroyed.

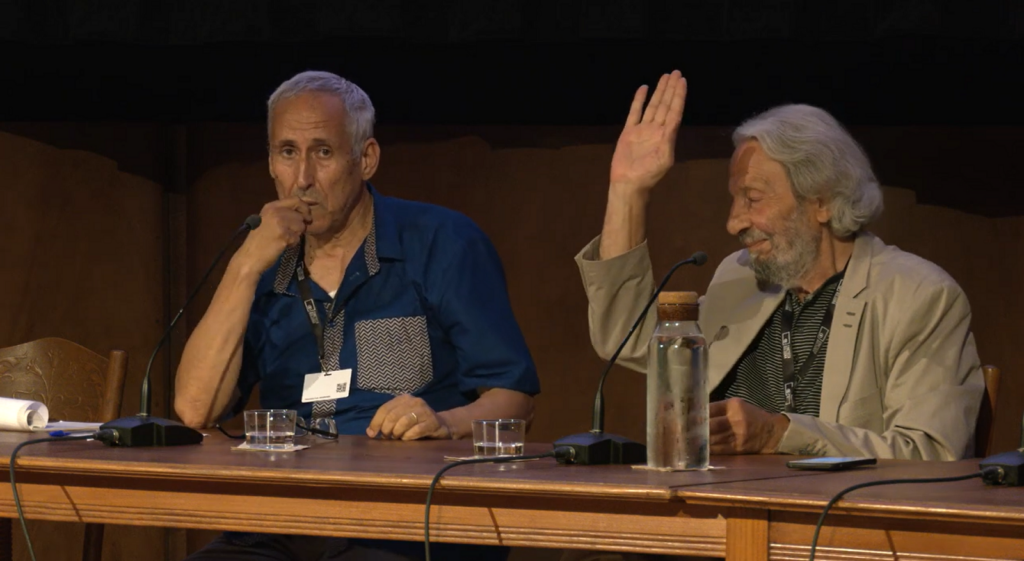

Mohammad Malas and Mohamed Challouf at the Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna, Italy, on June 28, 2024. Photo credit: Valeria Rando

We are led to the grave of the filmmaker’s father, an old Syrian fighter who joined the volunteer armies in Palestine in the Great Revolt of 1936. Trying to exorcise the feeling of shame and humiliation that have long accompanied the image of the father and the village, Malas stages a poetic dialogue with the mother to evoke the spectrum of the lost town and “imagining another death of the father,” as declared by the director himself. But tracing the outline of a memory tortured by burning questions finds only bitter answers.

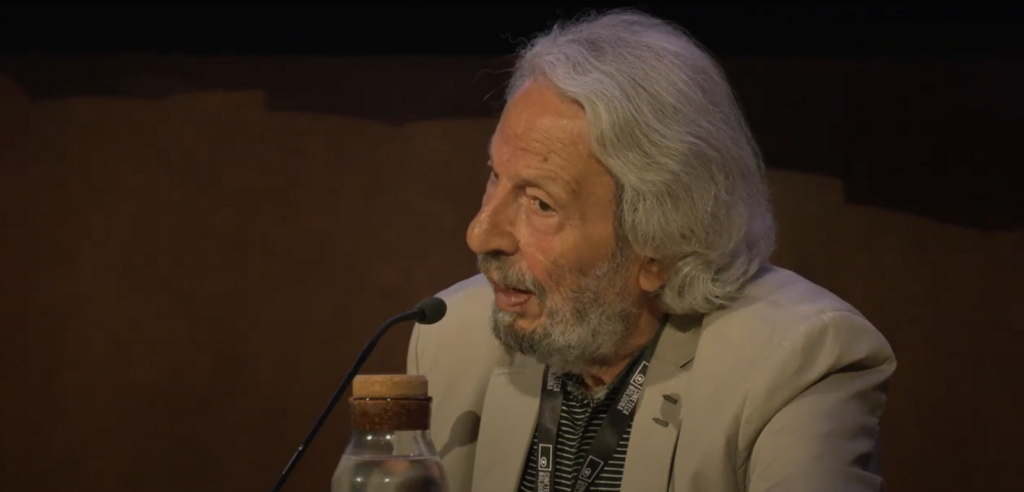

Mohammad Malas at the Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna, Italy, on June 28, 2024. Photo credit: Valeria Rando

Like a breach from the crack of a broken glass, the voice-over materializes glimpses of everyday life in strategic points of the national history, from the protests of 1936 to the coup of 1963. Yet, the temporal leaps are never made explicit and indeed flow fluidly in parallel with the dialoguing voice that makes apparent what the historical reconstruction does not show: the absence of the father. A city of women, children, common people, where soldiers are nothing but an elusive presence. Engaged far from home, against the English occupation in Palestine, they appear in the city only to take a photo, the only means of testimony of their actual existence, before Malas’ camera arrives to restore depth, even if starting from their absence, to these forgotten lives. Then, he turns to the memories of his own childhood.

Shots from Mohammad Malas’ Al-Leil (1992). Source: Tumblr

The opening act

For the generation of cinephiles “of before” – that of the 1980s – says the Tunisian director and producer Mohamed Challouf on the stage of a crowded cinema in Bologna, Italy, “there were three or four things from the Arab world that we were proud of in Africa.” And he lists: the creation of the Carthage Festival in 1966, the first showcase dedicated to the promotion of Arab-African cinema; the foundation, in 1969, of the Ouagadougou Pan-African Film Festival; the opening of the Algiers Film Library; and a trio from the Syrian cinema scene – three chosen, elective brothers, mutually supportive filmmakers, who took the destiny of their country’s cinema into their own hands after years of commercial films that merely imitated old Egyptian ones. They were Omar Amiralay, Ossama Mohammed, and Mohammad Malas – the last of whom, sitting next to Challouf, arrived in Italy from Damascus to present the newly-restored version of Al-Leil, at the Festival del Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna.

“In its early days, Syrian cinema was nothing more than an imitation of Egyptian commercial cinema. When the Baath party took power in the late 1960s, it created Al-Muassassah al-Ammah li al-Sinema, or the National Film Organization, an independent arm of the Ministry of Cinema established to oversee the production, export and import of Syrian films. In that period many important films were made, and many young people were sent abroad to study cinema, in Eastern and Western Europe, or in Russia,” says Malas – unfolding the plots of a story that concerned him personally, having studied in Moscow, like many of his colleagues who preceded him: Arab directors whose realistic gaze, entrusted to the camera, marked the starting point – for the generation of Malas, Amiralay and Mohammed – to imagine a different cinema. A new cinema. For example, the film The Dupes (1973), by the Egyptian director Taufiq Saleh, based on a short story by the Palestinian writer Ghassan Kanafani; the experimental Al-Yazerli (1974) by Qais al-Zoubaidi, Iraqi; the Lebanese director Borhane Alaouié, with his Kafr Qasim (1975), on the Palestinian cause; or Al-Sikkin, The Knife (1972), by the Syrian Khaled Hamada.

“When the new generation, mine, arrived, we thought about making films on the socio-political reality of Syria at the time. It was the beginning of Syrian neorealism. A legend of this politically-engaged Syrian cinema, founded by Amiralay, was the film Everyday Life in a Syrian Village (1975).” That was the reference that created the hummus for the development of friendships, dialogues and connections between these filmmakers – despite the production remaining under the control of the Syrian National Film Organization.

Malas worked as a school teacher between 1965 and 1968 before moving to Moscow to study filmmaking at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography (VGIK). After his return to Syria, he started working at the Syrian Television, where he produced several short films including Quneitra 74, in 1974, and al-Zhakira, The Memory, in 1977.

“Eleven years after graduating from the Institute in Moscow I made my first feature film, Ahlam al-Madina, Dreams of the City (1983), which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. The international and local success of this film – very rare for external and internal consensus to be achieved at the same time in the Syrian context – allowed me to gather courage to make my second feature film in the current of politically-engaged Syrian cinema. In the meantime, the director Ossama Mohammed returned to the country, having attended the same school in Moscow, guided by the same teachers that I had also had. Between the three of us, Omar, Ossama and I, a bond flourished beyond collaboration: complicity underpinned each of the films we made.”

The three directors, together, made two documentaries. The collective project involved creating portraits of ten forgotten cultural political figures in Syria. Unfortunately, they only managed to make two: Light and Shadows (1994), a portrait of a pioneer of Syrian cinema who made the first Syrian films as a producer and studio owner; and Moudaress (1966), about the Syrian pioneer painter Fateh Moudarres.

They continued until 1992 when Malas made his second feature-length film, Al-Leil, The Night, and Ossama Mohammed released his Nujum Al-Nahar, Stars in Broad Daylight (1988).

“My cinematic generation didn’t just come up with a topic or address an issue, but I can safely state that we managed to establish our own language. And this wasn’t a traditional language,” Malas says. “With Al-Leil I had an opportunity to lay the foundation for a structure that was entirely mine. I dedicated twenty years of my life to talking about this ancestral home of mine, Quneitra, with all its nightmares and dreams, with every vision that I developed into film, and carried from one film to another, with the purpose of composing a visual, sentimental and personal work.” That was, as Russian director Andrej Tarkovsky would have called it, a carving of history; a search for time from a personal perspective, not just a historical one. And he continues: “to me, the time of that vague love for the ancestral home, towards the mother and the lost father, and to the political era, which is also lost, or Quneitra in Al-Leil – all of this is an attempt to express that pain, that loss, which pierces your connection to reality with the peculiar flavours of alienation and longing.”

Shots from Mohammad Malas’ Al-Leil (1992). Source: Addiction Cinema

Chronicles of a lost country

Before making films, Mohammad Malas wanted to be a writer. He ended up working in cinema without having chosen it, almost by chance. “I spent my childhood on the streets, after my father’s death, and the desire to better understand Syrian society and defend the condition of the weakest developed in my mind. After studying cinema, I cultivated the desire of mixing literature and film, poetic dimensions and visual dimensions. The Night bears the mark of this synergy.”

And if Dreams of the City tells of the lost democracy that Syria experienced in the years before the change of power – Al-Leil aims to paint the lost place of the hometown, Quneitra, occupied by the Israeli forces in 1967, and returned to the Syrian regime completely destroyed seven years later, in 1974. “It was a tribute to the village of my birth, to which I also dedicated a book,” he says before the screening, in the room which also hosts the director and friend Ossama Mohammed – and the memory of the great absentee, Omar Amiralay.

As the political changes flash by in rapid succession – the French occupation, the Second World War, the independence of Syria, the British Mandate – the son comes to realise that the legend he had created, that his father perished fighting the foreign enemy – the Jews -, conceals quite another reality. The lost father, Alallah, who has twice fought in Palestine, had challenged the Syrian government’s hollow declarations of support for its liberation. He died after being beaten up by the secret police. “In the end, there are only fragments of memory,” says the son: and Al-Leil pieces them together using a visual language of extraordinary potency, combining a range of universal metaphors with intimate human portraits. An arranged marriage that becomes a union of love, the world of a little boy who dreams of emulating his militant father, the enclosed kitchen existence of the veiled women, the everyday life and fortunes of a city and its people.

In Malas’ eyes, cinema is powerful enough to re-imagine history, to recreate it for those who were not there to see. “I’ve experienced things and places that are no longer there, no longer visually accessible; but in my head they are so vivid and I want to share them with the world. As a filmmaker, I see this as a responsibility; a calling.” In the film, Malas brings Quneitra back to life through a young man searching for answers about the life of his rebellious father, who inhabited the village in the 1930s and 1940s. “The occupation destroyed the village; but cinema managed to rebuild it,” Malas muses.

This, precisely, is what Malas sought to achieve with his renowned trilogy, beginning with Dreams of the City in 1984 and ending with Ladder to Damascus, in 2013, where he attempts to chronicle the last fifty years of modern Syrian history. “I wanted to complete the two films with a trilogy: after the lost time – democracy; the lost place – Quneitra; the lost Syrian being, the human Syrian being, that has been forgotten. But the Film Organization prevented me from realizing it. So I made Ladder to Damascus.”

After the outbreak of the war in 2011, the regime stated that in Syria there would have been no more space for culture. Power – and the blind support for power – became the only position possible: without it, artists and intellectuals lost their right of expression. In 2013, thanks to the help of a Lebanese production company – the Abbout Productions, founded by Georges Schoucair – he could finally realize his third feature-length film, Sulam Ila Dimashq, Ladder to Damascus.

“At this point I no longer had the opportunity to shoot outside my house. The streets stopped being public. So I shot the film entirely inside my apartment. At the end of the film, the actors climb the ladder leading to the roof, discover the city, and start shouting freedom, freedom.”

Yet the film – just as the previous ones – does not aim at restoring heroism to forgotten heroes, far from it: with humility and eloquence, it gives the tragedy of Syria and its struggles for liberation the face of a peasant, the figure of a man, his wife and his son, a group of young people living in a struggling director’s house. The loss of their memories and biographies represents an erasure from the script of official history, often self-congratulating and triumphalist, that citizens like Malas – before being artists – fight against.

The threat of a free Syrian cinema

The National Film Organization started to sense the subversive threat of Malas’ cinema – as well as that of his elective brothers, Amiralay and Mohammed – and began to strangle their intuitions under its strict control. In 1992, after the national production of the film, Malas did not manage anymore to realize a project through the support of the Organization. There was a reputation among intellectuals for him being against the regime. Therefore, forced to look outside for the production of his films, Malas resorted to alternative methods of bringing them to the light, seeking funds and independent production in the Arab world and beyond.

“But cinema has always suffered in Syria, even before the outbreak of the current events,” Malas says. “The state has always enjoyed a complete monopoly of film production and distribution, which compromises the honesty and the freedom with which films are made. Even now, after everything that’s happened, this is still the case.” Even when independently produced, in fact, films still have to be approved by censors. Elaborating, he continues, “it doesn’t really make a difference whether your film is released in Syria or not, because people no longer go to the movies anyway. The theatres are in poor condition, the projectors are in bad shape; the sound and image quality of the films shown is often disastrous.”

Yet, for Malas himself, leaving Syria is not an option – so far, at least. He wants to stay in his city, even if it’s no longer safe. Faced with an ailing industry, Malas is still driven by a burning passion to make films, stemming from his own stories and the desire to tell them. His cinema heavily bears the imprint of his childhood and adolescence, with the personal and the political invariably intertwined in his work. For someone whose cinema is as personal and as place-centred as his, staying in Damascus is also a matter of artistic survival – of a tight bond to the land that crosses the creative process and blossoms in the beauty of his shootings. No matter how sad they might look like, how crumbling the walls of the house are. A homeland is a homeland.