Lebanon's newly appointed Central Bank governor, finds himself navigating a complex and contentious landscape as the country grapples with banking secrecy reforms and financial sector restructuring. Karim Souaid, Lebanon's Central Bank governor, has reportedly been sidelined in the decision-making process surrounding recent financial reforms. Despite his pivotal role in overseeing the country's monetary policies and banking sector, key amendments—such as those to the banking secrecy law and the proposed restructuring measures—were advanced without his full involvement or consultation. This exclusion raises concerns about the transparency and inclusivity of the reform process, particularly as Lebanon faces mounting pressure to meet IMF requirements. Souaid's absence from these critical discussions not only undermines his authority but also casts doubt on the coherence and effectiveness of the government's approach to financial recovery.

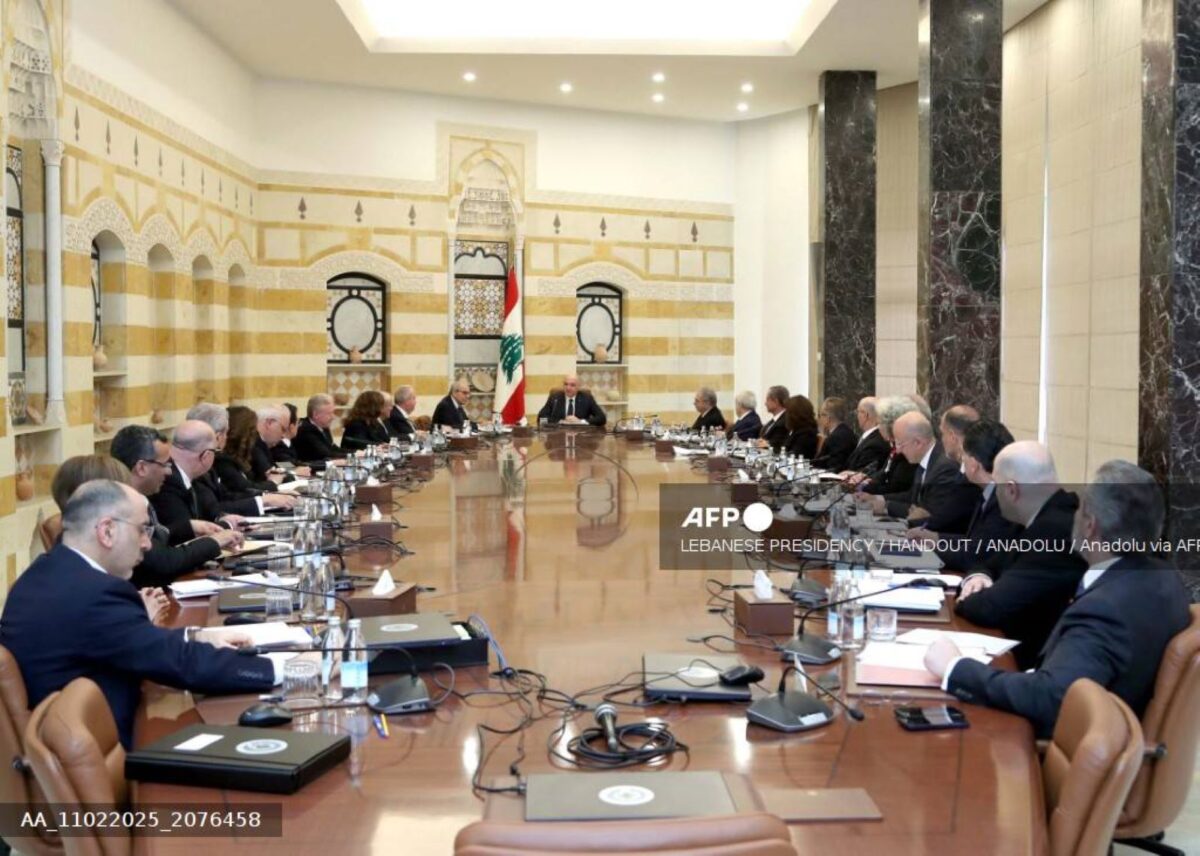

Amidst more controversial positions from government members the council of minsters is seeking to ratify the banking secrecy law which aim is to increase transparency by revealing retroactively ( 10 years?) banking account holders’ names and transactions . The council of ministers has reportedly ratified the law and sent to the parliament. The timing of these

amendments is strategic, as Lebanon prepares for upcoming IMF meetings. The government hopes to demonstrate progress on reforms to secure further support and funding. The IMF has made 45 meetings with the former government for the reform, no advancement has been reported.

The government is expected this week also to ratify the “Restructuration of Banking Deposits and Restructuring the Financial Sector” initiative designed to find a solution to the depositors billions “hostaged” by the banking sector.

Souaid under fire

The move is seen “suspicious” and “hasty” without consultation with the new appointed governor, Karim Souaid to the Central Bank of Lebanon, downplaying his role in having a say in the new restructuration process. Is the Nawaf government seeking to impose a blue print of reforms on Souaid? Lebanon’s newly appointed Central Bank governor, finds himself navigating a complex and contentious landscape as the country grapples with banking secrecy reforms and financial sector restructuring. To be noted is prime minister Nawaf Salam and seven of his appointed ministers have not endorsed Souaid for his nomination. Karim Souaid, Lebanon’s Central Bank governor, has reportedly been sidelined in the decision-making process surrounding recent financial reforms. Despite his pivotal role in overseeing the country’s monetary policies and banking sector, key amendments—such as those to the banking secrecy law and the proposed restructuring measures—were advanced without his full involvement or consultation. This exclusion raises concerns about the transparency and inclusivity of the reform process, particularly as Lebanon faces mounting pressure to meet IMF requirements.

Souaid’s absence from these critical discussions not only undermines his authority but also casts doubt on the coherence and effectiveness of the government’s approach to financial recovery.

Lebanon’s banking secrecy laws, once a cornerstone of its financial system, have come under scrutiny as the IMF demands greater transparency. The recent amendments aim to ease confidentiality restrictions, enabling government agencies to access banking information for oversight and combating financial crimes. However, these changes have sparked debates over data protection and the potential misuse of sensitive information.

Souaid knows that the restructuring of Lebanon’s banking sector remains fraught with challenges. Disagreements over the allocation of financial losses and the repayment of depositors have stalled progress will certainly be a major corner stone of his career. The proposed banking sector restructuring law, which is critical for restoring confidence in the financial system, has faced repeated delays due to political and institutional deadlock. With the IMF meetings in April and June fast approaching, Lebanon’s government is under pressure to demonstrate progress on financial reforms. This urgency has led to a series of rushed initiatives, including amendments to the banking secrecy law and the introduction of the banking sector restructuring law. Critics argue that these measures lack a comprehensive approach and risk exacerbating the country’s financial woes. Souaid’s role as Central Bank governor is crucial in this context. His ability to navigate these reforms, address the depositors’ crisis, and implement transparent policies will be key to Lebanon’s negotiations with the IMF. However, the political standoff and lobbying efforts by influential groups add another layer of complexity to his mission.

More political Controversy?

A source which claimed anonymity say that the current laws were raised during the recent IMF meetings in Lebanon; however, those plan will create a big political controversy in Lebanon.

The move also is a new regeneration of the banking leadership, the source believe. The IMF will have a look at all the banking accounts ins and outs of the system from 2019, the source explained. The new laws include restructuring Lebanon’s banking sector, implementing a medium-term fiscal and debt restructuring strategy, auditing the Central Bank’s (BDL) foreign assets, conducting an external evaluation of the country’s 14 largest banks, and unifying exchange rates, among other priorities. Another IMF reform must-do prerogatives.

The need to create a new banks licenses is also on the burner. Are all those laws will create a healthy banking system the source asked. Another controversy erupts from the fact that the Banking Control Commission can have a say in overlooking banking accounts over a retroactive period. The source asked : “ on what benchmarks and grounds”?

The opposition to reforms comes from ?

As the government sought to implement its recovery plan, Lebanese bankers and elites undermined efforts by presenting misleading narratives to various stakeholders. They depicted reforms as politically motivated, sowing confusion and resistance. The banking sector even proposed its own restructuring plan, which included transferring public assets to the banks, freezing deposits for extended periods, and rejecting the restructuring of lira-denominated debt. This plan was fundamentally flawed, failing to address systemic imbalances or attract fresh dollars into the economy, and was swiftly dismissed by international counterparts.

Controversial aspects of the plan are also tied up to the proposed amendments to the banking secrecy law and multiple revisions to the capital control law, aimed at facilitating the recovery of the financial sector. At its core, the repayment process for depositors must be grounded in a transparent and comprehensive assessment of the banking sector’s current financial health— specifically, understanding how much banks currently hold and owe. However, attempts to enforce transparent auditing have been met with resistance from the Association of Banks in Lebanon (ABL), delaying progress.

Lifting banking secrecy for ???

Both projects underline the lack of data protection measures and safeguards against misuse or blackmail which poses significant risks, undermining public trust. IMF’s Reform Demands: The IMF has made the modification of Lebanon’s banking secrecy law a key condition for financial assistance. This aligns with the Fund’s broader push for transparency and accountability in global financial systems. There is also an urgency to ratify laws and make appointments before the IMF meetings in April and June suggests a reactive rather than proactive approach. This strategy risks prioritizing short-term gains over long-term stability especially in government agencies thus by granting them access to banking information! Still to be seen if those amendments aim to combat financial crimes, money laundering, and terrorism financing or seek to replace the old junta with a new one.

Restructuring Lebanon’s banking system is not seen just as enabling authorities to evaluate banks’ viability and oversee the recovery process. Sources wonder if this is a critical step in addressing the financial gap and stabilizing the economy or introducing new banks in the system. The upcoming proposal for a bank restructuring law is shrouded in uncertainty, experts believe. Key issues, such as the distribution of responsibilities between the state, banks, and the Central Bank, as well as the fate of deposits, remain unaddressed. This lack of clarity could lead to further instability in the banking sector. On October 18, 2022, Lebanon’s Parliament passed a pivotal amendment to the banking secrecy law, designed to remove barriers and empower key government institutions—including the tax authority, judiciary, Banking Control Commission, and Central Bank—to access banking information. This marked a significant departure from the longstanding banking secrecy practices that had formed the backbone of Lebanon’s economic model. The origins of Lebanon’s banking secrecy trace back to September 3, 1956, when a special law barred Lebanese banks from disclosing their clients’ identities, accounts, and activities—even to government entities. Violators faced penalties ranging from three months to a year in prison.

While banking secrecy once facilitated foreign investment and bolstered Lebanon’s economy, its framework also encouraged governments to overborrow from the banking sector to cover budget deficits. By the mid-2010s, however, international agreements began limiting Lebanon’s ability to shield deposits from foreign scrutiny, curbing the allure of banking secrecy. The financial collapse of 2019 further eroded its utility. As Lebanon faced mounting crises, the IMF insisted on lifting banking secrecy as part of a broader recovery strategy. This reform was vital to promoting transparency, combating financial crimes, and enabling oversight of the failing banking sector. The claim of a premeditated plan to target depositors, write off deposits, and replace old banks with new ones is alarming. If true, this strategy could undermine the banking sector, erode public trust, and concentrate power within specific groups. The move is not healthy and is an introduction to a new quiproquo in the socio-economic system, the source say. Why does the IMF imposing such controversial divergent reforms is hard on Lebanon as billions were given to other countries?, the source remarked.

Banks shady debt figures

Up on the controversy are figures of Lebanon banks debt volume and whereabouts. For example, there is no accountability on volumes of issued Lebanon banks’ preferred shares and why are they classified as tier one capital debt instruments in their balance sheets, the source quoted. According to NOWLEBANON’s investigation most alpha banks have made more than 7 issues of preferred shares amounting to Usd4 billion and were not paid and still without provisions. Lebanese banks, such as Byblos Bank, have issued multiple series of preferred shares. For example, Byblos Bank’s Series 2008 and 2009 Preferred Shares were issued at $100 per share, offering non-cumulative annual dividends of $8 per share. Byblos Bank’s preferred shares represent a small fraction of its total capital, with 2 million shares issued in each series.

Analytically the restructuration plan proposes that big depositors are said to be part of the new core capital of banks meaning that their positions will be diluted in the new endeavor.

According to the same source, there are Usd3bln injected in the system are still not accountable for adding to 60pct of capital in foreign currency . Those were invested in the BDL.

In short the new restructuration plan fails on the accountability of the banks managers. There is a need to dissolve the old banking system, the expert believes.

The source remarked also that the shady role of the auditors is not accounted for. “They were either improvising or compromising in auditing banks” the source say. Without completing the audit, accurately determining a payout cap remains impossible. Current estimates, however, suggest that the liquid reserves of both commercial banks and the Central Bank fall short of covering the $100,000 payout cap proposed by the Lebanese government. Furthermore, it is increasingly apparent that this potential payout cap may decrease over time.

Statistics reveal that approximately 1.3 million account holders—representing nearly 94 percent of all accounts—have less than $200,000 in deposits, accounting for only 30 percent of the total deposit value. Conversely, the remaining 70 percent of deposits, valued at $65.54 billion, are concentrated in just 87,000 accounts.

No Reform in sight

The move to restructure banking laws comes conjointly to the annulment of the Previous Recovery Plan initially drafted by Lazard consultancy form. The State Council’s decision to annul the previous government’s recovery plan has left a significant void. Without an alternative plan, negotiations with the IMF are stalled. This lack of direction exacerbates the economic crisis, as no comprehensive framework exists to address the financial gap or propose necessary reforms. The new government has not stepped up to fill this void. The absence of a recovery plan means there’s no roadmap for economic stabilization or reform, leaving the country in a precarious position. Figures like Amer Bsat and Nawaf Salam, along with “Kulluna Irada,” activists are reportedly pushing fragmented laws through the Cabinet and Parliament. This piecemeal approach lacks the coherence and negotiation needed for a comprehensive recovery strategy, raising concerns about its effectiveness and transparency. The previous beneficiaries of banking secrecy included banks implicated in depositors’ losses, tax evaders, and high-ranking officials accused of illicit enrichment. Given the influence these groups wield within Lebanon’s political and financial systems, the passage of these amendments required considerable pressure from the IMF.

The question remains whether the judiciary will therefore be able to lift banking secrecy by seeking information directly from the banks without the need to go through any other administrative body, in accordance with the revisions. The local tax authorities will also be able to check for tax evasion by correlating the statements they receive with information from bank accounts. Thus, the mass of losses within the banking sector altogether accumulated out of the limelight between 2011 and 2019, where this amount represent the difference between the sector’s obligations towards depositors in foreign currencies and the remaining dollars in the banking sector which were squandered in the operations of financing the fixed exchange rate. The acceleration of the accumulation of losses occurred specifically between 2015 and 2019 when the deficit in the Central Bank’s net foreign reserves increased from $1.9 billion in 2015 to more than $55.5 billion in 2019. That deficit represents the difference between the obligations and assets of the Central Bank in foreign currencies, and it is precisely the size of the losses that affected depositors’ money in banks, which were deposited in the Central Bank.

Overall, these amendments are not “perfect” as they contain numerous loopholes that undermine the efficiency of the legislation. They include restrictions on the judiciary’s ability to access information in situations in which a lawsuit has been filed rather than during initial investigations that precede filing a lawsuit. While the remaining gaps can be addressed gradually down the line, the approved amendments do indicate relative progress in terms of financial transparency – a development that is urgently needed in Lebanon.

More déjà vu measures, Transition to a New Corrupt System?

The assertion that a new corrupt system is replacing the old one highlights the cyclical nature of governance issues in Lebanon. Without systemic reforms, the country risks perpetuating the same problems under a different guise.

In April 2020, the government, in collaboration with advisors from Lazard, introduced a recovery plan that addressed the core issues. This comprehensive strategy included restructuring debt and the banking sector, reforming public finances, implementing social safety nets, and fostering economic growth. The plan was widely praised by international organizations like the IMF and World Bank for its candid acknowledgment of systemic losses and its roadmap for reform. However, the magnitude of the losses—exceeding USD 60 billion by 2021— highlighted the extensive damage to Lebanon’s economy and the bankruptcy of most commercial banks. The crisis exposed the central bank’s alarming practices, including the concealment of losses under “other assets” in its balance sheet. Still those irregularities are still not accounted for. By 2017, Lebanon’s banking system had liquid liabilities amounting to 259% of GDP, while bank assets stood at 161% of GDP. These figures underscored the system’s over-leverage and vulnerability. Between 2000 and 2019, financial system deposits consistently exceeded 200% of GDP, peaking at 250% in 20171. The central bank’s losses, equivalent to Lebanon’s GDP at its peak, rendered the commercial banks incapable of retrieving their deposits, leaving the public without access to their savings. Banking secrecy laws further compounded the issue, enabling the smuggling of funds abroad by powerful figures and creating a trust deficit among depositors. Lebanon’s consolidated balance sheets revealed troubling trends over the years. By 2018, claims on the public sector by commercial banks had reached LBP 46,779 billion, a significant increase from earlier years. Similarly, claims on the resident private sector stood at LBP 81,037 billion, reflecting the growing exposure of banks to domestic risks1. Foreign currency deposits accounted for a substantial portion of liabilities, highlighting the reliance on external inflows to sustain the system. These figures painted a picture of a financial sector heavily dependent on unsustainable practices, with mounting liabilities and limited assets to back them.

Lebanon elites fear that the refusal to engage in genuine reform reflects the desperation of Lebanon’s elite to preserve their privileges and prevent meaningful change. The system’s interconnected clans resisted all efforts to dismantle the entrenched corruption, leaving the nation trapped in an ill-fated cycle of economic instability.

Lebanon’s path forward requires a bold departure from this legacy, with transparent reforms and accountability at its heart. Only then can the country hope to rebuild trust, revive its economy, and offer its citizens a future free from the burdens of systemic failure.

Maan Barazy is an economist and founder and president of the National Council of Entrepreneurship and Innovation. He tweets @maanbarazy

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW