The latest Israeli call for evacuation of all residents of Baalbek pose another threat to the future of Lebanon: this time, to one of the country’s most precious archaeological sites

What is under attack, this time, is not strictly political. It is not factious, nor confessional. And above all, it is not rebuildable. The Roman Temple of Baalbek, just one of the countless riches of the Lebanese archaeological heritage, if it dies, will not be celebrated as a martyr – on the one hand – nor blamed for having dragged the country into the abyss of another war – on the other. If history dies, it will leave no one displaced: but orphaned. Of a testimony of the past – a very distant past – which is, in other words, a collective identity.

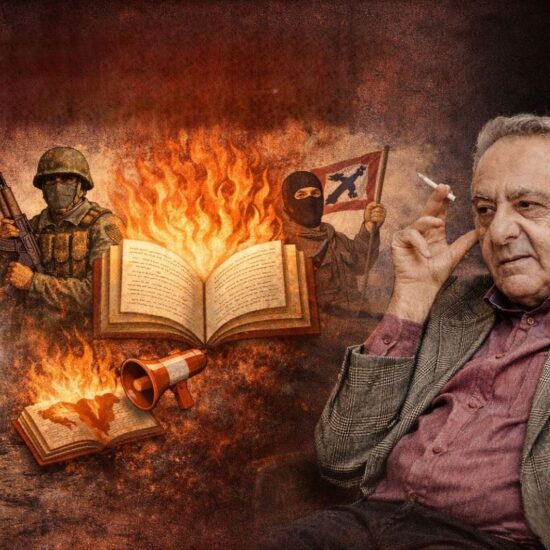

The urgency, the agitated, visibly angry tone of Charles al-Hayek – Lebanese historian, heritage expert, teacher, and founder, among other projects, of the platform ‘Heritage and Roots’ – gives an idea of the gravity of the latest Israeli affront: to the Lebanese people, to international law, and a thousand-year history. “Lebanese, regional, and global history,” al-Hayek emphasizes. The evacuation order imposed on all residents of Baalbek, in the north of the Beqaa Valley, and its surroundings, on Wednesday October 30, followed by a chain of bombings, the massacre of dozens of people, and the displacement of at least 150 thousands, also endangered the complex of Baalbek, its Temple of Jupiter – the largest of the Roman world after the Temple of Venus in Rome – with its colossal structures: one of the finest examples of Imperial Roman architecture at its apogee. And a piece of identity for Lebanese of all times. The third, among the six cultural properties enlisted on Lebanon’s UNESCO World Heritage list, to be located in an affected area, together with Anjar and Tyre, under constant Israeli bombing.

In addition to those six sites – which include also Byblos, the Qadisha Valley and the Forest of the Cedars of God, and the Rachid Karami International Fair of Tripoli -, as a signatory of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property, ratified in 1998, and again in the 1999 Second Protocol, ratified in 2019, Lebanon committed to marking other 22 important sites with a distinctive emblem, known internationally as the Blue Shield. They were set up in partnership with the Ministry of Culture and the Lebanese army, some of whose units received specific training in the protection of cultural property alongside those of UNIFIL. Israel has never ratified the Convention, which partly explains why it has never been punished for damaging several heritage sites in southern Lebanon during the 2006 war.

Among the 22 protected monuments are the very important archaeological and cultural sites in the Beqaa and south Lebanon, such as the prehistoric cave of Adloun, the Phoenician Temple of Sidon, the Phoenician Temple of Kharayeb, Umm el-Amed in Naqoura, the Roman temples of the Beqaa and the Haramoun area, the early mosques and maqamat of the Beqaa and south Lebanon. And more, the Crusaders’ era castles of Beaufort, Tibnine, Shaqra and Chamaa, the Ottoman period markets and houses – like those, razed to the ground, of Nabatieh -, all mentioned by al-Hayek as sites under a real, dangerous threat.

Add to that the invaluable, intangible heritage of the communities of these afflicted areas, represented in their songs, social practices, and culinary heritage, that needs to be documented and protected. “So that when the war ends, it can be a tool to reconnect these communities to their land and reconnect the Lebanese to their history,” he concluded in the video-message shared with NOW Lebanon.

Stripping the Temple

However, last November, after one month since the beginning of the ongoing conflict, Caretaker Culture Minister Mohammad Mortada announced his decision to remove the Blue Shield emblem from the Baalbek Temple complex, raising concern for Lebanon’s most renowned archaeological site. Mortada’s decision, implying abandoning Baalbek’s Roman ruins without legal protection in the case of a potential damage-inducing war – which we are now facing – was justified by proving the inefficiency of that shield, that the atrocities committed in Gaza have proven a failure. In a post published on X on November 2, 2023, he wrote: “What protects Lebanon, its people and its private and public property is our valiant army and the resistance.” A symbolic gesture, yet dangerous: and contradicted by Mortada himself, who urged, on Wednesday, the international community and Lebanon’s permanent representative to UNESCO in Paris to prevent Israeli attacks on the same site that his decision, one year ago, contributed in stripping from the Blue Shield’s protection.

What the international community will be able to do to stop Israel, however, is yet to be seen. “Any damage to cultural property, irrespective of the people it belongs to, is a damage to the cultural heritage of all humanity, because every people contributes to the world’s culture,” the 1954 Hague Convention’s text reads in its preamble. In theory, it is the first and the most comprehensive multilateral treaty dedicated exclusively to the protection of cultural heritage not only in times of peace, but also, and especially, during an armed conflict: where, in addition to the humanitarian toll, the large-scale destruction of cultural heritage risks to weaken the foundations of communities, lasting peace and prospects of reconciliation.