After Imm Aziz. On the disappeared sons of war and the eternal expectation of the mothers

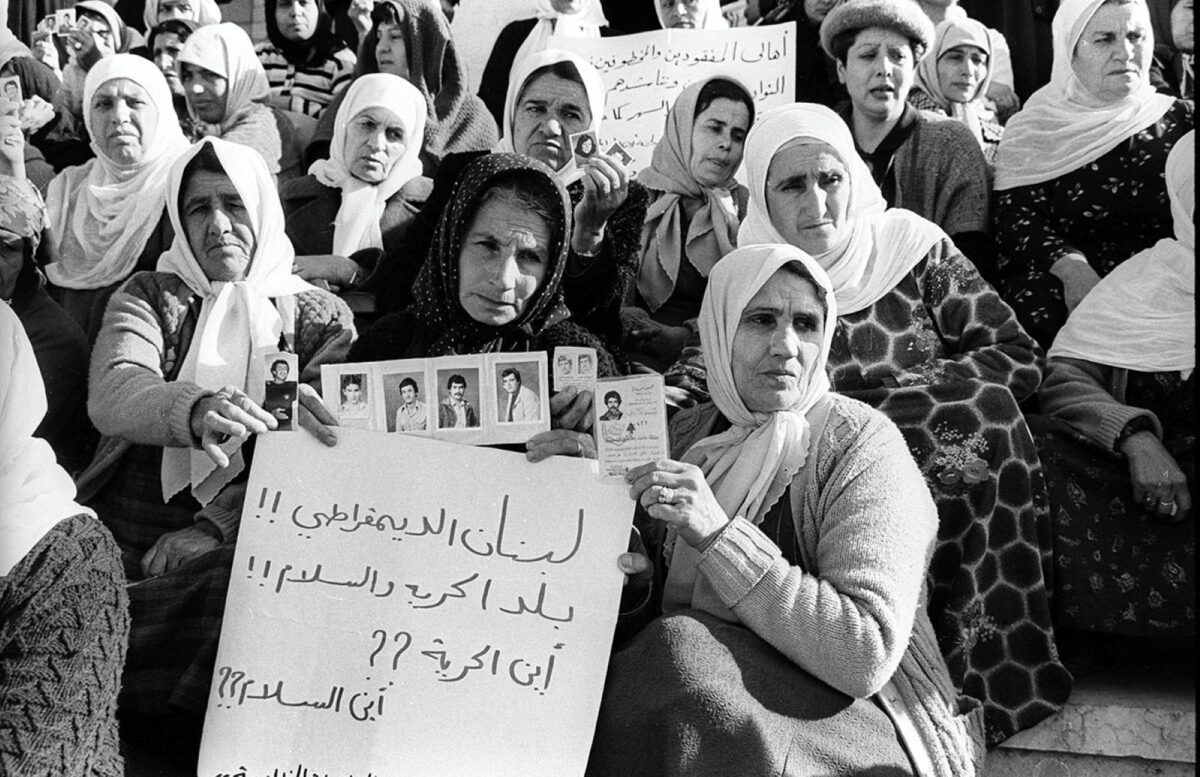

From April 13, 1975 to October 13, 1990, 5643 days have passed, counting leap years: 1976, 1980, 1984, 1988. And for each one, at least one massacre, the expansion of an occupation, the undercurrent of a war that seemed endless: Tell al-Zaatar; the occupying Israeli troops in the south and Syrian ones in the north; the withdrawal of the Multinational Force under the pressure of newly-formed Hezbollah; the last, fatal blows of the War of the Camps. In fifteen years, an average of 26 and a half people were killed every day – and three made to disappear: kidnapped, tortured, locked up in some underground prison, perhaps across the border, and if even killed, their bodies never returned to their families. From April 13 this year, every day, for fifteen years and six months, the fiftieth anniversary of some massacre, occupation, sub-chapter of a war that seemed endless will fall; every day the fiftieth commemoration of the death of 26 and a half people, and the forced disappearance of three.

In total, the disappeared persons of the Lebanese civil war are an estimated 17,000: and although fifty years have passed since its eruption – twenty-five since its end -, the dimension of expectation and pain of disappearances’ survivors would be more accurately measured, if it was possible, in thousandths of seconds. At least to give an idea of the incalculable greatness of the most counter-natural among the injustices: that of a mother who loses her child and dies before finding him again.

Celebrating the memory of Ghassan Kanafani in 2018, Palestinian novelist Ibrahim Nasrallah addressed the late author and activist in a Facebook post: “Do you know what the fate is, of the story that we do not write, of our unwritten story? Allow me Ghassan, to ask you from the heart, because I can scream and turn mad in front of you without feeling embarrassment. Because I am addressing you as one of us: Do you know the fate of the stories we do not write? They become the property of our enemies.”

By reflex, responding rhetorically and belatedly to this question, if we ask ourselves what has been the fate of the protagonists of Nasrallah’s Gaza Weddings – Randa, Lamis and Amna – the clear answer will be: they are still property of Palestine. Neither it fell into bloody Israeli hands the story of Kanafani’s Umm Sa‘d, another mother of martyrdom, another Palestinian, another refugee and freedom fighter in the camp of Burj el Barajneh: the over-populated two square kilometers where also Imm Aziz was from. Another story that, through its same narration, has escaped the clutches of the enemies.

Imm Aziz

Everyone in Burj el-Barajneh remembers Amina al-Dirawi as Imm Aziz, according to the Arab custom of taking the name of the first child introduced by the parenthood degree: which is imm, ‘mother’ in Arabic. But to Aziz, and to each of the other three young boys – Ibrahim, Mansour and Ahmad – Amina’s fate would have bound her far more deeply than to the simple mocking epithet of the laws of matronymic. As if fate could be foreseen in the name – of the mother with that of the first of the children – and this reversal was reflected in the survival: of the mother, this time, to each of the children. Imm Aziz remained orphaned by her boys until her last breath. She died in October 2022, at the age of 88, without having collected any information on the fate of the four kidnapped on a morning of September during the Lebanese Civil War: it was 1982, and in the Palestinian refugee camp of Burj el-Barajneh, south of Beirut, the Dirawi family was having a normal breakfast. The last time all six would be together. Not far from there, the massacre of Sabra and Shatila was taking place, deforming other mothers in the heartbreaking scream of the aftermath of the massacre.

“That was a black day,” repeated the widow’s voice in a documentary screened on Mother’s Day in a museum in Hamra, Dar al-Musawwir, a couple of years ago. “The day they were abducted, the day I was separated from them was a black day.” Since then they have remained that young: from the oldest, Aziz, 31 years old – to the youngest, Ahmad, just 13. The mirrored numbers of those who won’t grow up, nor will they see their parents whitewash, and who knows if they will ever find their way home.

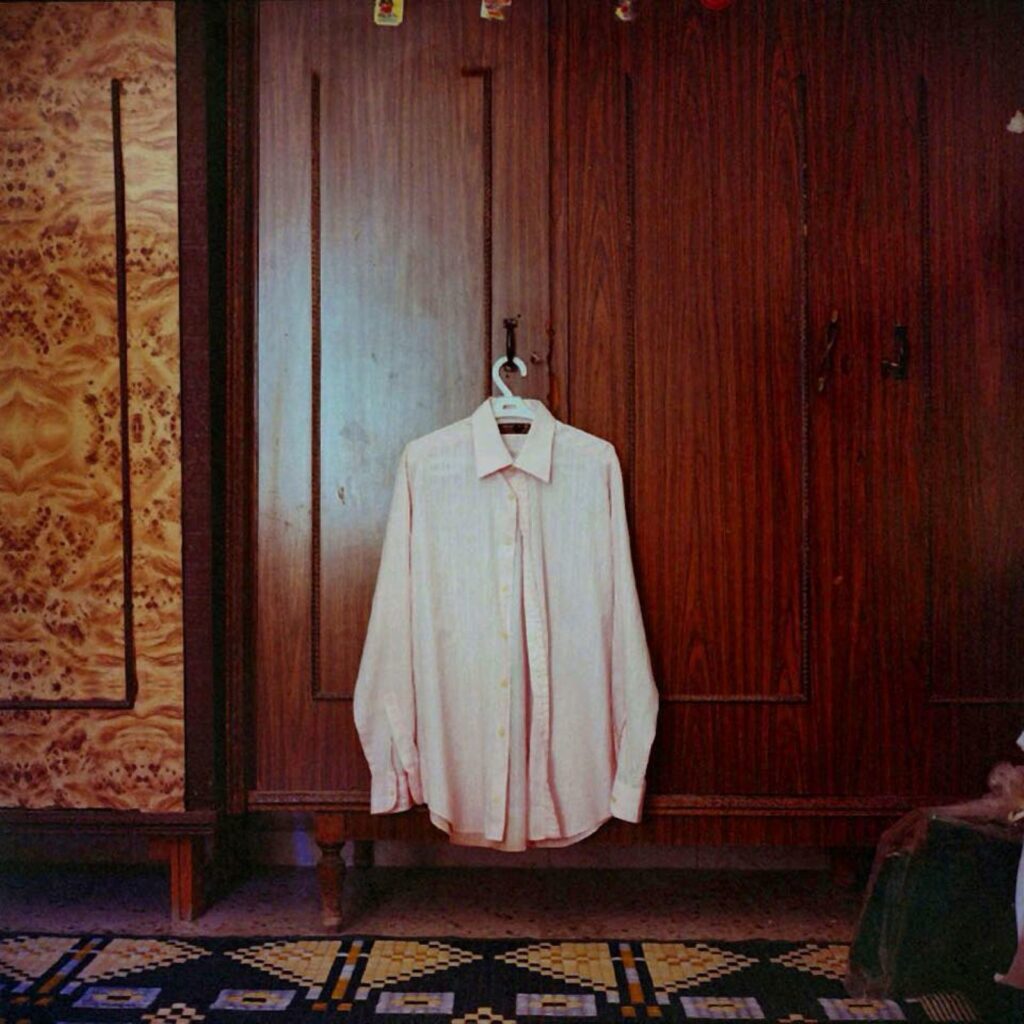

The disappeared children’s personal belongings that Imm Aziz has kept for forty years, waiting for their return. In the picture, Aziz’s pink shirt that his mother tried to hand him at the moment of his abduction. Source: The Missing of Lebanon

The disappeared children’s personal belongings that Imm Aziz has kept for forty years, waiting for their return. In the picture, Aziz’s pink shirt that his mother tried to hand him at the moment of his abduction. Source: The Missing of Lebanon

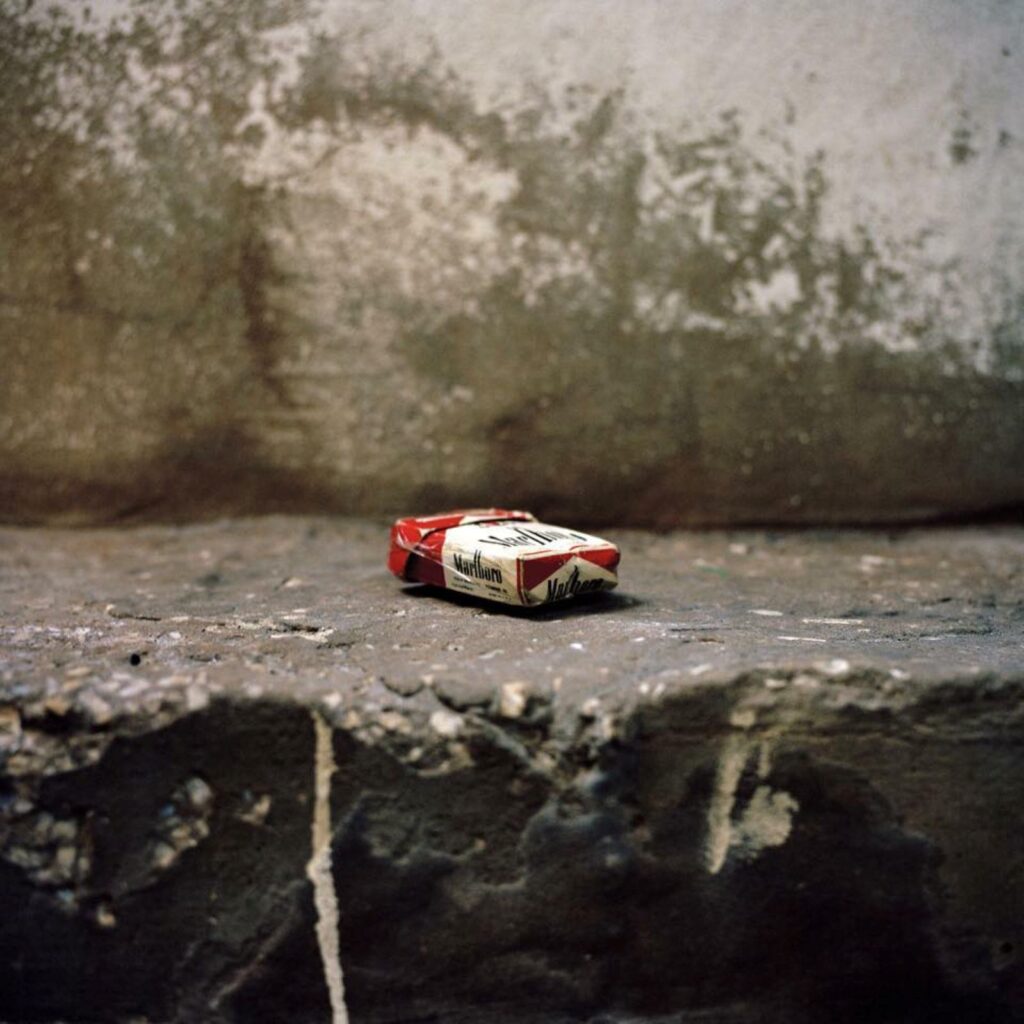

The disappeared children’s personal belongings that Imm Aziz has kept for forty years, waiting for their return. In the picture, Aziz’s newly-opened Malboro cigarettes, dating 1982. Source: The Missing of Lebanon

To avert their loss, Imm Aziz, the perennial mother, the lingering, the personified wait, had preserved a bunch of objects: so that when they return, they would be able to recognize each other. And in that eternal present had been waiting for forty years Ahmad’s school satchel, made of red leather with green borders; Aziz’s Malboro cigarettes – the package, just opened, with the date 1982: the year of the disappearance; and his pink shirt, which his mother tried to hand while they were taking him away on the truck, and chased him in vain, as if wearing a cloth that was certainly his favorite could somehow mitigate the abduction. The snapshots of Rome, Open City, and Anna Magnani’s race in via Montecuccoli behind the German van, that frenzied scream, then the fall, will sound rhetorical, but will give an idea – to anyone who remembers that famous scene – of what desperation means when someone you love is taken away from you. And of the unquestionable inhumane laws of war which certainly harm everyone: but innocent families, amputated families, somehow more in depth.

Italian actress Anna Magnani in the famous scene from Roberto Rossellini’s film Rome, Open City (1945).

“Some of them were taken by the Israeli army and others were held by the Lebanese Forces, and until today I don’t know in which hands they ended,” repeated the woman in the documentary, with a blank gaze and in her hands a photograph of herself – thirty or forty years ago – invoking justice for the four boys that time, going backwards, has made eternal children. “I lost my home and my country, but losing your children is different: no one forgets a child.” And just as Palestine, the land of the origins, has remained untouched by the symbols of its celebration – a map, a key, a flag and a kuffiya – constantly recalled, proudly affirmed, so those young men framed in the hanging photographs on the black mourning dress of seventeen thousand mothers will not perish: as never do ideals.

For forty years, Imm Aziz has kept the window above her bed open in case her children came back one day, walking down the alley behind the window in the camp of Burj el Barajneh: to make sure she saw them when they finally came home.

A photo of Imm Aziz’s four children, Aziz, Ibrahim, Mansour and Ahmad, on a table inside her room in the Palestinian refugee camp of Burj el Barajneh, in Beirut’s suburbs. Source: The Missing of Lebanon

The forcibly disappeared and the law

Although the civil society has continued to keep the issue of missing persons in public view, in fact, by pressing the Lebanese authorities to conduct a complete accounting process, the legacy of waiting is still kept in the maze of family voids. In 2014, the State Consultative Council, the highest administrative judicial authority in Lebanon, recognized the right to know in a high-profile decision: however, despite having signed the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (ICCPED) in 2007, it still has not ratified it.

However, outside the hostile and often sterile boundaries of the law, a new, unprecedented hope emerged last December, when social media platforms have been flooded with lists of names and photographs of Lebanese detainees who have been freed from Syrian prisons following the fall of the Assad regime. Users have shared audio clips and lists of names belonging to an alleged 700 Lebanese individuals missing since the times of Syria’s occupation, despite Syrian officials having repeatedly said there were no more Lebanese prisoners in their jails. Among them, Ali Hassan Al-Ali, identified by the inhabitants of his native village, Tasheh, in the northern region of Akkar: from where he had been missing for 39 years. Arrested at a checkpoint in the North in 1985 by the Syrian authorities for alleged membership with the Islamic Unity Party, since then disappeared, over the years his family made several enquiries about his fate – but never received a clear answer from the Syrian authorities. He was 18 at the time, he came back – out of the prison of Hama – an old, yet still recognizable, devastated man.

Obviously less hopeful is the expectation of the relatives of those who ended up in Israeli hands: and yet, even with the last hopes lost away, that expectation is the only thread left to snatch the lives of 17,000 people from oblivion: to keep the lives of as many mothers afloat. For in Lebanon’s lack of sufficient legislation in this regard, and of an official and comprehensive list of the disappeared, it is evident that the burden of such memorialization, the responsibility of not forgetting, ends up lying in the already devastated hands of the relatives who survived: and, among all, in those of mothers, who decades after the abduction of their children begin to disappear too – of deaths somehow regretted and disappointed – with the photographs of the boys still hanging on their chests, the dear objects on their knees, and the hoped illusion for a wait that will survive, hopefully, at least until tomorrow. That after Imm Aziz there will be someone willing to smooth Ahmad’s school satchel, and iron Aziz’s pink shirt, and prepare the beds for Ibrahim and Mansour, since after forty years away from home they must be very tired, and before answering to the gusts of what-happened, where-have-you-been, how-about -your-mother, for sure they would ask for sleeping.

Imm Aziz sits in her house under the photos of her four sons who were kidnapped in 1982. Source: The Missing of Lebanon