There’s a pattern we’ve perfected in Lebanon: a foreign diplomat says something blunt, people across the political spectrum get offended, we argue over tone, and somehow no one addresses the substance. That’s exactly what happened with U.S. envoy Tom Barrack’s now infamous warning, that Lebanon risks ceasing to exist as a functional state, and could “become part of Bilad al-Sham again” if it does not take decisive action to reclaim its sovereignty.

What should have triggered urgent institutional introspection instead provoked a national tantrum.

And yet, while some Hezbollah allies predictably rejected Barrack’s remarks as Zionist theater, and even anti-Hezbollah voices scrambled to frame them as external interference, something much more significant was happening quietly in the background: Barrack met with Hezbollah.

According to multiple reports, Barrack met in secret with MP Mohammad Raad, head of Hezbollah’s parliamentary bloc. The message is clear: the U.S. is willing to separate the weapons issue from the broader political gridlock and address it directly with Hezbollah, bypassing the Lebanese state if needed.

This is not just geopolitics. It’s a mirror. A reflection of what we’ve become: a country so weakened, so paralyzed, that foreign powers now engage its non-state actors as equal or greater players than its elected officials. It’s not a conspiracy. It’s cause and effect.

And we earned it.

Lebanon has failed to demonstrate even the most basic functions of sovereignty. Our judiciary is frozen. Our borders are porous. Our public institutions are decaying. A multinational terror cell was just arrested in Baabda, not the Bekaa, not some obscure border village, Baabda, minutes from the Presidential Palace. And we’re still acting like the insult lies in what Barrack said, rather than what that arrest confirms.

Sovereignty is not a flag or an oath, it’s an infrastructure of control. And we don’t have it.

Yes, President Aoun declared that anyone who has sworn to defend Lebanon twice — once as army commander, once as president — would never betray that oath. But oaths don’t patrol borders. Oaths don’t disarm militias. Oaths don’t ensure salaries, electricity, or clean water. They’re statements of intent, not indicators of capacity.

Meanwhile, Prime Minister Nawaf Salam, for all his legal intellect and diplomatic finesse, has not demonstrated a shift in priorities. We don’t need more ceremonial speeches or presence at festivals. We need a head of government who treats security as the national emergency it is.

The state should be convening emergency strategy sessions, not clinging to symbolic posturing while foreign actors engineer the real conversations behind closed doors.

This isn’t to romanticize U.S. involvement. Nor is it to suggest that Barrack’s tone wasn’t strategic, even provocative. But the discomfort his words caused has more to do with their accuracy than their arrogance.

Lebanon is at an inflection point, and the international community sees it. The government’s formal response to Barrack’s roadmap — a seven-page proposal outlining a potential path to disarmament in exchange for Israeli withdrawal — was well received. Barrack called it “spectacular”. That’s rare praise from a U.S. envoy. It means someone, somewhere in our system, is still trying.

But diplomacy isn’t enough.

You cannot claim to be sovereign while another armed actor controls foreign policy, while terror networks fester in your capital, while your public services operate on life support, and while your economy is held together by remittances and aid.

You cannot expect the world to treat you like a state when you behave like a hostage.

And you cannot lecture the world on pride while ignoring that in 2025, your country still runs on generators, your minimum wage can’t cover a week’s groceries, and the only consistent government service is denial.

If all of this doesn’t provoke outrage, but a foreign envoy’s warning does, then yes, you are part of the problem.

Let’s stop pretending that this is about tone, or Western interference, or the sacredness of sovereignty. What’s at stake is far more fundamental: either we act like a state, or we lose the privileges of being treated like one.

It’s time to stop getting offended by the diagnosis and start confronting the disease.

Pass the diaspora voting reform. Deploy the army to secure the border. Launch judicial accountability. Put internal security and arms regulation on the national agenda. Demand more from the prime minister than presence. Ask the president to stop reciting oaths and start enforcing authority.

Because no one is coming to save us.

Barrack didn’t threaten us, he reminded us of what history already knows.

If we don’t get our act together, the region — and the world — will move on.

And Lebanon will become exactly what we fear: not a final state, but a forgotten one.

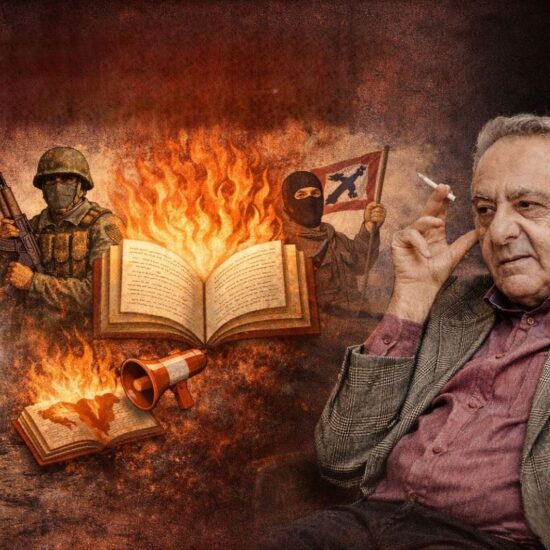

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a Political Psychologist and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution at the Lebanese American University.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW