Residents of border village of Aitaroun walk back to a destroyed, liberated land

Aitaroun, south Lebanon. 125 kilometers from Beirut, and only three from the settlement of Avivim, the first in northern Israel – so close to what today is known as an impassable border, that in the Ottoman Empire of 1596, the village was named under the district of Safed, the highest city in the Palestinian Galilee.

On the other side of a moving line, shifted by the weight of events and the tenacity of inhabitants – where the rules of engagement no longer apply, but the stone thrown, the bullet dodged, the first step over the barricade, the weeping over the martyrs’ body – in what here will always be called ‘occupied Palestine’, Saliha – the original name of the moshav of Avivim – was placed by the 1920 Franco-British boundary agreement within the French Mandate of Lebanon border, thus classified as part of Lebanese territory: it was one of the 24 villages later transferred from the French Mandate of Lebanon to British control in 1924, in accordance with the 1923 demarcation of the border between the Mandatory Palestine and the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon.

Different borders, for different times; places, both, whose fate depended on the shifting of a line: imaginary, in the case of a national border – but very real, in that of a barricade erected by the occupying forces. What the Ottomans associated with the district of a Palestinian town, and the French would later undoubtedly call Lebanon – those mobile, non-existent barriers, drawn on a map capable of prescribing the real – and always translated into armies, barbed wire, walls, forced displacements – today undergo the drawing of other limits, of new prohibitions. But unlike then, a tangible line, in the form of rows of Israeli soldiers armed from head to toe, and concrete walls on the road that once led to the village – linking Bint Jbeil to Aitaroun – contradicted the time limit of a supposedly temporary occupation, establishing a new reality on the ground. The deadline has passed, the occupants are staying.

“You see, that is Palestine. Those, instead, are the Israelis,” says Ali, a 28-year resident of south Lebanon, in the first moments after entering the liberated village last Sunday, February 2, pointing at the virtual Blue Line, and the colonial constructions of the very first Israeli settlements: Avivim, Yir’on, Malkia – once, respectively, the Palestinian lands of Saliha, Qadas, and Al-Malkiyya. The difference between a free land and a liberated one is defined by the heaviness of the step in the latter, the constant reminder of death, destruction, and loss: only a few handfuls of kilometres away.

The line, in this case, has been shifted: and the land liberated, by walking, pushing, defying the fear of bullets, drones and grenades, the women wearing, over the long black cloth, the photographs of their loved ones killed, to be searched for, exhumed, so they could finally clean them up, finally make them rest.

“We walked in silence,” recalls Ali a few days later, refuting the expectation of my question about celebrations, gunfire, songs of joy or cries of despair. Only an old woman, having reached the place she used to call ‘home’ and everyone now refers to as ‘demolition site’, crying, screaming, searching for her martyred children, lifts, hoping to find their bodies, all the stones: even the smallest pebbles.

An image of despair, all the more evident as it stands out against a landscape of composure: everyone else, a silent procession. Aimed at one purpose: returning to exhume the dead, then burying them with dignity. “There was nothing to go and discover, we knew what to expect,” comments Ali. The residents of Lebanon’s southern border villages have been displaced since the beginning of the war in October 2023, and for eleven months, until the temporary ceasefire came into effect on November 27, they were barred from returning – along with the right to know if their homes were still standing. Having returned en masse, on the first day of the truce that was set last 60 days, until the complete withdrawal of the Israeli troops, to realise that the houses were still standing, that the village still existed, they were evacuated, once again, to watch in disbelief the impotence of the Lebanese army, under whose deployment the Israeli forces occupied more land than they had managed during the eleven months of war. In the two months of the so-called ceasefire, which in fact turned out to be a reinforced occupation, more territory was razed, burnt, vandalised, than was bombed.

The kitchen of one of the houses that once inhabited Aitaroun – houses also inhabit villages, as well as being inhabited – seems to have been melted down: Hassan, the owner, had returned on 27 November, finding it intact. Two months later, it is impossible to recognise its original structure – or even imagine it, for someone like Ali who entered it for the first time last Sunday. Of the structures still standing, however, where some of the furnishings have been spared, it is almost more hateful to recognise the human passage, the smell, the horror that Israeli soldiers have abused them: sleeping in those beds, eating on those tables, washing in those toilets – then splitting in half the same beds, the same tables, and the toilet bowls.

The remains of what was once Hassan’s kitchen, melted by the devastation left behind by occupying Israeli troops during the two months of the so-called ceasefire. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe

Just as if the land was personalized, and objectified the brutality of the Israeli soldiers – men, women, “younger than me,” Ali comments, “and yet thirsty for destruction, unlike us,” he continues – also the house turns into a living being for whose rape one despairs. And the soldiers of the Israeli occupation – not defense – forces, the IOF, result in dehumanization. Even as you see them, in the flesh, aiming their M16s at rows of unarmed civilians. And laughing, laughing at the traces of their own vandalism. Similarly, “this is my house,” says a woman in her thirties searching for the remnants of what was once her world – and that she’s determined to rebuild – “while this,” with contempt, “is the passage of them.”

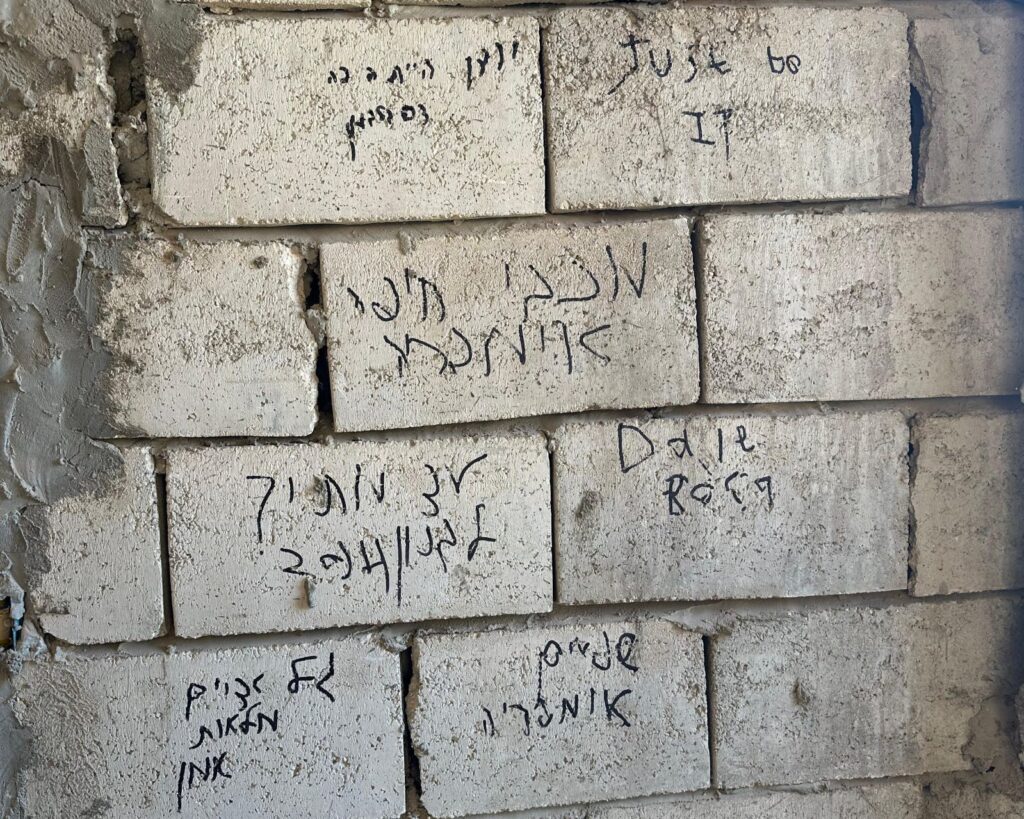

Hebrew writing on the walls recites the verses of Kasser w Karreb, literally ‘Break and Destroy’, a recent Israeli song, with the name of the occupation battalion specified. Break-and-destroy: to make any attempt to live impossible.

The living room of a house still standing, in which the traces of the occupying soldiers’ passage are clearly visible. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe

The ugliness of Aitaroun’s destruction, compared to that of other villages completely razed to the ground, such as Aita al-Shaab, is that in Aitaroun, some buildings were left standing: to witness the vandalism of the occupation, to force the residents to demolish, like a terminally ill person whose suffering one wants, must end.

At the same time, it is also thanks to that encounter that you stop being afraid of those such young enemies: observing the traces of their human activities, drinking, eating, going to the bathroom, reminding yourself – without normalising – that ethnic cleansings and genocides are carried out by people. That it is people that you can fight: not drones, not bombs.

Ali, who found himself displaced in the Beirut neighbourhood of Ein el-Rommaneh, not far from Dahiyeh, admits that during the two months of intense shelling he used to fear Israel, “but not anymore,” and he continues: “after seeing them in person, it is impossible to mythologise them. Hearing about Israelis without ever meeting them would make you terrified, because we all know what they’ve been capable of doing in Gaza. But once you reach a place like Aitaroun, and you see they’re still there, looking at you, with their shaved, human faces, you suddenly realise they are not scary. You can approach them, walk the road that belongs to you, and push them away.”

From the ground of the liberated village, Ali collected tuna cans, bags of chips, snacks, leaflets written in Hebrew, hundreds of bullets, water bottles, rubbish, to prove to himself, to his friends, to the future, that the liberation happened – and it was the civilians who led it.

Rubbish left by Israeli soldiers in a house during the occupation of Aitaroun. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe

Acts of vandalism written in Hebrew left by Israeli soldiers during the occupation of Aitaroun. It reads: ‘May Israel destroy the Arabs of Lebanon’. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe

Acts of vandalism written in Hebrew left by Israeli soldiers during the occupation of Aitaroun. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe

A people-led liberation

Ali was the first person entering the road that the Israelis had been barricaded for weeks. “I am not from Aitaroun, but I wanted to witness what was happening, so I took a video of that historical moment.” With his back to the entrance of the destroyed village, he observed the displaced residents’ first entry in fifteen months of forced exile: walking backwards, letting the anaesthetisation to the destruction of the inhabitants – men, women, children and the elderly – unfold on their faces without reaction.

“There was almost no reaction,” he repeats, “they knew what they were going to encounter. Only in Aitaroun,Israel killed 122 people. No one will ever know which one is whom, which leg belongs to whom.” Walking in an ordered silence, everyone looks for their house, then stands in front of the mountain of rubble it became, finally starts moving stones and looks for body parts. They won’t be even able to guarantee a funeral for a full corpse: never as much as in the past year and a half, Israel declared it has the right to maim.

And as we speak, the villages of Kfarkila, Blida, Houla, Markaba, Yaroun, Odeisseh, are still occupied. Signs erected behind barbed wires are reading ‘Closed military area. No entry’ – and in front of it, a group of women kept on chanting “Israel out,” until they could break the barrier: in Aitaroun, for six days they have been standing in front of a line of Lebanese soldiers and behind another dirt barricade, while Israeli troops remained stationed in their village.

A sign erected behind a barbed wire by the Israeli forces prohibiting residents to go back to their villages. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe

It seems, indeed, the application of the West Bank paradigm, with roads blocked, protracted and illegal presence on the ground, changing rules of engagement, abductions of unarmed civilians, explosions and demolitions, houses set on fire, a machine of terror operated through grenades, tear gases, explosives, landmines, and assault rifles. Only on Sunday, January 26 – when the 60-day deadline for the withdrawal of Israeli occupation forces from Lebanese territories, as stipulated in the ceasefire agreement, was supposed to officially expire, and southern residents mobilised in a mass march to their towns and villages, determined to force the occupation forces to retreat, despite the Israelis refusing to withdraw – five people were killed while attempting to enter Aitaroun. In the ensuing violence, that same day, as citizen footage captured moments of direct confrontation with Israeli soldiers and Merkava tanks, the Israeli gunfire killed 24 civilians and injured 124 others, including 9 children and a Lebanese army personnel. An interactive map produced by the multidisciplinary research center Public Works Studio can help tracking Israel’s daily attacks on Lebanon, including the types of bombardment, the nature of the targets, and the number of civilian casualties: since the truce agreement took effect on November 27, and the Lebanese army started its deployment in the south, Lebanon has recorded at least 823 Israeli ceasefire violations.

“While the Israelis were pointing their rifles at us, and one of our soldiers was helping two orphans erect a poster with the photograph of their loved one whose body they wanted to be able to exhume, the enemies fired live ammunition at us. It was a deafening roar. Meanwhile, a drone kept buzzing above our heads,” Ali recalls. A little boy who was there with the young woman who must have been his mother – also wearing the photograph of her missing husband on his chest – took the soldier by the arm, and asked him ‘why are you looking at me, shoot at them, instead!’ and the soldier, whispering, as if he was afraid the Israeli troops might hear him, replied cautiously: ‘if this were my weapon I would, but I can’t’. “Our soldiers have orders to obey,” Ali comments, “we understand this, and it is unfair that some of them were killed for nothing, for standing there pretending to guard us, the people. But their presence, for us, is useless.”

“Standing behind women and children screaming curse words at the Israelis, and begging the Lebanese soldiers to let them enter, eventually they waited for us to open the road. Imagine: a military troop, not that properly equipped if compared to the Israelis, yet the only ones able to protect us with weapons, slowly proceeding with their American-produced tanks behind us, while, amidst destruction, signs like this emerged,” and he shows me the picture of a blue-background poster erected above a pile of rubble, with the inscription, in Arabic: ‘America mother of terrorism’.

A view of Aitaroun razed to the ground by the Israeli occupation forces. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe

In this way, thinking of the real line of Israeli barricades as imaginary, and not being afraid of it, pushing it – and believing in the long imagined line of liberation as to make it real, Aitaroun was liberated from Israeli occupation.

In the silent procession, Ali in the lead, walking backwards and filming, then the photographs of the martyrs preceding the orphans and widows, the men, finally the elderly, a few journalists, and the Lebanese army vehicles, a woman looking for her husband’s remnants, found, next to the site of what used to be their house, the shoes he used to wear – only one boot -, his jacket, and a hand that must have belonged to his dismembered body. Other returnees helped her to get the rest of the corpse out of the rubble, but could not find any part of it. So she took the picture of him from her chest and placed it on the rubble where he must have been, then placed his lonely boot on the prayer rug, as if he was taken back. From there, she will begin again.

The boot of a martyr filled with white roses and placed on the prayer rug during the noon prayer in Aitaroun. Photo credits: Ali Wehbe