One year after the death of the famous Lebanese writer, Beirut, his hometown, comes together in commemoration with events and exhibitions. However, something about Elias Khoury, that had long since ceased to belong to the man and begun to belong to literature, had already been travelling among readers around the world - now clinging to what remains of his genius: his everlasting books

I went to Saint John the Baptist cemetery. I searched among the scattered graves beneath the cypress trees. I read all the names, and on a semi-abandoned grave, whose black titles had already become dust-colored, no flowers on it, I saw the name of Elias. I went closer and read the name next to it, Michel Iskandar. It must have been someone else – so hidden in the most remote corner of the Orthodox cross-shaped cemetery -, but the plaque engraved on the white marble resembled Elias and his brother as young men. I went closer to him, or to whom I thought it was Elias Khoury, and I read his brother’s name, and I read Milia’s name, and Mansour, and the names of Yunes, Khalil, Nahila and Shams, I read Little Gandhi, Adam, Yalo, and a number of anonymous White Masks around them. They were all there, there was no set of letters that I hadn’t read before, it was like a long dream from which I couldn’t wake up.

“Let me begin with the fall of the city, because stories begin with falls,” he taught us in My Name is Adam (2012), the first volume of the Children of the Ghetto’s trilogy: and as a narrator, a reader, and a mourner, I will begin the story of Elias Khoury with his fall. It feels as I am stealing from his genius, listening to the rustles and whispers of voices that I have repeatedly marked in his well-thumbed books, “and I discover that all stories are like this or, to put it more precisely, that this is how stories are born – in fits and starts, whispered, near silent…”

The grave where Elias Khoury is buried with his brother Michel Iskandar at the Saint John the Baptist Orthodox cemetery in Beirut. Credits: Valeria Rando

Elias Khoury died last year, on September 15, at 76 years old. One of his characters, Little Ghandi – his dead body found in a trash heap in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War – also died on September 15. “Beirut was different that morning,” he wrote in The Journey of Little Gandhi (1989). “Morning carried the smell of death. There were armed men everywhere, and commotion, as if those who had died never died, as if the war hadn’t ended, as if it had just begun.” In the voice of one of the novel’s protagonists, you can almost hear an echo of fear: am I the murder of my characters, or am I only their narrator? The narrator and the narrated, the murderer or the creator, in the literary universe of a man who recounted the lives of the marginalized elevating them to the everlasting status of literature, it makes no difference. But Gandhi was little, marginalized and abandoned: while Elias, in turning the small, exiles, and abandoned into literary characters, departed as a giant.

Yet, despite having left behind an immense cultural heritage – literary, theatrical and editorial –, his grave has nothing of the monumentality that usually accompanies great writers. It is a small black square, embossed with a white Orthodox cross, on the top row of the third column of what must be the tombs of the ordinary people. Of the common, marginalized men. Born in Achrafieh, when Achrafieh was a forest and was called الجبل الصغير, Little Mountain (1977) – buried in an Orthodox cemetery next to a Palestinian refugee camp. A little closer to Palestine, to which he learned, not without suffering, to belong.

And without mythicizing it, without pity. The deep, visionary power of Elias Khoury, laid also in re-humanizing Palestine to the point of making it as worth telling as any other story: a story of love, of fighting, of childhood, illness, dreaming, of regret. Also, a story of mistakes.

As he wrote in what maybe stands as his masterpiece, Gate of the Sun (1998): “I was about to cut an orange from the branch so that I could taste Palestine, but Umm Hassan yelled, ‘No! It’s not for eating, it’s Palestine.’ I was ashamed of myself and hung the branch on the wall of the living room in my house, and when you came to visit me and saw the moldy branch, you yelled, ‘What’s that smell?’ And I told you the story and watched you explode in anger.

‘You should have eaten the oranges,’ you told me.

‘But Umm Hassan stopped me and said they were from the homeland.’

‘Umm Hassan’s senile,’ you answered. ‘You should have eaten the oranges, because the homeland is something we have to consume, not let consume us. We have to devour the oranges of Palestine and we have to devour Palestine and the Galilee’.”

What stands out the most, in this as in many other of his novels, is Khoury’s dedication to preserving the memories he collected during his visits to Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon – his effort to keep these stories alive in the minds of his readers: and not too different from his great predecessor and mentor, Ghassan Kanafani – yet with a more dreamlike tone: but universal, and with the ability to bring together, throughout the novel and in the time of the novel, both the senile and superstitious voices – reverent towards an orange branch from Yafa, like Umm Hassan’s – and the irreverent, destructive, somehow desecrating ones that debunk myths and idols, like that of the young Yunes.

For literature is truer than reality: and if “we, writers, are condemned to oblivion,” he was recorded saying in an interview projected during the first commemoration of his passing, on September 15, 2025, at the Lebanese National Library, “then the truth endures in the literary work itself.” And the characters survive their creator who, maybe exaggerating his own power, feared of having become their murderer.

And the writer will be forgotten and there will be no flowers on his grave, which will continue to fade; and in a year’s time we will commemorate the anniversary of someone else’s death, and the books displayed on the shelves of the National Library will bear other names: but Gate of the Sun, in the meantime, has exited the door of the novel and taken root in reality – transforming, from name, into place. In 2013, a group of about 250 young Palestinian men and women in the West Bank, in sign of protest, erected 25 tents on private Palestinian land in the E1 area, northeast of Jerusalem, where Israel had decided to build more than 3,500 housing units. They called the encampment Bab Al Shams: after the novel’s title, Gate of the Sun.

“Bab Al Shams is the gate to our freedom and steadfastness. Bab Al Shams is our gate to Jerusalem. Bab Al Shams is the gate to our return,” read a statement from the Popular Struggle Coordination Committee at the time.

And still the voices of Yunes, Khalil and Umm Hassan, seem to echo: “It came to me then that you were right, but the oranges were going bad. You went to the wall and pulled off the branch, and I took it from your hand and stood there confused, not knowing what to do with the decayed offering.

‘What are you going to do with it?’ you asked.

‘Bury it.’

‘Why bury it?’

‘I’m not going to throw it away. because it’s from the homeland.’

You took the branch out of my hand and threw it in the trash.

‘Outrageous!’ you said. ‘What are these old women’s superstitions? Before hanging a scrap of the homeland up on the wall, it’d be better to knock the wall down and leave. We have to eat every last orange in the world and not be afraid, because the homeland isn’t oranges. The homeland is us’.”

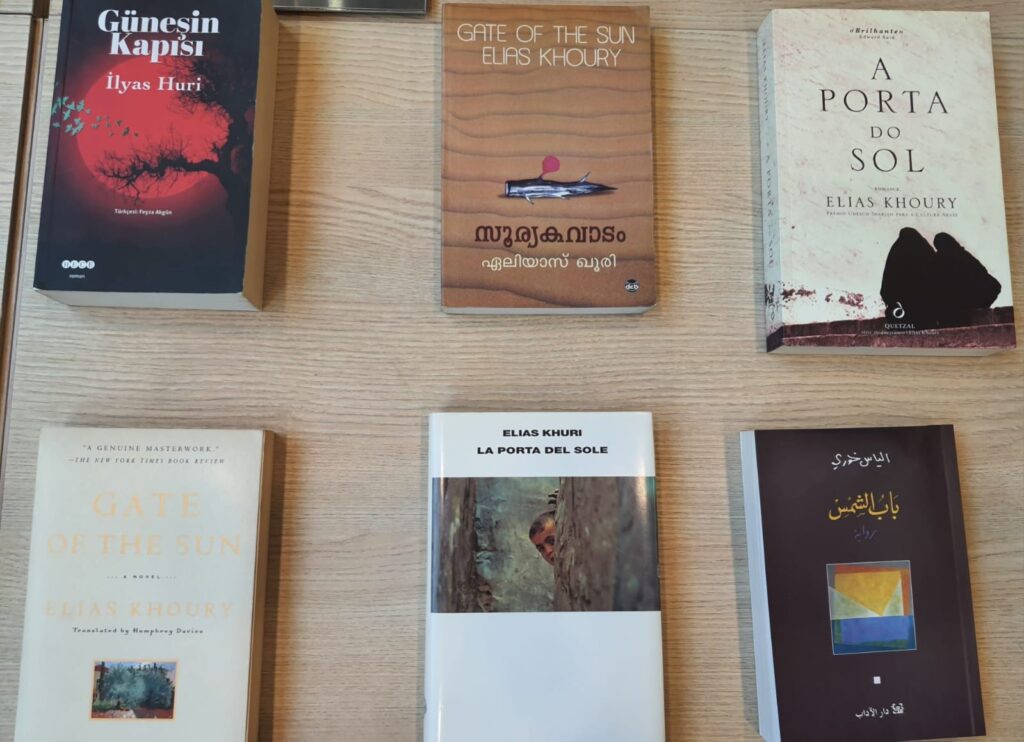

Exhibition of the various editions of Gate of the Sun during the first commemoration of Elias Khoury’s passing at the Lebanese National Library on September 15, 2025. Credits: Valeria Rando

Screenshot from Yousry Nasrallah’s film Gate of the Sun (2003), adapted from Elias Khoury’s masterpiece. Source: ALFILM Festival

On shadows, mirrors, and the purpose of writing

Elias Khoury once stated that if literature is a book, a writer’s ambition is only to add a page on it. And if not a page, a line. And if not a line, a word. That is the purpose of writing – to defend oneself and to resist death. From one of the most poignant pages of Yalo (2002): “grasping the secret of the squid, which Arabs called the habbar, or inkmaker. He understood that this sea creature was the first to discover writing, because it wrote with its ink in self-defense and to resist death. Its enemies were completely misled by the ink in their faces, and the cuttlefish vanished from their sight in the dense black thicket that the ink painted within the seawater.”

Now that the ink on their faces has become reality – and through Yalo and his visions of clay Elias Khoury has become immortal – what passed away one year ago does not seem so difficult to accept. Something greater than man remains – which in his old age he himself defined as a mere residue. “Every time a friend dies, a part of you dies with him,” he once admitted to his interviewer. “At the end of your life, three quarters of you have already gone. Literature is therefore the best place where the dead and the living can converse.” Divided in life by the departure of the loved ones, the man multiplies in literature because he has become all his characters and all his readers.

“When man nears death, he becomes brittle, like pottery baked over the fire of life that has lost its water,” reads one of the opening pages of Children of the Ghetto’s second volume, Star of the Sea (2018). And as an internal response coming from his literary corpus – his body of words – an echo: The Kingdom of Strangers (1993).

‘Stories don’t end,’ I said to her.

‘What does end?’ she asked.

‘The storyteller ends,’ I answered.

‘You are the storyteller,’ she said.

‘No. I am the story.’

“My story, though – and herein lies the paradox – needs those of others, if it is to take shape in words, and the others whom I seek have died, or disappeared and been transformed into parts of me,” reads another page of My name is Adam. “I sense them, and I sense that my body has become too cramped for us all and that I can no longer bear the sound of their voices.”

I summon their images before me and listen: it truly looks like a conversation between the living – us – and the dead – Elias and his lost world. Death and life are not present: indeed, the archipelago of his characters rises up in the middle: an arch which makes communication possible.

And if the living Elias Khoury was a Lebanese citizen, an Orthodox Christian, a writer, a fighter, a husband and a father, the one immortalized in his novels is a seven-year-old girl, a woman who does not unfasten her bra even to sleep because she remembers her grandmother’s sagging breasts. It is those sagging breasts and the bare feet of little Milia running through the alleys of an invisible city that happens to be called Beirut – and then suddenly stops in a vision, As though she were sleeping (2007). But it is also the hesitation before a wedding, the taxi ride to Chtoura, the severity of a mother who orders you to laugh while everyone else is crying with emotion: and the horrendous displeasure of a stranger’s mucus on the white cloth handkerchief inherited from the family, with which you were denied the right to wipe your tears away.

Poster for the multimedia installation realized by the Ayloul Festival in memory of Elias Khoury, ‘As Though He Were Sleeping’, hosted at Zico House until September 30, 2025. Credits: Valeria Rando

The only way Elias Khoury could have been capable of such sensitivity – even feminine – was by entering the dreams of his characters, as though he were sleeping. Reads the dedication of the book that inspired the multimedia installation realized, at Zico House, in memory of the late writer by the Ayloul Festival: “Death’s a long sleep from which one wakes not / And sleep’s a short death from which one must rise.” As if stirred by his absence, characters from his books seem to return to life – speaking, moving and unfolding within the walls of an old three-store building.

And the voices are overlaid with visual installations, dreamlike sculptures, a play of doors, shadows and mirrors that you happen to pass through, finding yourself – the spectator – reflected on the wall. Just as everyone has found themselves reflected in his books and begun to belong to them. Literature, too, is a world of shadows: yet more real than reality itself. And if only the dead can have access to the visions of the living – sleepers, dreamers – now that Elias Khoury belongs to the other world, he can certainly admire and write about ours. Yet those stories will not reach us.

In As though she were sleeping, Milia tries to explain to Mansour the difference between stories that have ended and stories that have died. “All families have at least one buried story that no one dares to unearth,” she says. But there are others – those that were never written: and this is perhaps the most difficult aspect to accept. That we will never know about the characters and lives that disappeared with him; that were unable to defeat death; that the squid did not release them into the sea, but has kept, jealous, within its ink sac.

Picture from the multimedia installation realized by the Ayloul Festival in memory of Elias Khoury, ‘As Though He Were Sleeping’, hosted at Zico House until September 30, 2025. Credits: Valeria Rando

Picture from the multimedia installation realized by the Ayloul Festival in memory of Elias Khoury, ‘As Though He Were Sleeping’, hosted at Zico House until September 30, 2025. Credits: Valeria Rando

- Although the exact date of Little Gandhi’s death is not specified, a reference in the book to the assassination of President-elect Bachir Gemayel on September 14, 1982 allows us to calculate the exact day. “The day before,” reads the English translation of the novel, referring to the day before Little Gandhi’s death, “when he heard the news of the explosions and the death of the president of the republic, this very laugh came back to him. He left his laugh in front of Spiro with the hat’s store and ran home.” (The Journey of Little Gandhi, p. 10)