The American University of Beirut’s Spring festival, known as AUB Outdoors, has long been a beloved tradition. Held over two days at the end of the academic year, it features games, food, and live music, all organized by a student-led committee to raise funds for the university’s financial aid program. For my generation and those before and after, this event offered a light and wholesome opportunity to visit campus—especially during the tumultuous years of the 1980s—and gave both children and university students a space to enjoy themselves.

Over time, however, the festival evolved. What was once a casual and accessible event has gradually become commercialized. Tickets are now prohibitively expensive, often requiring personal connections to obtain, stripping the event of some of its original spirit.

This year’s edition, held last weekend, featured the Palestinian rapper Marwan Abdelhamid, known as Saint Levant. Born to a Palestinian-Serbian father and a Palestinian-French mother, Abdelhamid represents a generation of young artists with multicultural roots and a strong social media presence. I hadn’t heard of him before—perhaps because rap isn’t my genre—but for many younger fans, this “saint” speaks for their generation.

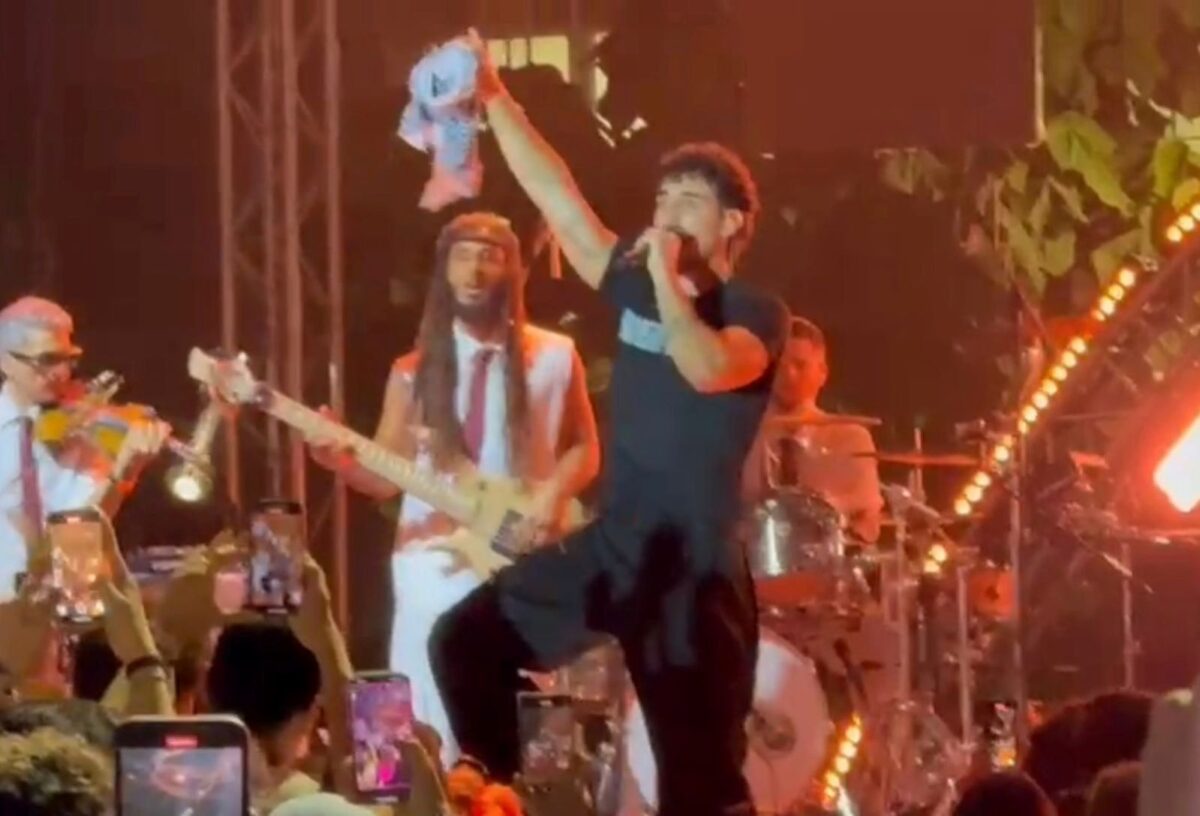

Naturally, Abdelhamid took to the stage to perform, but he soon shifted gears, transforming into a peddler of pan-Arab nationalism and an opponent of what he called “the global tyrant”—the United States. In widely circulated clips on social media, he is seen addressing the audience in a mix of English and Arabic, lamenting how he was deprived of learning “our history” during his time at the American International School in Gaza and later in Amman—mentioning Palestine, Lebanon, and Syria in particular.

He claimed that many in the audience had undergone the same educational experience, in which the ultimate goal was “to go to America.” He then went on to declare: “We Arabs, we are the Levant, we are the future of humanity,” adding that migrating to the West was simply “not nice.”

Later in the performance, he returned to the stage waving the Palestinian keffiyeh, paying tribute to the martyrs of Gaza, Syria, Algeria, Sudan, and Yemen—though conveniently forgetting others, whether due to selective memory or selective politics.

Here, hypocrisy becomes especially stark. While condemning the Western education system, Abdelhamid is a direct product of it—and one of its beneficiaries. His parents chose to send him to an American school, a prestigious private school that teaches the American curriculum and charges steep fees. That decision reflects a clear belief: that salvation lies in Western-style education. He would later attend the University of California, Santa Barbara, bypassing Arab universities altogether—including AUB itself, which now offered him a stage for this double-edged message.

So the question must be asked: did he come to discourage emigration, or to market a romanticized, populist narrative that boosts his fan base? Was the keffiyeh a symbol of true solidarity—or merely a performative prop pulled out when convenient?

At 24, Saint Levant is undoubtedly a success story for many of his fans. But it’s worth interrogating his words, rather than applauding out of Pavlovian reflex.

Perhaps Marwan should ask himself a few things: why did his parents enroll him at ACS instead of Kamal Adwan School in Gaza? Why didn’t he choose to study at AUB, the very institution that offered him both stage and spotlight? Has the Palestinian cause become a convenient brand to perform on stage—only to be zipped away into a designer bag once the gig ends?

These are valid questions that deserve honest answers, especially since this self-declared Palestinian revolutionary was reportedly paid an exorbitant fee for his performance—a performance that promoted a diluted version of Arab nationalism. He did not, it must be noted, donate his fee to support Palestinian students at AUB.

So, dear bro, dear juvenile saint: A hundred thousand and forty roses to those who believe in humanity and in true peace—the kind that safeguards dignity more than sweet words and catchy beats that stir the senses while dancing atop the blood of martyrs.

This article originally appeared in Nida al-Watan

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah