August 12 marked the 49th anniversary of the massacre of Tel el-Zaatar, which followed almost two months of siege during which 3,000 Palestinians and Lebanese were killed by Phalangist militias. This article, analysing lost and rediscovered documents, is an attempt to prevent that massacre from being forgotten - for oblivion deserves to preserve many stories, but not that of Tel el-Zaatar

I went looking for Tel el-Zaatar: I couldn’t find it. The concrete esplanade of what was supposed to serve as a military airport based in Dekwaneh – and the new inhabitants use for jogging – has flattened the hill that once stood there, and the forced urbanization that followed the destruction of the camp after the massacre has eradicated the thyme bushes. Tel el-Zaatar, hill of thyme. Of the passers-by distracted by preparations for the celebrations of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary – all too young to remember – some are too young and too distracted even to know.

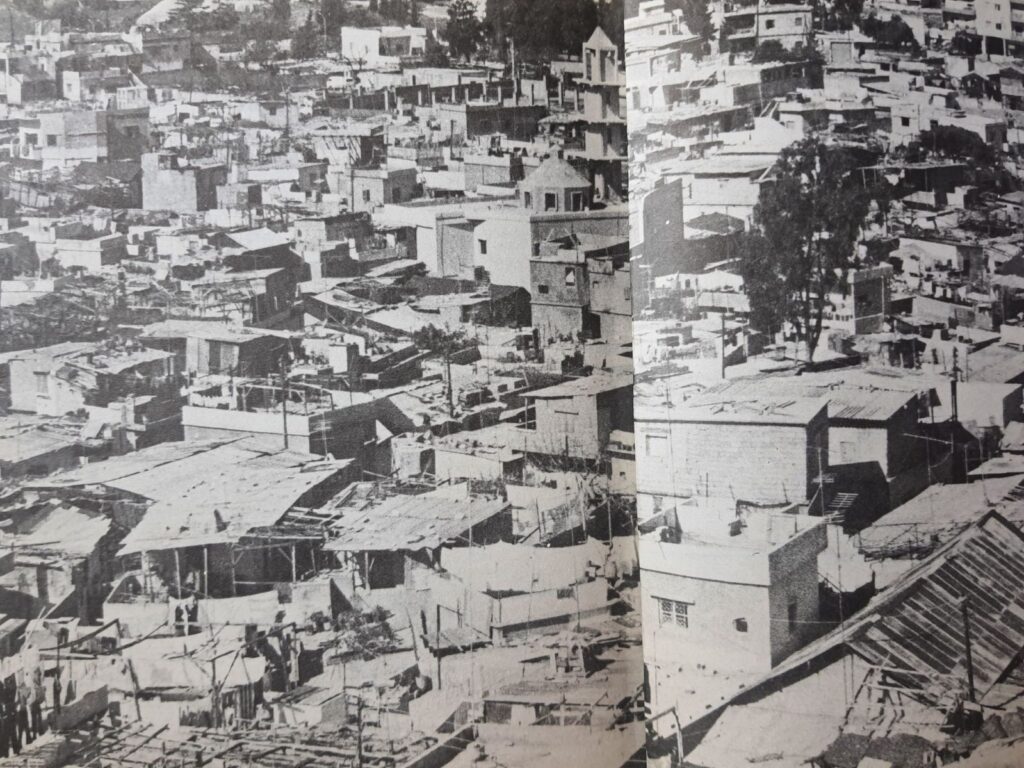

To know that Tel el-Zaatar was once home to one of the most densely populated Palestinian camps on the outskirts of Beirut – along with Nabaa, Dbayeh, Jisr el-Basha, and the shantytowns of Karantina and Maslakh – and that not a single stone remains, nor the ruins of a house, nor a plaque or a monument to commemorate. Not even the empty space that in the overcrowded only square kilometer of Shatila, paradoxically, prevents from forgetting, and rules: no building allowed here, and every September 16 brings together the survivors, and the children of the survivors, and the grandchildren of the survivors, to cry over the memory of the 3,500 martyrs of 1982.

In Tel el-Zaatar, nothing remains. And on August 12, 49 years after that massacre in which another 3,000 were killed – and many others are still missing – not even the survivors who were displaced first to Damour, controlled, after the 1976 massacre carried out by the Palestinians and until 1982, by the PLO; then to the northern camps of Beddawi and Nahr el-Bared, and then again to Beirut, to Mar Elias; not even the descendants of that exile personified in desperate masses with their belongings wrapped in sheets, dare to approach the concrete jungle that makes the new Dekwaneh a non-place where asking a simple question seems an affront. “We don’t know anything, we weren’t there.” And with any possibility of reconstructing the lost space removed, all that remains of the anniversary is a climatic perception. It is very hot, on August 12, in Tel el-Zaatar. And for the besieged Palestinians of 49 years ago, with water supplies blocked, the remaining fountains on the edges of the camp towards which the Phalangists were advancing, and the water in the wells polluted by the corpses that had been thrown in, today’s heat must have been far more unbearable. A song from that time goes: “Thirst besieges me, and I squeeze the hardest rocks and drink. / I suck the morning dew and lick the oil from my rifle, and my hand reaches out to every star. / And even though blood covers the road that leads to the water, I go there and drink from every wound.”

Even the new buildings, descending from the top of the decapitated hill towards the winding streets of Dekwaneh, bear no resemblance to the baraksat, the asbestos-roofed prefabricated structures that UNRWA had used to replace the tents of the first exiles back in 1952. Built on pillars to compensate for the slope, these new buildings without memory seem, to a suggestible eye, almost unwilling to touch the ground: so as not to be stained with the blood of the past.

View of the newly-built Dekwaneh from the military base on top of the hill. Credits: Valeria Rando

Warehouses, depots, sheds. Even churches. Everything cries out for reconstruction. But Tel el-Zaatar is not a place where you can cry out. It is impossible to trace the boundaries of the camp, which was less than one square kilometer at the time of the first settlement of Palestinian refugees after the Nakba – but which continued to expand with the outbreak of war and the displacement of new refugees from southern Lebanon. Yet, walking through the rebuilt city, along what must have been Tel el-Zaatar’s new boundaries at the beginning of 1976, porous like those of all camps, an eye no longer suggestible but attentive will notice that the streets of Mar Roukoz and Dekwaneh, surrounding an invisible horn-shaped area, separate two cities: towards the interior, houses with fresh plaster and well lit; towards the exterior, walls riddled with bullet holes: the architectural legacy of the civil war.

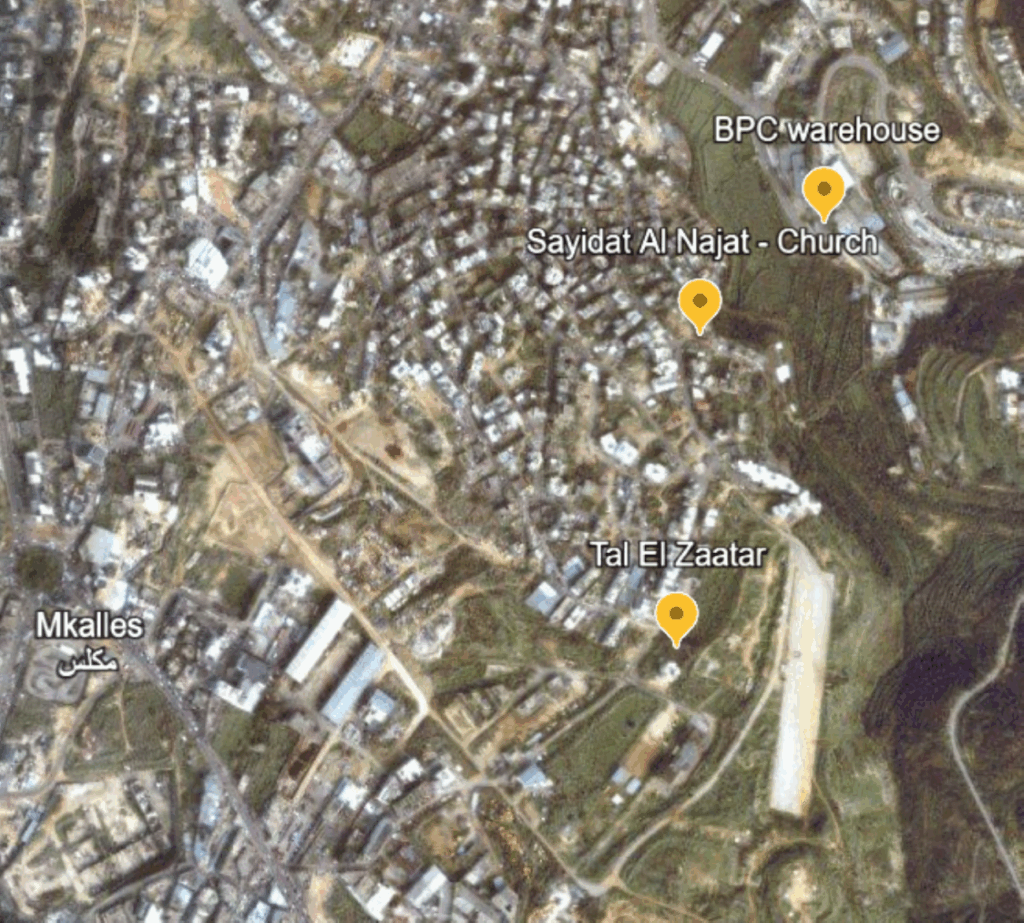

The satellite images available online do not date back further than 2000. But even so, virtually skipping 24 years of demolition and reconstruction, the violent urbanization and industrialization of the place is very clear. Two examples – the BPC warehouse and the main church of Sayidat al-Najat – undoubtedly show it.

Satellite image of Tel el-Zaatar in 2000. Source: Google Earth

Satellite image of Tel el-Zaatar in 2024. Source: Google Earth

Lost and Found: The Documents on Tel el-Zaatar

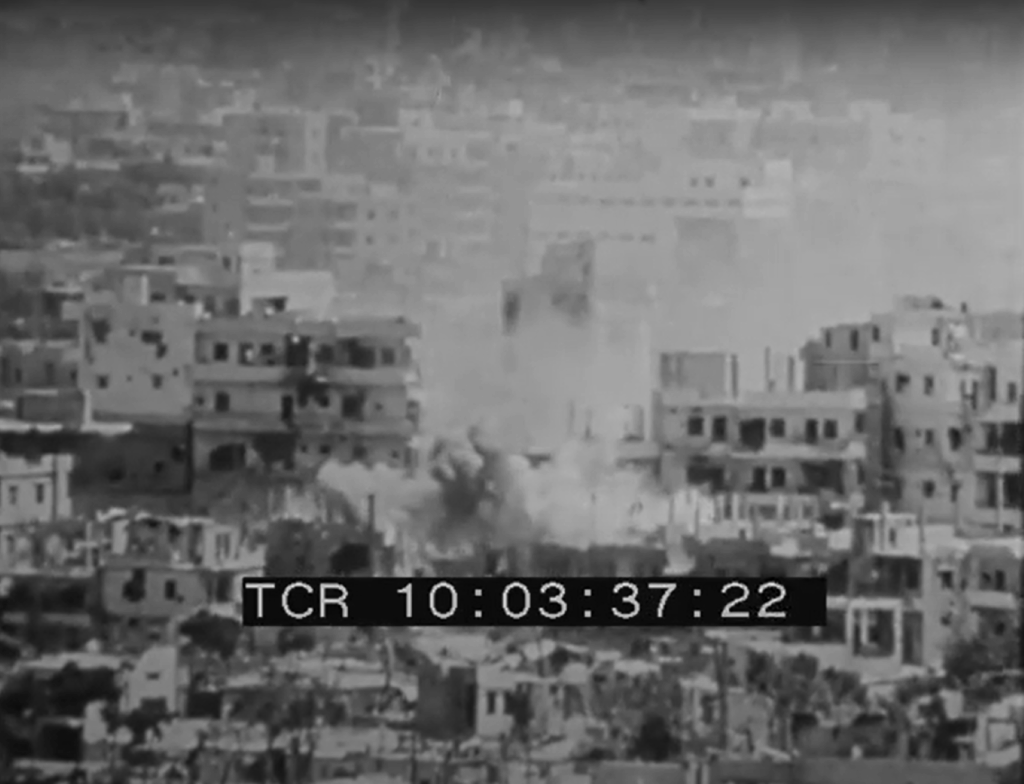

In a context of such collective removal, the surviving documents become even more valuable: among them, lost and rediscovered films, such as the 1977 film Tel el-Zaatar, directed by Palestinian Ali Abu Mustafa, Lebanese Jean Chamoun and Italian Pino Adriano. Produced in Arabic for the PLO’s Palestinian Film Institute in Beirut, in partnership with Unitelfilm – the organ of propaganda of the Italian Communist Party – all original copies of the film were damaged and lost following the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and the subsequent looting of the PLO archives.

However, an Italian-dubbed version made for television survived, and between 2012 and 2014, filmmaker Monica Maurer and artist Emily Jacir rediscovered the footage, including the original Arabic soundtrack, preserved at the Audiovisual Archive of the Democratic and Labor Movement (AAMOD) in Rome – restoring and digitizing the material to make the film available to the public once again.

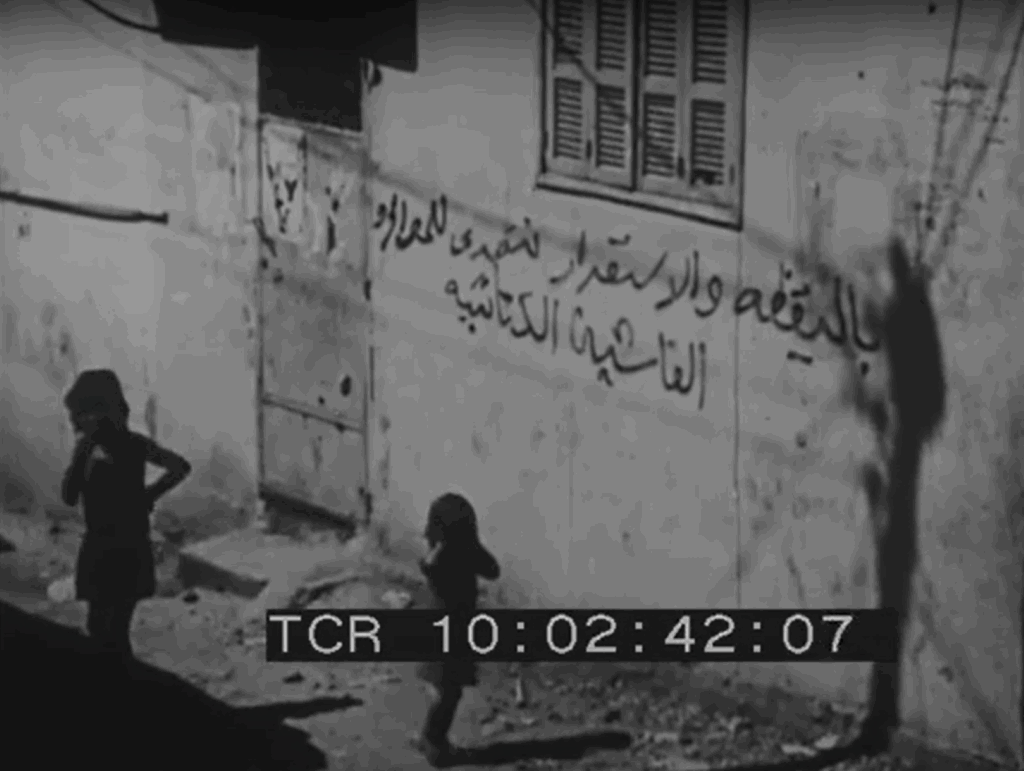

“During the 57 days of violent fighting, no camera was able to get close to the Tel el-Zaatar camp. The testimonies of the population, the combatants and the political, military and health officials of the camp, Abdul Mohsen, Salman Majid, Adam, Saleh Zaidan, Aburyad Budran, Abdul Aziz Labadie and Yusuf Iraqi, were collected at the end of August 1976.” Two sentences, before the opening credits, sum up the meaning of the film: a collective testimony to one of the most atrocious and heroic episodes in the history of the Palestinian people, reconstructed through the voices of its protagonists: the men, women and children who lived in the camp and survived the tragedy – interspersed with verses by Mustafa al-Kurd. “Thyme grows on the hill and at the foot of the hill. / Ask the wind, and you will know. / Thyme unifies time, erases boundaries, grows in water and in the desert. / Now I know why the smell of thyme is stronger than all the smells of this century drunk with death.”

Screenshot from the film Tel el-Zaatar (1977) showing a graffiti on a camp’s wall, that reads: “باليقظة والإستقرار نتصدى الموارنة الفاشية الكتائبية”, “With vigilance and stability, we confront the fascist Phalangist Maronites”. Source: YouTube

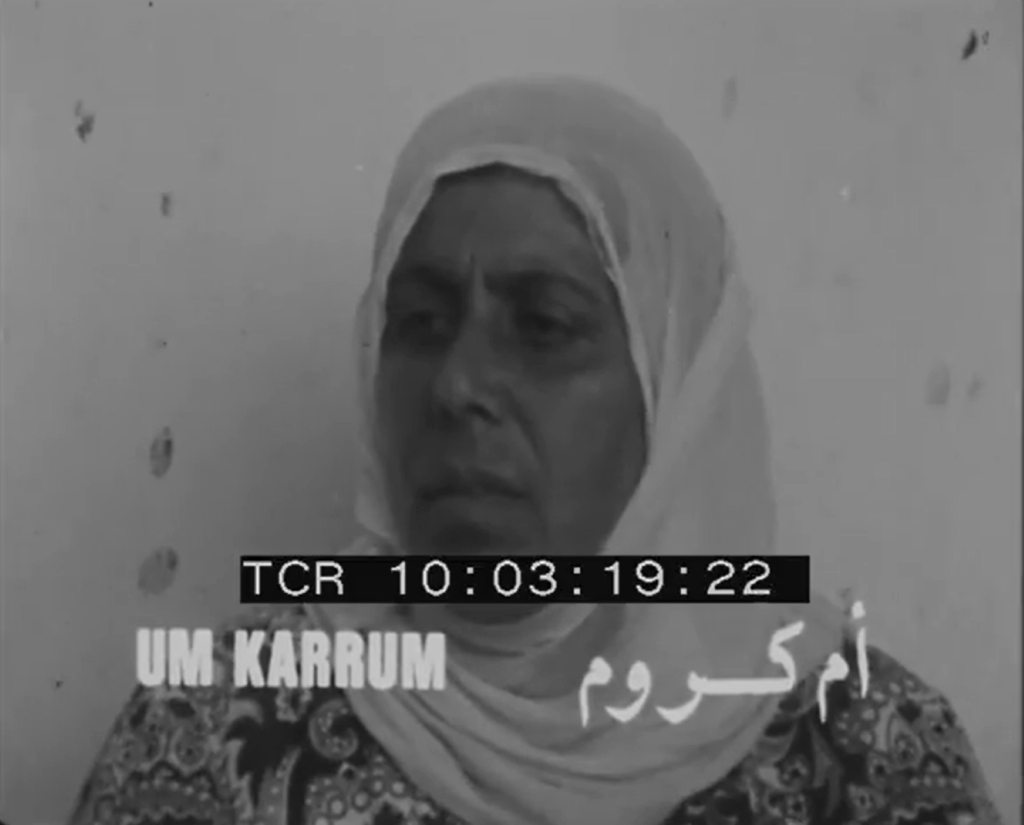

Screenshot from the film Tel el-Zaatar (1977). Source: YouTube

Before the fighting began, around 45,000 people lived in the camp, but following various firefights that killed and wounded many of the residents, and due to the increasingly tight siege, most of them emigrated. At the dawn of the final battle, around 25,000 people remained in the area, including Palestinians and Lebanese. “The enemy had impressive weapons,” begins Umm Karroum, a witness to the siege and massacre.

Founded in 1950 northeast of Beirut, Tel el-Zaatar, like many other refugee camps that sprang up around Lebanese cities, was initially isolated, but as the city expanded, it increasingly took on the appearance of a working-class neighborhood on the outskirts of the great Lebanese capital. Located close to the industrial area of Beirut, the camp provided Lebanese factories with a workforce that was forced to endure widespread exploitation: and like the Palestinians exiled in the 1950s, thousands of Lebanese who had fled the bombings in the south began to develop a consciousness – more than sectarian or national – of class.

They were all from Tel el-Zaatar the 28 victims of the Ein el-Rommaneh massacre on 13 April 1975, carried out by a team of Phalangists against a bus of Palestinian civilians returning from a wedding – with which, at least conventionally, the Lebanese Civil War broke out. Adham, sitting under an olive tree and surrounded by his comrades, says that the camp had been surrounded since then, and already in April 1975 people were beginning to suffer from a lack of food and medicine. “But the situation worsened when the Syrian regime gave the green light to the Lebanese right, allowing it to concentrate all its forces against the Tell al-Zaatar camp. The first day of violent battle was 17 June 1976.”

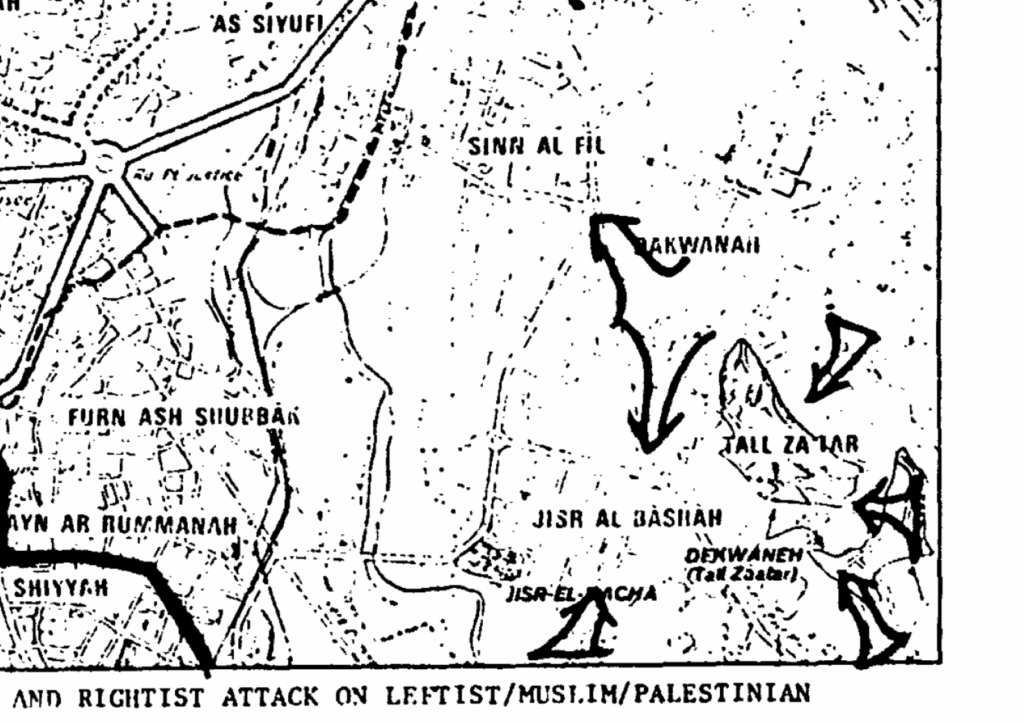

Screenshot from the Military operations in selected Lebanese built-up areas, 1975-1978, by the US Army Human Engineering Laboratory. Source: https://web.archive.org/web/20140201161520/http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/b040213.pdf

The Ein el-Rommaneh massacre’s bus exhibited at Nabu Museum for the 50th anniversary since the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War. Credits: Valeria Rando

Abu Imad continues: “The attack began at 8 in the morning in the Mkalles area. We were occupying advanced positions directly below Mansourieh, and the distance between us and the enemy was about 70 meters. We noticed that they were concentrating forces and armored vehicles,” he explains, while asking to film Ali Khanjar – one of the four in those positions, at the foot of the thyme hill. He describes him as legendary. “They attacked us and we repelled them,” says the fighter, simply. “To recover their dead, they started bombing us. With our firepower reduced to a minimum, we could no longer respond with the same intensity, and we began firing one shot at a time. After a few hours, other fighters arrived, some died on the way, others were forced to seek shelter in factories, a few arrived with ammunition, so we continued to fight. There were more than 20 attacks in three hours.” And he continues, proudly: “I am Syrian, a master carpenter, and I have been participating in the Palestinian revolution since 1971.”

Screenshot from the film Tel el-Zaatar (1977) showing legendary fighter Ali Khanjar. Source: YouTube

According to Abdul Mohsen, on the first day, around 8,000 artillery shells were fired, all concentrated on what was considered the center of the camp, the inhabited area, while the resistance positions were located on the border. “Immediately,” he says, “communications between us and the general command were interrupted. Water supplies were also cut off. Only the fountains located on the edges of the camp remained.” In addition to the well polluted by the corpses that had been thrown into it, another well – dug by the doctors of the Palestinian Red Crescent – could not be used because there was no fuel for the pump motor. “So there were a total of five water sources for 25,000 people.”

“Fortunately, the civilian population did not leave the shelters,” confirms Dr Labadie, “and in fact no civilian casualties arrived at the hospital that day. On the first and second days, the population was very shaken by the violence of the attack, because they did not understand the reasons behind it. But over time, the plan became clear. We were waiting for help from the west that never arrived, so people gradually got used to the constant attacks, and we became convinced that Tal el-Zaatar was caught in an iron grip.” The attacks did not stop after the first or second day, but continued unabated: bombings, machine guns, snipers stationed on the top floors of the buildings overlooking the camp. “Every movement was impossible,” Labadie continues.

The attack was led by the National Lebanese Party (PNL), with the support of other Christian militias and splinter groups of the Lebanese Army. The Kataeb only joined after June 27. For 57 days, the militias launched more than 70 attacks, using 155-millimeter mortar shells – sometimes at a rate of three bombs per minute – and resorted to a few dozen armored tanks. When Tel al-Zaatar fell, between 2,000 and 3,000 Palestinians were killed; some were summarily executed, including a number of them who had already evacuated the camp and were reaching West Beirut. Many bodies were mutilated, a number of women were raped, and some – particularly children – died because of the shortage of medication and water. This was the largest massacre in the war that was yet to happen. After the attacks, the Lebanese Forces (LF) came into creation, with Bachir Gemayel as its president, representing the Kataeb, and Dany Chamoun, representing the PNL, as vice president.

Screenshot from the film Tel el-Zaatar (1977). Source: YouTube

A young woman, Marie Haddad, holding her little sister in her arms, coldly recounts the raids to the cameras. “First, they stole the money and the rings. Then they separated the men from the women. Right before our eyes, they took away twelve boys and three old men, led them behind a wall and machine-gunned them. They told us they only wanted to interrogate them, but they didn’t even spare the old men. As for us women, as we went down into the shelter, we heard them shouting, ‘I want the girls!’. They took my other sister away.”

Left orphan, the little girl recounts: “Mum climbed over the corpses and lifted them up to see if my brother was among them. They couldn’t find my father, Abu Labib. Because my mother was screaming, they took her behind a wall and killed her too. And when I asked about her, they told me, ‘Do you want to see your mother? We’ll show her to you now.’ They wanted to kill me on top of her. My sister Marie pulled me back and saved me.” When the journalist asks the girl who they were, she replies, simply: “The Phalangists.” And what were they like, continues the voice behind the camera. “They had beards, long, messy hair, and were bare-chested,” she replies.

Witnesses tell of a race against time to transfer the wounded as quickly as possible: ladders, doors and mattresses were used instead of stretchers, while the Red Cross was repeatedly denied access to the camp. The bombing was so intense that it was impossible to bury the bodies. At the gates of the camp, a Palestinian woman waits impatiently for the wounded to be evacuated. “Every time they say they’re coming, I come here to the museum to wait, but they don’t arrive. I pray to God that they will be found alive. If the Phalangists truly believed in God, in Christ, in the Holy Virgin and in creation, they would know that human beings were created to live in the universe, not to be persecuted. They must accept us in this country. We have been welcomed for thirty years and they must continue to accept us. No country since the creation of the world has committed such a criminal act as this one here in Lebanon. Lebanon is the most criminal country of the isolationists, because we are a people like them. They must fight with us to reconquer Palestine, not against us to kill us on Lebanese soil, as they have written on the walls: ‘This will be the tomb of the Palestinians’. No, they should not hope for that, because for every Palestinian who dies, a thousand will be born, and we will continue to fight to liberate Palestine.”

After being refused five times, the Red Cross delegation of doctors and nurses was finally able to enter the camp to evacuate the wounded, thanks in part to external pressure. They were searched at the entrance and even had their cigarettes confiscated for fear that they would be given to those under siege. On August 3, 91 wounded people were evacuated from Tel el-Zaatar; on August 4, another 243; and 74 on August 6. But as soon as the ambulances left, the besieging forces resumed shelling and shooting.

Screenshot from the film Tel el-Zaatar (1977). Source: YouTube

Meanwhile, the Phalangist teams advanced, occupying new positions and gaining ground, getting closer and closer to the water sources and reducing the besieged population’s access to them. On August 7, Umm Samir was shot in the arm while filling her water tank. She survived, but could only hope that the blood would not contaminate her children’s source of survival. Fatima was one of two survivors of the massacre at the fountain on the same day. “There were dead bodies in the street,” Mohammed Abdu tells the camera. “When a woman fell or was wounded in the teeth, hand or foot, she never abandoned her tank, because she had to bring water to her children. Several times I saw dead women still clutching full water tanks in their hands.”

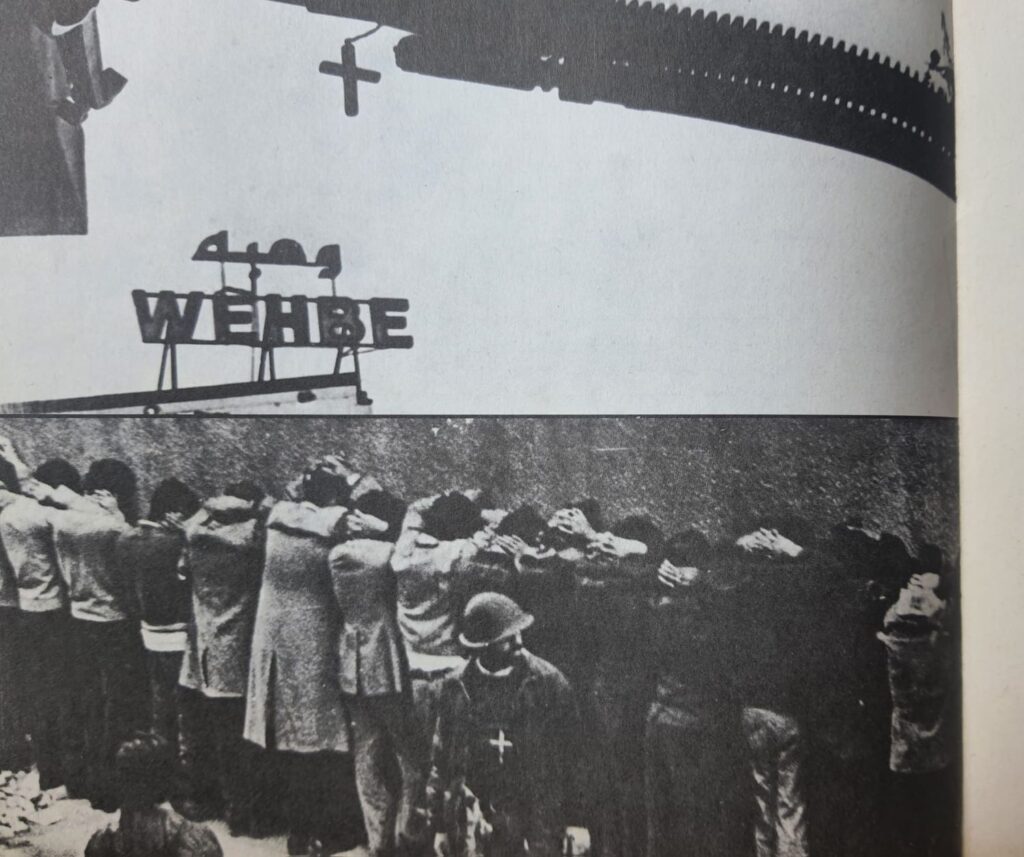

On August 11, the last position fell with the last water tap in the camp, and the general command decided to evacuate the civilians, while the fighters would leave via the mountain side. You cannot fight thirst with guns, after all. So they sent a delegation of elders from the camp to negotiate with the Phalangists in Dekwaneh, represented by Bashir Gemayel. They agreed that there would be no massacres, that it would be a surrender. The civilians were supposed to begin evacuating the camp the next day at 2 pm, but on the morning of August 12, they were surprised by the enemy forces entering the camp. “The bombing was very violent, the shooting relentless. When we reached an open space, they stopped us and grouped us together. Ten steps – I counted them – to a barbed wire fence that I knew meant death. I begged a Syrian officer to do something, he only replied: ‘Think of yourself’,” says Dr Iraqi, who survived his nurses, shot one after the other. “We in the command remained in the camp to face them until evening. At sunset the next day, when the camp had been completely evacuated of civilians, our group, 106 of us, took to the mountains. It took us three days and three nights to get out, and many died along the way.”

What follows is a gruesome description of the massacre of civilians evacuated to Dekwaneh. Phalangists, Guardians of the Cedar (Hurras al-Arz), members of Barakat’s army, the Armée du Liban Libre (ALL) – all of whom joined together in the Lebanese Forces. “They are traitors,” condemns Umm Karroum, who saw everything. “They jumped on old people and children and knocked them unconscious. Once they passed out, they tied them by their feet to a rope – two by two, to the rear of cars speeding towards Jounieh. Ten, twenty cars left. They tied an 80-year-old man’s one leg to one car, the other to another, and literally tore him in half,” the woman recalls. “Groups of women dressed in black armed with sharp glass bottles hurled at the unarmed evacuees, immobilized by their men.” Men who kidnapped girls and young women, who searched old women thinking they were hiding money. And for the people who threw themselves into the streets in agitation: summary executions.

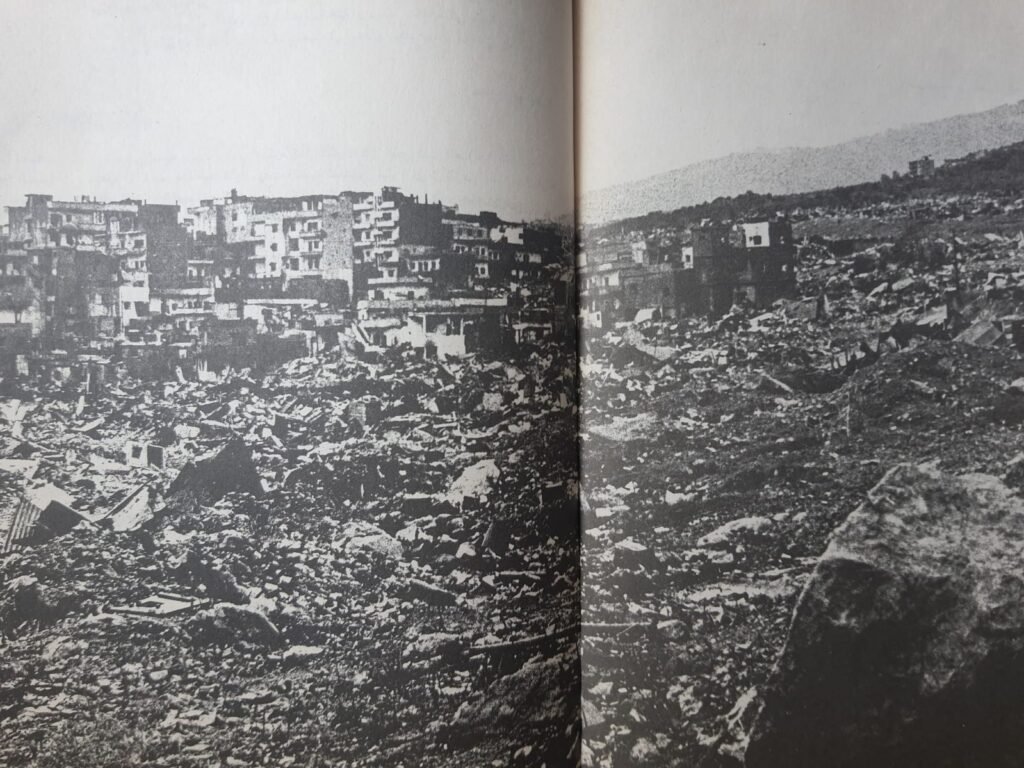

What remains are the images collected by the journalists of the Associated Press, the mountains of corpses in the streets, the destroyed camp: and the archaeological attempt to piece together the debris and give voice to the survivors.

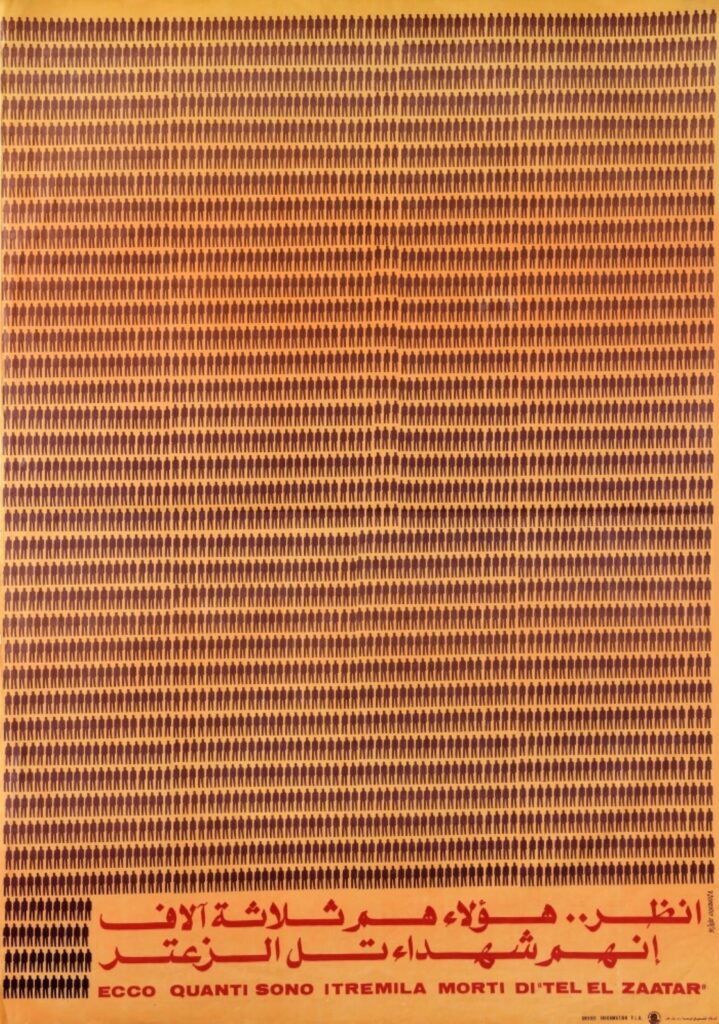

Poster realised by Italian journalist Viviano Domenici, reading: “Here’s how many are the 3000 dead of Tel el-Zaatar”. Source: Palestine Poster Project

An Archaeological Endeavour: Tariq Tel el-Zaatar

“Today, nothing remains. No one remains in the tents of the Galileans. So, I prepared this text as an archaeologist would. I propped up the walls and arches, but the colors are too pale. And turmoil, and forms of sadness, and countless emotions. I became more convinced: no work surpasses the living event. Writing is an apology. And a necessary apology.”

It was written by Hani Mandis in the introduction to his palimpsest: Tariq Tel el-Zaatar, the road to Tel el-Zaatar – or perhaps the road, from Tel el-Zaatar, to Palestine – which in the aftermath of the massacre, the author described as shorter. And as his friend and colleague Mahmoud Darwish wrote in the same months, dedicating to an anonymous Ahmad Zaatar the legacy of survival: “I am the Arab Ahmad / He said / I am bullets / and oranges / and dreams / Tel Zaatar is my tent / And I am the homeland / The ongoing journey / To the homeland”. Yet with no heroization.

Writes Mandis in the introduction to what remains one of the rarest documents on the massacre to date – a collection of interviews with survivors, conducted together with artist Mona Saudi: “Their collective moments, with simplicity, freedom, and strength – as they lived them during the siege and the fighting – offer me clear excuse and consolation: that the true author is the people of Tel al-Zaatar, speaking here through the inspiring model of struggle which, with fearless insistence, paves the way for the people’s war on the new revolutionary land before us.” And indeed this is the case: after the opening lines, the humble voice of the author-archaeologist disappears, replaced by the choral but extremely precise voices of the survivors recounting the siege.

Preceded and echoed by an opening note – once again, the voice of Mahmoud Darwish – it reads: “Let those who erect barricades from their own remains return to their true hobbies, and let Tel al-Zaatar speak about Tel al-Zaatar. They alone have the right to speak, these words belong to them. And you will find in their words writing that negates writing, to learn the alphabet of honesty and art from this simplicity.” And he continues: “You wonder about the point of writing, and you continue to ask, so that we may ask about the point of life itself. Yes, we doubt everything. You will doubt life because of how many of them have died. No ink, no ink, not enough to imitate their blood.”

But it is their language that changes – not that of poets, but of survivors: even though it is the poets’ task to immortalize their names. Those people as firm as buildings, aware that they were going to die, hungry and thirsty, and yet decided to stay: ‘We believe,’ they told the fighters. But just as the hero is the last to know he is a hero, Tel el-Zaatar, at that time, did not know Tel el-Zaatar – and Mandis and Darwish, in between, did not know how to name it, for Tel al-Zaatar has many names and no name. Writes Darwish: “Today is Tel al-Zaatar. And Tel al-Zaatar gathers its misery and stands on the summit of the details it hides, preserved by those who know and those who do not know and those who do not want to know.”

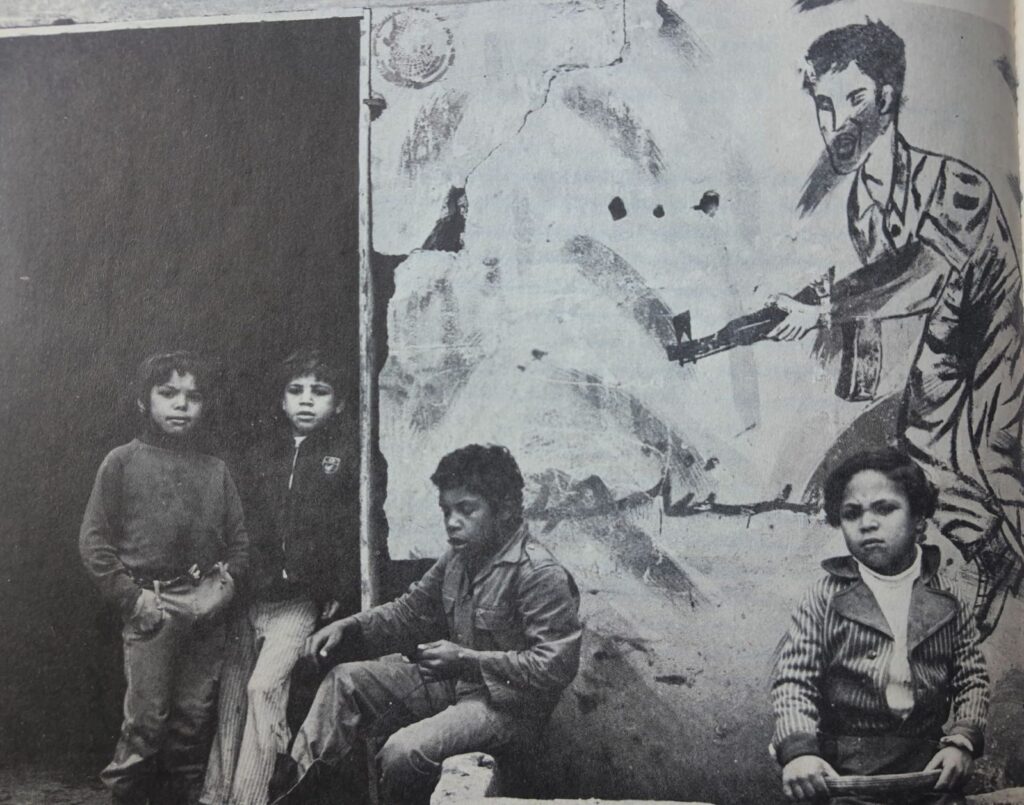

Children of Tel el-Zaatar. Source: Tariq Tel el-Zaatar

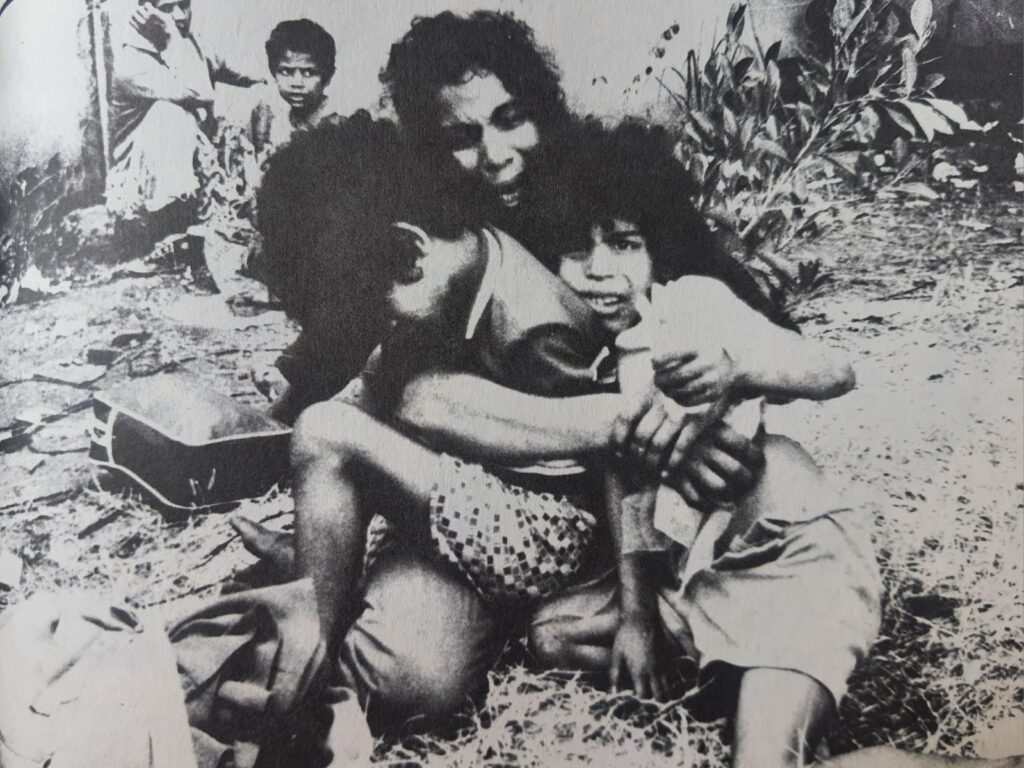

Children in a moment of despair during the most acute phases of the siege of Tel el-Zaatar. Source: Tariq Tel el-Zaatar

Even today, many people don’t know, some – don’t want to know. And the story of documents of this caliber – out of print, aged, kept, as in this case, by the author who jealously lent it to me – shows that it is not enough to have written: we must continue to talk. To search for Tel el-Zaatar, even if nothing remains of Tel el-Zaatar. Even if it is in the futility of an anniversary. Every August 12, think of Tel el-Zaatar. Say Tel el-Zaatar. The poet is an archaeologist and restorer. Today’s citizen is a sounding board.

Mandis continues: “Any superfluous talk here, any personal effort – no matter how important – is nothing but a restorative effort. And any celebration of any effort is a kind of insufficient participation, yet still necessary, in the battle of Tel al-Zaatar. And it must remain impregnable from oblivion: because a people who lose their memory and forget their experiences cannot win.” Echoes Darwish: “And because Palestine is not a whore, and because it does not reside in a room, it will not be everyone’s beloved. It is everyone’s struggle. And a small name like Tel al-Zaatar becomes a crossroads for all directions. And by way of Tel al-Zaatar, by way of revolution, you reach Palestine and its sisters. Oh, oblivion: you are worthy of all names, but you will never be Tel al-Zaatar.”

A picture of the camp before the destruction. Source: Tariq Tel el-Zaatar

A picture of the camp after the destruction. Source: Tariq Tel el-Zaatar

A group of men from Tel el-Zaatar stand in line against a wall, waiting to be shot by the Phalangist firing squad. Source: Tariq Tel el-Zaatar

The Language of the Other Side

If memory is fragmented, if piecing it together is truly an archaeological endeavor, the statements made by the other side cannot be ignored. On August 15, 1976, three days after the massacre, the new leader of the Lebanese Forces, Bashir Gemayel, addressed foreign journalists saying: “Well, we are very proud to have you and we are also very proud to let you visit Tel el-Zaatar. But we are also very sorry to let you see what you are going to see now, because we know very well that the situation in Tel el-Zaatar is not very clear, not very quiet, and not absolutely peaceful. You will see some séquelle, some consequences of 16 months of very heavy fighting, and the consequences of the pressure against Dekwaneh, under siege from Tel el-Zaatar for nine or ten years.”

Two months later, on October 9 of the same year, Gemayel himself, proudly dressed in his military uniform, stated to the press: “We have cleaned more than 40 square kilometers from the heart of Lebanon and we are willing to do more and more in the future, because we believe that every step that we are doing to clean is a step that is taking us further and further from the idea of the partition of Lebanon. Now it is not the turn of West Beirut, it’s too early to say what will be the next target. But it is the time to say that the final target is to have one Lebanon free and clean of any foreign political and military présence. If they would like to stay in Lebanon they might be welcome, but not as a political force or as a military force.”

Gemayel would have contradicted himself six years later, the day after his assassination, when his men entered Sabra and Shatila and massacred thousands of unarmed civilians, after Sabra and Shatila had already been stripped of any political and military presence. Once again, the Palestinians were not welcome, and the time had come for West Beirut to become the target.

Phalangists’ leader Bashir Gemayel speaks to the press after the fall of Tel el-Zaatar (August 15, 1976). Source: AP Archive

I attempted to interview Fouad Abu Nader – Head of the Lebanese Forces in 1984-85 and member of the Kataeb Political Bureau from 1986 to 1992 – about the massacre that part of Lebanon still refers to as “the events of Tel el-Zaatar.” He declined to make any statement. Through the voice of the communications coordinator of the numerous NGOs that he founded and directed alongside his political career – among them, Arc-En-Ciel Rehabilitation of the Handicapped, Jeunesse Promesse, Eastern Christian Assembly, and Nawraj – Abu Nader made clear that “unfortunately, he is not available for any interview for the time being. He doesn’t want.” And when I asked for the reason, the communications coordinator replied: “He didn’t mention it. He has been away from all interviews for a while now and he is not ready to resume his public intervention. He doesn’t want to talk to you nor anyone else on the matter. It’s been a while now.”

The so-called other side needs to be named because it bears responsibility for 3,000 deaths, and for those families who, despite having stopped asking for it – since it is for survival that they’ve been fighting for – deserve to see those responsible held accountable.

Opposite, the side of the murdered, mutilated, raped and oppressed needs to be named for it is through their names that survival flourishes – in memory. Informal conversations with survivors, lost and rediscovered documents, the powerful poetic voice of Hani Mandis and Mahmoud Darwish – all bear witness to this side and agree on one thing: a massacre was committed in Tel el-Zaatar.

Yet the two camps speak specular languages. That of the executioners: rigid, obscure in its emptiness, almost untranslatable because it is entirely focused on alluding to phenomena without naming them – and that of the victims: photographic, immortalizing and petrifying, without beating around the bush, limiting itself to describing and denouncing: 49 years ago, a massacre was committed in Tel el-Zaatar.

A statue of the Virgin Mary stands on the former site of the Tel el-Zaatar camp. Credits: Valeria Rando