Recovered archaeological items from Switzerland mark a significant milestone in Lebanon’s efforts to reclaim its smuggled cultural and historical treasures

While Solidere’s archaeological crimes have revealed a 35-year-long history of heritage demolition, and Israel does not seem to cease its urbicidal and patrimonicidal campaign against historical sites in south Lebanon and the Beqaa Valley, a positive step in Lebanon’s ongoing effort to reclaim its cultural heritage has finally been made: three ancient artifacts illicitly taken out of the country and later seized by Swiss authorities have recently returned home. The items, handed over by the Swiss Embassy, included a blue-tinted glass bottle adorned with embossed motifs, a small statue of the goddess Aphrodite dating back to the second-third century BC, and a small bronze statuette dating back to the second century BC.

The successful recovery was made possible through the collaborative efforts of the Ministry of Culture, the Directorate General of Antiquities (DGA), and the Lebanese Embassy in Switzerland, which has been actively addressing issues related to Lebanon’s national heritage. “This initiative reflects our dedication to preserving Lebanon’s rich cultural legacy and safeguarding it from illicit trade,” stated the Director General of Antiquities, Sarkis Khoury. At the same time, the Minister of Culture Ghassan Salame, reappointed twenty-two years after his previous term, emphasized its commitment to combating illegal trafficking and securing the return of as many artifacts as possible to their rightful place in Lebanon: a process that underscores the critical role of international collaboration in protecting cultural property.

As part of the Culture Ministry’s “mission and role in combating illegal trafficking in archaeological artifacts,” Lebanese archaeological pieces that were stolen during the country’s 15-year-long Civil War have been progressively taken back home: in 2008, for instance, the United States returned several antiquities that had been looted from Lebanon – among them, the Metropolitan Museum of Art returned pieces like a Roman-era statue of the goddess Athena, illegally exported and sold to collectors; France, another country that has seen many Lebanese antiquities in its museums, returned a Phoenician statue to Lebanon after years of legal wrangling in 2017; in February 2018, then, five archaeological items stolen in 1981 from the Byblos citadel’s storerooms, which were located in the United States and Germany, were repatriated; in April 2020, the then-Culture Minister Mohammad Mortada confirmed the existence of an archaeological piece with the number E1787, a marble head from a young Roman, originally found during the excavations of ‘World Dunan’ in 1971 in the Temple of Ashmun, the Phoenician god of healing, in Saida – and illicitly located in the possession of Royal Athena Galleries in New York; while in September 2021, nine mosaics, a Roman head, and a bronze were recovered from the collection of antiquities dealer Georges Lotfi.

The Lotfi case

Back then, “information was also received by the Culture Ministry in Lebanon indicating the presence of twenty-two mosaic pieces in New York in the possession of an individual named Georges Lotfi. These pieces were stolen or illegally transported from Syria and Lebanon to the United States. Investigations were ordered to determine the source of these pieces. Upon careful examination of the matter, and following intensive efforts by the Culture Ministry through the General Directorate of Antiquities, it was confirmed that nine of these pieces originated from Lebanon and were seized by an antiquities dealer,” a statement released by the DGA read. In March 2023, the relevant authorities in the United States confirmed the discovery of two additional pieces also originating from Lebanon.

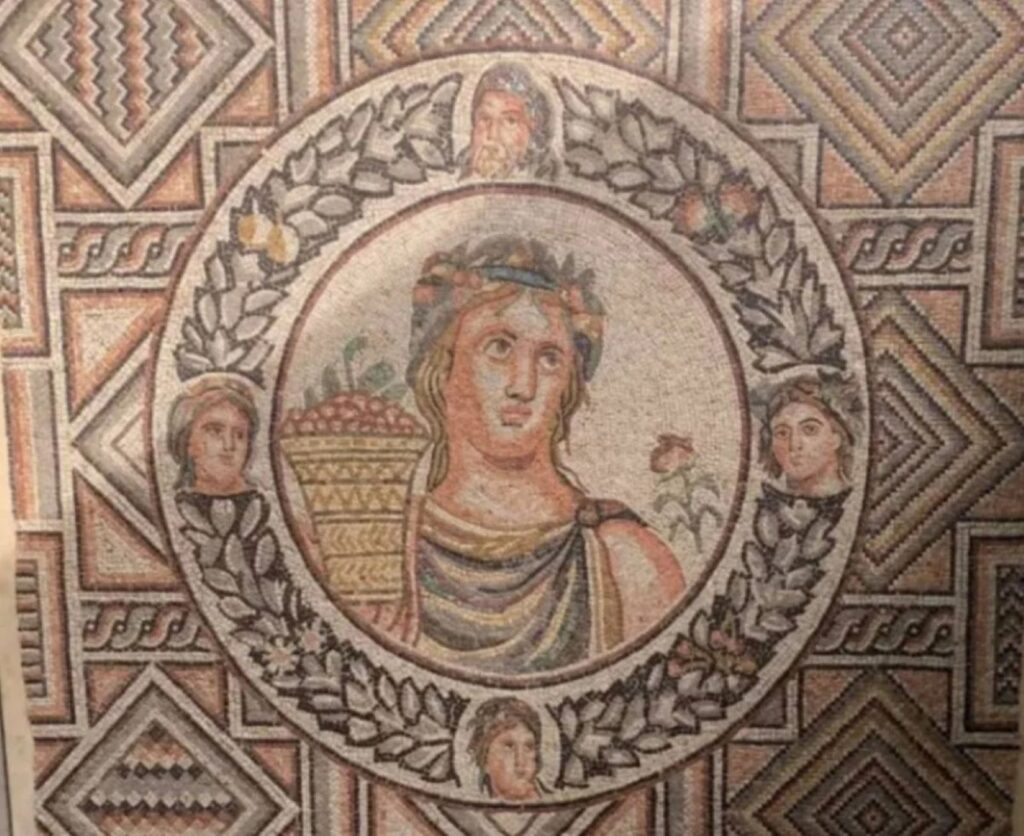

An ancient mosaic showing a personification of autumn, allegedly illegally removed from Lebanon in 1987. Courtesy of New York District Attorney’s Office. Source: L’Orient-Le Jour

A couple of months later, on June 5, 2023, INTERPOL – the International Criminal Police Organization -, following the decision of Banque du Liban’s then-Governor Riad Salameh, issued a red notice for the Tripolitan collector and retired pharmacist, Georges Lotfi, then 82 years old. Known for having previously collaborated with US justice as an informant on several high-profile antiquity seizure cases, his name was added to the list of Lebanese nationals – now nine – that INTERPOL has requested to provisionally arrest, pending extradition.

The notice came after a criminal court in New York issued an arrest warrant against Lotfi, charging him with the possession of looted antiquities on March 8, 2022. The court charged Georges Lotfi of stealing a total of twenty-four antiquities that he exported to the US in 1988, thirty-four years earlier: twenty-three mosaics from Syria and Lebanon and a 1,500-pound limestone statue that the affidavit says originated from the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra. All items carried the same “fabricated generic provenance,” according to Homeland Security Agent Robert Mancene, and were seized in New York in 2021. The investigators allege, however, that “several” other mosaics are still on the market or in the collection of New York’s prestigious Metropolitan Museum (MET).

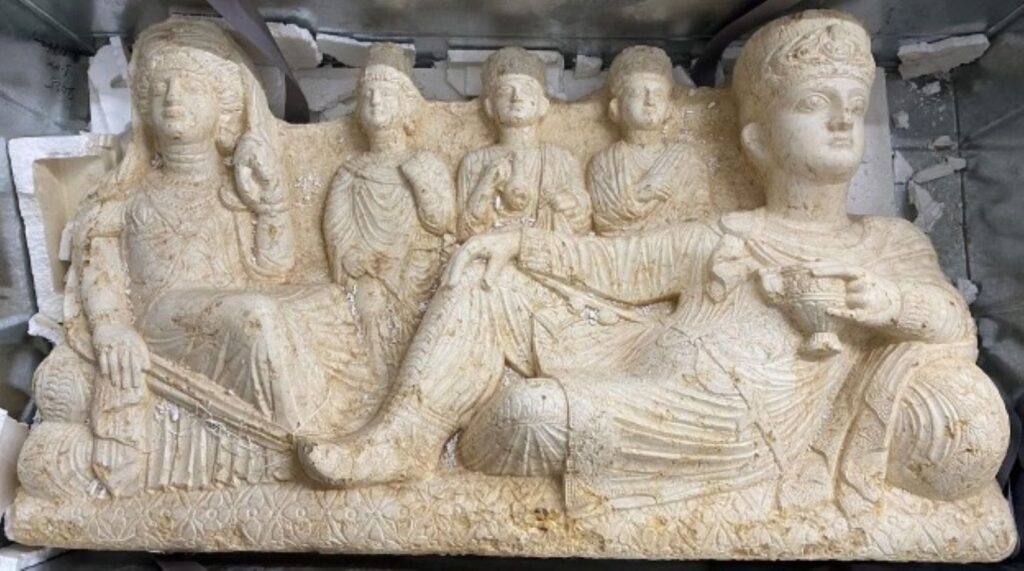

Sculpture of a man, his wife and children, thought to be from Palmyra, Syria. Seized from Lotfi’s storage. Courtesy of Manhattan District Attorney’s Office. Source: Cultural Property News

Lotfi, who currently lives in Lebanon, refuted these accusations. At the time he told the press that he himself “declared the antiquities in question to the US authorities” in 2021, when he wanted to lend them to the MET for a temporary exhibition. “I was the one who declared them to the authorities and asked the US Attorney’s Office to inspect them in my office in New Jersey,” he said to the Lebanese daily L’Orient-Le Jour, adding that this was a standard procedure in the US. It is in fact true that in 2021, Lofti, a frequent collaborator of Matthew Bogdanos, head of the Manhattan district attorney’s Antiquities Trafficking Unit (ATU), and Mancene himself, invited investigators to view antiquities held in his storage unit in Jersey City, according to an affidavit accompanying the arrest warrant. “Based on my conversations with the defendant over the last several years,” the Homeland Security Agent wrote in the affidavit, “I believe the defendant thought he had laundered the antiquities so well and had created such good – albeit false – provenance that he did not think the ATU would be able to determine their true origin.”

The affidavit details how a tip from the dealer led to the confiscation of the gilded Coffin of Nedjemankh, dating back to the 1st century BC, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019: the ornamented artifact was the centerpiece of the exhibit, Nedjemankh and His Gilded Coffin, which shuttered early after investigators determined that it had been plundered from a tomb in Egypt. The seizure of the coffin has infamously triggered an ongoing international investigation into 56 million dollar-worth of looted Egyptian antiquities sold to the Louvre Abu Dhabi and the MET. Meanwhile, as the affidavit alleges, Lofti was participating in the smuggling of antiquities from war-torn regions of Syria, Lebanon, and Libya – including a 12-million marble bull’s head.

Lotfi had claimed one of the prosecutors threatened him several times with legal action if he did not hand over the twenty-four items to the US authorities – yet he refused to comply. “I had bought the art pieces from Lebanese antiquities dealers licensed by the General Directorate of Antiquities in Lebanon,” he said, adding that he had “exported them to the US to keep them safe” from the turmoils of the Lebanese Civil War.

In an open letter published on his personal website, mentioning Lebanese and international laws – namely, Regulations No. 166/1933, UNESCO Convention of 1972, Decree 3065 of 12/3/2016 corroborated by the decision of the Ministry of Culture No. 52 of 6/4/2022, as well as the Lebanese Regulation No. 166/1933 -, he claimed they “converge entirely in admitting the right of individuals to possess antiquities, in accordance with common law and regulation of the profession of art dealers.” The letter continued: “it should also be noted that Lebanese law gives the right of individuals to the acquisition of classified antiquities, i.e. officially listed in the official public registers of the Lebanese State, excluding unclassified antiquities, with the right of the curator of the National Museum to inspect their place of detention and restoration, according to the state of the art.” In fact, modern Lebanese regulations on antiquities go even further, exempting holders of movable antiquities from proving their origin and method of acquisition – as stated by the Decree No. 3065 of 12/3/2016 under the aegis of the Minister of Culture Raymond Arayji, corroborated by Ministerial Decision No. 52 of 6/4/2022 of Minister Mortada.

Moreover, the penal regulations – included under Articles 730, 731 and 227 of the Criminal Code – impose to citizens and holders of antiquities the obligation to “protect them from any destruction or even deterioration, and exempt from any actions taken by their holder with a view to their preservation, because of unavoidable force majeure jeopardizing their sustainability.” The Hague Convention of 1954, to which Lebanon acceded in 1954, is in line with the same rules.

Citing these cases, Lotfi pronounced his J’accuse: “In 1975 the Civil War in Lebanon began and my premises were bombed, and some pieces destroyed, so I decided to take out part of my collection, and shelter it in Europe and the United States. This has been done legally, through an accredited shipping forwarder, known worldwide,” the English version of his lettre ouverte reads.

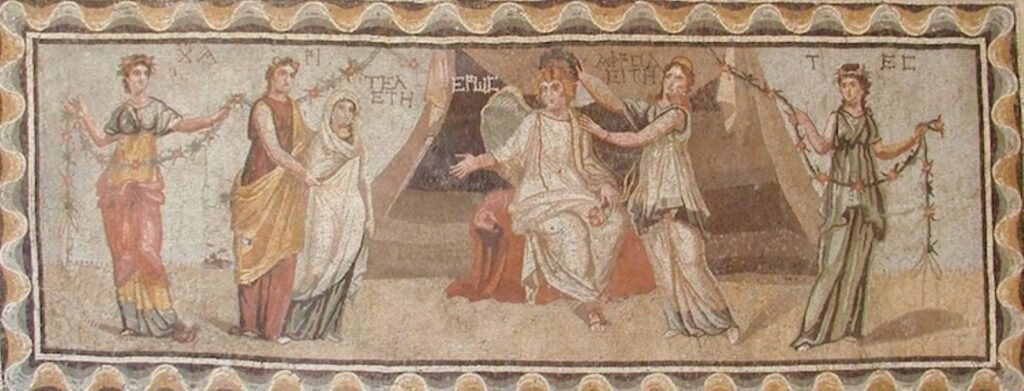

Mosaic seized from Lotfi’s storage. Courtesy of New York District Attorney’s Office. Source: Cultural Property News

Lotfi Telete Mosaic, seized from Lotfi’s storage. Courtesy of Manhattan District Attorney’s Office. Source: Cultural Property News

This, though, has not convinced the American court. According to the New York-based investigators, Lotfi did not apply for a permit to export the artifacts from Lebanon, thus violating Lebanese law, which stipulates that it is illegal to export any human-created objects made before the year 1700 CE from Lebanon without a permit. Moreover, investigators contend that Lofti’s widely-known expertise on illicit trading ultimately was his downfall. Knowing the markers of a looted object, he couldn’t claim ignorance to the issues with the provenance of the antiquities he purchased. Among the evidence against Lofti, in addition, are photographs he displayed to agents that show the pieces “with encrustations” at the time of their acquisition – while legitimate excavations involve cleanings of any notable findings.

“In any case, the charges against Georges Lotfi are statute-barred, as he claimed to have made his acquisitions more than 30 years ago,” Lotfi’s lawyer, May Azoury, claimed – despite the US law considering the criminal act to be continuous, not punctual: hence the statute of limitations running when the illegal possession ceases, not when it begins.

Regarding the feasibility of returning artefacts to their homeland, back in June 2023 former Minister Mortada told L’Orient-Le Jour that “the decision on the possession of items applies only in cases where there are no suspicions about their origin.” “However, we have proof that the mosaics exported by Mr. Lotfi were stolen,” the Minister said, without giving further details, yet adding that “we have notified the US justice system that the items in question are the property of Lebanon and the Lebanese, and we asked for them to be returned.” However, the US authorities have not yet complied with the ex-Culture Minister’s request. The Associated Press quoted a Lebanese judicial source as saying that the US authorities “said they would repatriate the antiquities to Lebanon on condition that Lebanese authorities put Lotfi under arrest.” “This is false news,” said the Minister, explaining that US justice intends to temporarily keep the items for evidence in the American proceedings, while the US embassy in Beirut refused to make any comments on the ongoing investigations.

War, crisis, and illicit trade’s trajectories

However, the Lotfi case was not just an isolated incident; it was part of a larger pattern of illegal trade and smuggling of cultural heritage from Lebanon, especially following the Civil War – the chaos of the conflict making it easy for looters to access ancient sites and smuggle treasures abroad. In this regard, another case – the one involving the Swiss Embassy, recently re-emerged in the news as one of many incidents that highlighted the scale of such a problem – is part of the much broader issue of illicit trade of cultural properties in the region. Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, numerous Middle Eastern countries, especially Lebanon – with its rich history as a cradle of Phoenician civilization, later fell under Roman rule -, have notably struggled with the looting and illegal exportation of archaeological artifacts.

Precious antiquities taken from the archaeological sites of Tyre, Byblos, and of course Baalbek, have been part of a fifty-year-long illegal trafficking network, with the main issue being their questionable provenance and the ownership claims: some of the antiquities have been transferred to official institutions – in the case of embassies, protected by the diplomatic immunity – by private collectors, others might have been part of ongoing transactions involving middlemen or dealers.

As a matter of fact, the Lebanese Civil War, and, more recently, the Syrian one, created conditions ripe for looting: during these conflicts, war profiteers and militia groups looted historical sites and transported the artifacts abroad, often selling them through illegal channels or at auction houses. However, the illicit antiquities trade is a multibillion-dollar industry, involving not only militiamen and armed groups, but private collectors, art dealers, and official institutions that may acquire items without thoroughly verifying their provenance or their history of ownership. In fact, while some museums and auction houses have played an active role in combating the trade of looted artifacts, there have been numerous high-profile cases where major institutions have been implicated in the sale of stolen goods, which, in some cases, remain unidentified for years.

Repatriation efforts, a long path ahead

As global awareness increases, international laws, diplomatic negotiations, and the cooperation between governments and institutions like UNESCO are crucial in protecting humanity’s shared heritage. However, for the time being, it is still hazardous to pinpoint an exact number – that some estimates around thousands – of archaeological artifacts from Lebanon that are currently abroad, as these numbers are constantly shifting due to ongoing research, legal actions, and international efforts to repatriate stolen cultural properties. Moreover, many items are still not properly cataloged, making tracking difficult.

Despite the increasing international laws on Cultural Property – in this regard, UNESCO and INTERPOL have both played significant roles in helping Lebanon and other countries recover stolen artifacts – the challenge remains that many objects were taken before these international laws were in place, and that often, as in the case of the UNESCO Convention, enforcement is tricky and often depends on international cooperation. Today, museums in Western countries like France, the United States, Italy, and the UK house many Lebanese artifacts. The Louvre Museum in Paris and the British Museum in London are particularly well-known for having large collections of Lebanese artifacts, especially from Phoenician and Roman times – together with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Italian Archaeological Institute in Rome.

“Walking into any Western museum today, you will see the curated spoils of Empire, sitting behind plate glass: dignified, tastefully lit. Accompanying pieces of card offer a name, date and place of origin. They do not mention that the objects are all stolen.” These are the words of Professor Dan Hicks’ The Brutish Museums – a book standing at the heart of a heated debate about cultural restitution, repatriation and the decolonisation of museums: according to Hicks, few artefacts embody this history of rapacious and extractive colonialism better than the Benin Bronzes – a collection of thousands of metal plaques and sculptures depicting the history of the Royal Court of the Obas of Benin City, Nigeria. Pillaged during a British naval attack in 1897, the loot was passed on to Queen Victoria, the British Museum and countless private collections.

However, beyond the white projections of blame onto Africans through the ideology of a punitive expedition and so much more, and beyond the case of Benin City, there is an urgent need for museums to work together to build a much larger body of knowledge and understanding around colonial looting and the development of global capitalism throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the earlier examples in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. “Rather than further hagiographies of Captain Cook, or balanced and passive histories of British looting of libraries, monasteries and palaces, or displays of pillaged objects where provenance is not mentioned, but the sharing of knowledge of museum collections as unique indexes of imperial theft in order to begin to build a new infrastructure to fulfil museums’ ethical responsibilities to dispossessed individuals, communities and nations – and also to visitors,” Hicks wrote in the conclusions of his work.

Some of the Benin bronzes stolen by the British from the Kingdom of Benin in 1897, on display at the British Museum. Photo credits: Lauren Fleishman

Making a powerful case for the urgent return of such objects, as part of a wider project of addressing the outstanding debt of colonialism, since the book’s first publication, museums across the Western world have begun to return their Bronzes to Nigeria, heralding a new era in the way we understand the collections of empires once taken for granted. Though, in this urgent, enduring ‘negative moment’, clear formal processes still need to be developed and evolved for the restitution of cultural remains by museums in the UK and globally: while human remains and the specific case of Holocaust spoliation are generally well covered by national policy and guidance, in fact, colonial spoliation remains a major gap.

It is therefore needed a new kind of typological work, based not on imagined types of object or culture, but on the different forms that acquisition through which colonial material culture came to Western museums and private collections has taken: in such a typology of taking, the first aspects to analyze – Hicks suggests – must be loot taken with violence; the trophies and spoils of ‘small wars’; those taken through the cooptation of élite classes; missionary and other confiscations of objects of religion and belief taken during colonialism; archaeological collections and tomb-raiding; scientific collecting of natural history specimens – as well as ethnographic collecting.

To this rich list, we would suggest adding the case of artifacts stolen in the midst of turmoil, which is the case of Lebanon, Syria, Libya, and many other countries in the region – in a way that ours will be the next case of looted goods returned to their homeland. To do so, however, requires a conscious and determined demand from civil society – impossible to imagine without a deep understanding of what the Middle Eastern cultural heritage once was, and now is no more.