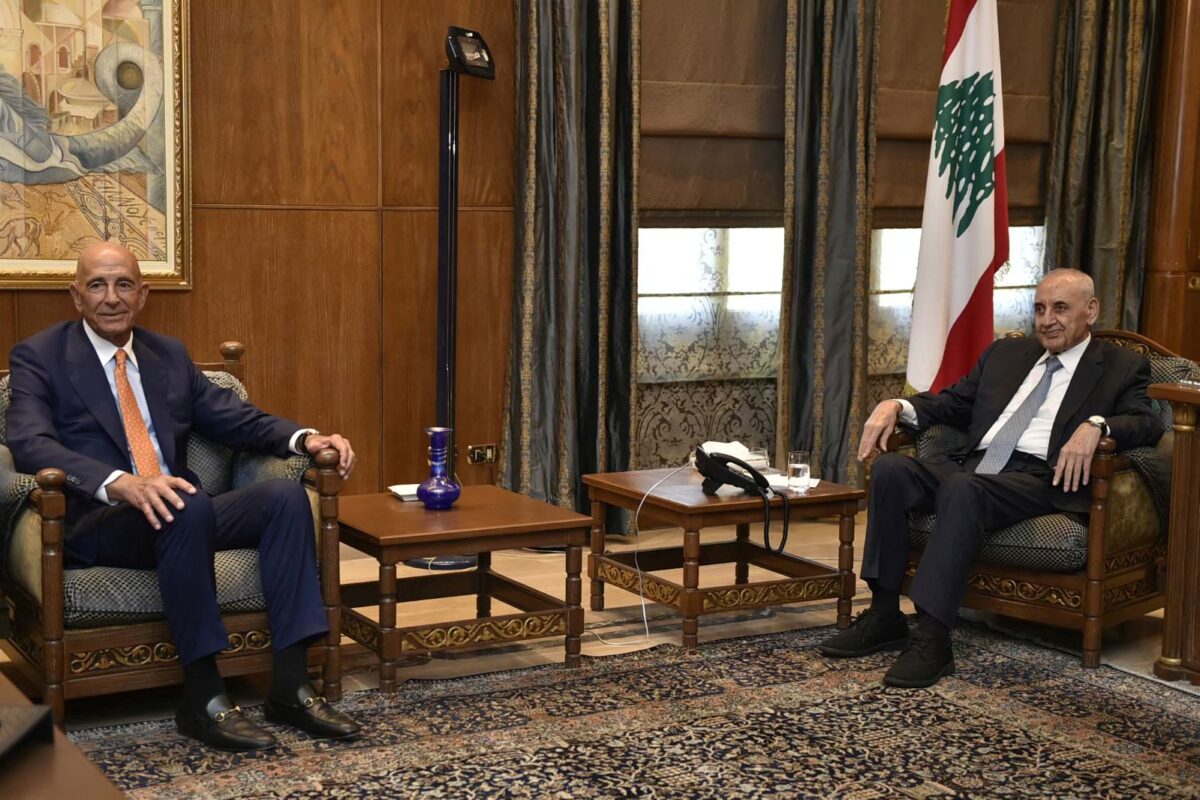

Tom Barrack’s visit to Lebanon this week was met with a mix of intrigue, confusion, and political overinterpretation. Some called it a warning. Others, a negotiation. And yet others dismissed it as vague American diplomacy.

But if we listen carefully, what Barrack offered wasn’t a threat, it was a bridge. A golden bridge, in the language of negotiation theory: a pathway that allows an opponent to retreat or transform without humiliation, without collapse, and without losing face.

This isn’t new. But the moment is.

A Door Not a Sword

Barrack didn’t speak in ultimatums. He didn’t lay down red lines. He praised Lebanon’s government for a “spectacular” response to the U.S. proposal on Hezbollah’s disarmament and southern border arrangements. That’s not standard diplomatic language. That’s signaling.

What he’s really saying is this: the United States has received Lebanon’s response and sees in it a serious and perhaps unprecedented willingness to engage the issue of state sovereignty. The government appears to be signaling that it is finally ready to confront the armed duality within its borders, a signal the U.S. is keen to support. What Barrack made clear, however, is that the days of armed pluralism — where a state coexists indefinitely with an independent, militarized political actor — are ending. Lebanon must choose whether it wants to reassert full statehood or continue in a model that no longer has regional or international tolerance.

Sovereignty, Not Resistance

One of Barrack’s most pointed remarks came in the form of a rhetorical question: “Do you think any other state would allow a political party with weapons to exist within it?” This was not a new frame being introduced, it was the reassertion of an existing one. For years, Lebanon has lived under the tension between “resistance” and “sovereignty,” with the line between state and militia increasingly blurred. What Barrack did was reaffirm that this ambiguity is no longer tenable. The international consensus — including the U.S., Europe, much of the Arab world, and many Lebanese themselves — has long held that a state must hold the monopoly over legitimate violence. What changed in Barrack’s visit is not the framing, but the sense of finality. The weapons question is no longer an open debate. It is now a closed file. The only thing left on the table is how the transition happens and whether it will be on Lebanon’s terms, or imposed by events.

What Hezbollah Is Being Offered

Contrary to the reactionary analysis of some, Barrack did not call for Hezbollah’s dismantlement or political marginalization. In fact, he was careful to signal that the U.S. is not interested in humiliation, but in resolution. His comment that Hezbollah must “see that there’s a future for them” is central to understanding the diplomatic strategy at play. This is not about erasure, it’s about evolution. Hezbollah is being offered the space to transition into a purely political actor, to claim its wartime legacy, and to rebrand itself within the state rather than outside it. This is the essence of the golden bridge: you help your opponent cross over to a new reality without framing it as defeat. You give them space to preserve their dignity, even as you dissolve the conditions that previously justified their armed status. That offer may not remain on the table forever, but for now, it represents a rare convergence between geopolitical pressure and diplomatic opportunity.

The Cost of Delay

Barrack’s tone may have been respectful, but his warning was unmistakable. When he said the region is moving “at Mach speed,” he wasn’t exaggerating. Across the Middle East, the landscape is shifting rapidly. Iran is recalibrating. The Gulf states have pivoted toward normalization and economic realignment. Syria is gradually reintegrating into the Arab fold. And Israel, for all its internal contradictions, is adjusting its regional posture. In that context, Lebanon’s current model — paralyzed by sectarian power-sharing, weakened by economic collapse, and fractured by parallel militaries — is increasingly unsustainable. Delay doesn’t mean stability. It means being left behind. The country is now at risk of falling out of step with both regional shifts and international support unless it acts decisively and owns its path forward.

The Real Question

This visit — and this moment — puts a clear question in front of Lebanon’s political class, and in front of Hezbollah: Do you want to help build a sovereign Lebanese state or do you want to hold it hostage until it collapses beneath you? That’s not a rhetorical flourish. It’s the defining political question of the post-war phase.

The bridge is open. But not for long.

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a Political Psychologist and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution at the Lebanese American University.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW