Despite obstacles, new secular groups formed or revived by protests look to run for elections against traditional sectarian factions

Nagham Abouzeid, 20, a third-year psychology student at the Lebanese American University (LAU), was convinced that she would lose.

She was running as an independent candidate for the student council elections and assumed that her chances of winning were close to none. Independent candidates had rarely been able to defeat the establishment parties in any student elections before. The Lebanese student factions affiliated with several of Lebanon’s ruling parties often ran brutal campaigns aimed at not only winning, but destroying their competition as well, she says.

Throughout her campaign, she faced constant attacks and harassment from her rivals. She recalls she was called immoral and “slut-shamed” because she was the president of the Gender and Sexuality Club in her university and her club distributed condoms during a university event.

“Their campaigns just started to get worse and worse,” Abouzeid recalled.

Her running mate Thomas Khoury would receive multiple calls every day, threatening him and cursing his family. A comment that he made about Lebanese President Michel Aoun when he was 12 was used to attack him. In addition to this, the parties created hundreds of fake social media accounts to comment on his posts.

After a long and grueling campaign, election day had arrived and Abouzeid was hoping they would get at least a few votes. Then the unthinkable happened.

She won.

“The results came out and I was in so much denial,” she recalled. “I was just staring at the [computer] screen.”

Abouzeid’s victory as an independent was not an isolated event. Independent wins in university elections became a trend in Lebanon last fall. For many young activists that led the anti-establishment protests starting October 17, 2019, this is a promising beginning.

New movements

Traditionally, Lebanon has been ruled by six major parties that have split up governmental seats according to their sects. The Christians have the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), Lebanese Forces (LF) and Kataeb, the Sunnis have the Future Movement, the Shiites have Hezbollah and the Amal Movement and the Druze have the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) as well as The Lebanese Democratic Party.

Since the beginning of the popular uprising on October 17, 2019, many activists decided to form groups so that they could better organize their efforts on the streets and hold information sessions where people could come and learn about the rights that they should be demanding as Lebanese citizens.

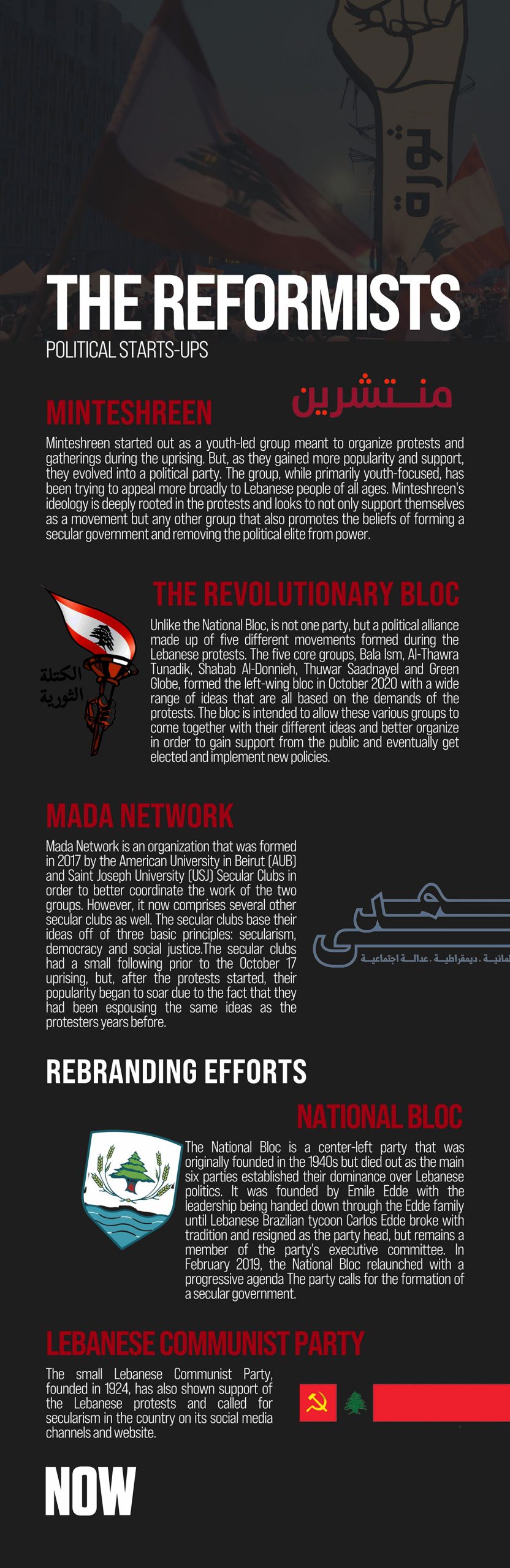

Over a year later, some of these groups, such as Mintishreen, Mada Network or the Revolutionary Bloc, plan to go further and try to present themselves as a viable alternative to the current political establishment. While the groups might vary in aspects of their ideology, they are working to unite themselves and the Lebanese people to oust what they call ‘the elite’.

Some older secular factions, such as the National Bloc, are also being revived as challengers to the political status quo.

The will to change

While all of these new parties believe in creating a secular political system in Lebanon and supporting the popular uprising, there are differences in the groups’ ideologies. They differ on tactics and what level of impact the uprising should have on the various movements.

Groups like Minteshreen have incorporated the demands of the protests into their core ideology. Others, like the National Bloc, see the movement as a mindset that should be used as a means of organizing a political movement that can build off of the momentum created by the protests.

“People and activists in the Thawra – it took time- but they noticed that the protesting in the streets has a ceiling. The proper way, if you want to change the regime, is a political party. More and more are understanding this and are more interested in joining or creating new political parties,” Pierre Issa, the 63-year-old general-secretary of the National Bloc explained to NOW.

When the Coronavirus pandemic put a stop to most protests in Lebanon, some of the activists decided to focus on organizing a political base.

“We did not say that the revolution has failed because we do not believe that,” Hussein el-Achi, a 32-year-old corporate lawyer and one of the founders of Minteshreen, told NOW.

“We think, on the contrary, that we have gained so much from the uprising. But we really reached the conclusion that, in order to really change this country, we need to be involved politically. We need to go and fight for municipal seats, parliamentary seats, university [student council] seats, syndicate seats and we need to organize ourselves.”

While the National Bloc acts as more of a traditional party in its attempts to gain support through suggesting new policies, others are taking a less traditional approach to their outreach.

The Revolutionary Bloc plans to educate the population on their civic rights.

The group often hosts workshops on a multitude of topics and holds them next to their respective ministries. For one event, they discussed the importance of an independent judiciary and held it next to the Ministry of Justice in Beirut.

“I think it’s important because people are asking questions now and they are demanding explanations from the elite. It may take a while, but we believe that we are on the right track because we can see [change in] the younger generation.” Guitta Msheik, a 24-year-old law student and representative member of the Revolutionary Bloc, told NOW.

However, despite differences, all groups agree that if they want to change the current system, then they need to be in it for the long run.

A sect-based electoral system and political clientelism

But the complicated Lebanese electoral system that favors the dominant sectarian factions is a primary obstacle for the new political movements to gain traction and win seats in the parliamentary. Since the end of the Lebanese civil war in 1990, the establishment political parties have quashed any attempts that independent movements have made to change the system or get elected to parliament by utilizing these electoral laws and making use of political clientelism, Fadia Kiwan, a political science professor at St. Joseph University in Beirut says.

The current election laws consist of voting districts divided into major and minor districts with the minor districts, for the most part, consisting of primarily one sect. For the major districts, voters are able to select one “list” of allied candidates for their area while the minor districts have voters choosing their preferred candidate. Candidates win if they gain a majority of the votes in their minor districts, allowing for parties to further utilize sectarianism as a means of securing votes.

According to Kiwan, if the law is not changed, the new parties stand little chance in winning a significant portion of seats despite seizing the momentum of the uprising to garner support.

Clientelism has also played a significant role in helping the political elite maintain power, Kiwan says. Providing money, jobs and other opportunities for people in their area, politicians create a system of dependency. If constituencies vote their “benefactors” out, then all benefits could disappear.

Parties, like the National Boc, disagree that the election laws need to be changed for them to be able to win seats in the parliament. Rather, they are calling for an independent organization to run the elections with plans to change the laws themselves after they are elected.

The National Bloc has been lobbying the international community to make holding independently organized elections part of the condition for any aid that would be given to Lebanon.

However, Kiwan believes that “they [the new parties] are wasting their time while talking about the tools” of how to hold elections since around half of the country continues to support the establishment parties.

“The electoral system, if it will remain the same, it will bring us back at least 50 percent of seats for the political elite,” she explained. “We have to change the electoral law at the earliest.”

One of the major changes that Kiwan proposes is holding two “tours” which would allow for representatives to be elected based on their ideas rather than just who they are or which party they are affiliated with.

“People will have a real opportunity to meet their candidates [during the first tour] and to discuss, to negotiate, to bargain, to impact their agenda and they may make their choice,” she stated. “On the second scale, it will be an election on a collective basis with lists. Here, politics will play its role. But we have more of a chance to see some revolutionary men and women being elected locally.”

While it seems unlikely that the current political establishment would be willing to change a system that is in their favor, Kiwan believes that it is possible to find a sort of middle ground by using any disunity between the major parties as a means of “infiltrating” and bargaining with all sides in order to create a fairer electoral system.

“So, you should be bargaining on the right and on the left to try to get something for you. We should invest in their division, but, at the same time, I think that the strategy should be infiltration much more than confrontation.”

Change through elections

Despite the issues with the election laws, the various groups and movements view their growing support as an opportunity to put independent candidates in the government during the parliamentary elections in 2022 and slowly start to oust the political establishment.

“I believe that if we have this anger, this drive for change that we saw on 17 October, even with this electoral law, we can change the status quo,” Aya Abou Saleh, a 20-year-old law student and member of the St. Joseph University Secular Club, told NOW. She believes that with persistence and time, a real opposition can be formed.

But not everyone is as optimistic. Sylvana Ayoub, a 20-year-old economics student at USJ who ran for student council on an independent list called Taleb, says that major gains will not be made until later elections because the current sectarian parties will not give up power without a fight. But she still hopes to see some success in 2022.

“I think that with the amount of support they’re gaining, they can at least have a few deputies in the parliament,” she said. There are legitimate fears that the traditional political parties will attack and intimidate the new blocs, often in the form of rumor-spreading and slander to delegitimize the movements. ”

But challengers say they are prepared for the confrontation. The National Bloc has all of their finances and funding made public on the party’s website in order to be as transparent as possible.

In order to counter these attacks, the Revolutionary Bloc plans on using social media and continuing to hold seminars so that they can make Lebanese society more aware of disinformation.

The National Bloc is planning on having representatives run in 2022 – the party is still in the process of choosing candidates. The plan is to run around 128 in total. These candidates could come from their own party or through coalitions that they form with others.

But not all groups are prepared to run candidates in the coming elections.

Revolutionary Bloc and Mintehsreen are looking towards the following one in 2026 so that they can better organize and gain further support. Meanwhile they say they will support any party that puts forward the same secular ideas.

“We will be very active in supporting all of the Thawra and opposition groups in the next elections,” Minteshreen’s el-Achi stated.

There is also the possibility that elections will be postponed to an unspecified date if the political and economic situation deteriorates too far.

It has happened several times in the past two decades.

A ray of hope: victory in student elections

Despite the odds stacked against them, the supporters of the revived secular parties and the new groups born in the protests are optimistic, citing the recent victories by independent candidates in the student council elections as proof that the Lebanese people are not only open to change, but demanding it as well.

The secular clubs in most Lebanese private universities have long fought for changes to the political system and have sought to do so through their university elections. However, prior to October 17, they were often dismissed as being unrealistic and too idealistic.

“Last year [in 2019], before the revolution, we only had two seats [in the faculty of law],” Abou Saleh recalled. “And no one would think that our ideals would ever get us anywhere. They were deemed utopian. But I think that we were in a state of collective numbness. Most people my age thought that this was how the country was made, that we cannot change the status quo.”

A year after the uprising, though, their ideas were now part of the mainstream in political thought in Lebanon and that translated to major wins during the 2020 university elections.

LAU was the first university that saw independent candidates win a sizable portion of the student council seats. Nagham Abouzeid was one of the biggest winners, taking home more votes than all three of her party-affiliated rivals combined.

Still a lot to overcome

However, the 2022 elections are still at least a year away and the support for a change of the political system could decrease in time.

In order to reach a wider audience, the new blocs are coordinating their efforts and plan on working together to gain support. Within each group are various committees of experts in their fields so that coordination is streamlined and allows them to better address any differences in opinions.

“Overall, everyone mostly agrees on certain big lines,” Revolutionary Bloc’s Msheik said. “That makes it easier for us to coordinate on the details. And since we have specialists and we are coordinating with mainly all of the groups of the revolution because we know them.”

Until the elections, both the National and Revolutionary Blocs representatives say they will continue to work on various projects. For the Revolutionary Bloc that means continuing to hold seminars and answering people’s questions in order to create a better-informed public.

According to the National Bloc’s Issa, it is only a matter of time before the ruling elite are removed from power. As more and more groups continue to become politically active, they will eventually be able to mount a serious opposition.

Many youth agree that there is a need for new, secular parties. After decades of corruption and political and economic mismanagement, they say they are hungry for change.

Ayoub, the 20-year-old economics student at USJ who ran for student council, says that people are starting to notice that they now have more options than the traditional parties and, coupled with the ideas coming from the new groups, this presents a unique opportunity for “the people to take back power” by electing representatives that are not part of the political establishment.

“They offer new visions, new plans, and different approaches than the ones we’ve been following for the past decades,” Ayoub explained.

“It makes me happy to see that my people are waking up, my people are becoming more and more independent, my people are spreading the word about these new blocs that are being formed because they’re happy to welcome change.”

Nicholas Frakes is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. He tweets @nicfrakesjourno.

Graphics by Tala Ramadan, head of social media at NOW. She tweets @TalaRamadan