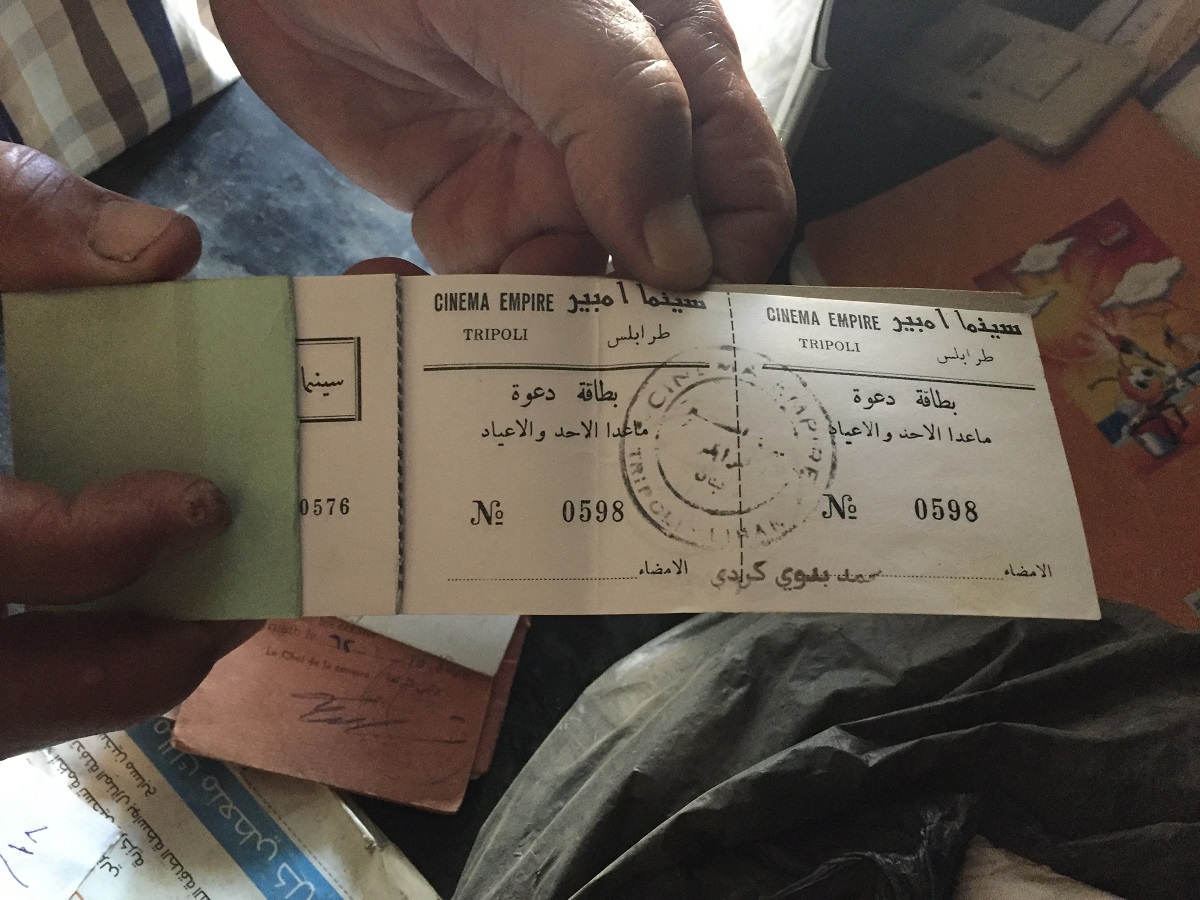

Aged film tickets coated in a golden hue, vintage signs, attendance records, hand-written and stamped business letters and envelopes, cash receipts and invoices from and to film distributors and an array of other documents unearthed from abandoned theaters helped Nathalie Rosa Bucher track down the history of Tripoli’s bygone cinemas and cinema culture. This cultural archive of a city often associated with extremism and labeled as uncivilized would unveil the once close-knit relationship between Tripolitans and cinema.

Formerly an independent journalist, Bucher had researched and published a story about the old cinemas in Tripoli with NOW Lebanon in 2013, a pursuit that would sow the seeds for a nine-year research into the city’s cinephilia, which appears to be frozen in time, culminating in an exhibition, “TripoliScope”.

Bucher landed a collaboration with UMAM Documentation and Research, a nonprofit cultural organization founded by Lokman Slim and Monika Borgmann, who were intrigued by the Franco-German researcher’s work and sent her to catalog every cinema that she knew still existed in the northern city, as well as those that had been demolished.

Often presented as a strident Hezbollah critic, Lokman Slim took on diverse roles in life as a thinker, writer, and publisher, and “ultimately rescued” Tripoli’s cinema archive.

“Many people associate him with being an outspoken critic of Hezbollah, but I find it also important that we tell this part of his story because it also shows that he cared about many things,” Rosa Bucher told NOW Lebanon. “UMAM’s work is about human rights; it’s about giving an emphasis to the importance of arts and culture.”

The power of the screen

It was a couple of years after she started her research that Bucher would stumble upon a ruptured door of one of the abandoned cinemas. She crawled through and found herself above a heap of dusty documents. Scattered across the hall, the records were those of Societe Commerciale Cinematographique Tripoli Liban (SCCTL) which managed nine cinemas in Tripoli during the last century’s worldwide golden cinema era.

The discovery was equivalent to finding the holy grail that would help Bucher piece the puzzle together.

“I cleaned the documents, organized them, and set up an exhibition in El-Mina Tripoli and the opening day was October 18, 2019,” Nathalie said giggling at the thought that time was not on her side. The day came after the October 17 Uprising broke out. She canceled the event.

A bit over two years later, TripoliScope was resuscitated and launched in December 2021 in Chekka, Hay El-Bahr, and remains open to the public until May 1st. The expo is taking place in the coastal city, around 18 km south of Tripoli, right by the blue water where the waves crawl gently to the shore. The venue was chosen merely because the space was available. There has been a steady stream of people visiting the exhibition from all over Lebanon, some even came more than once, Bucher says.

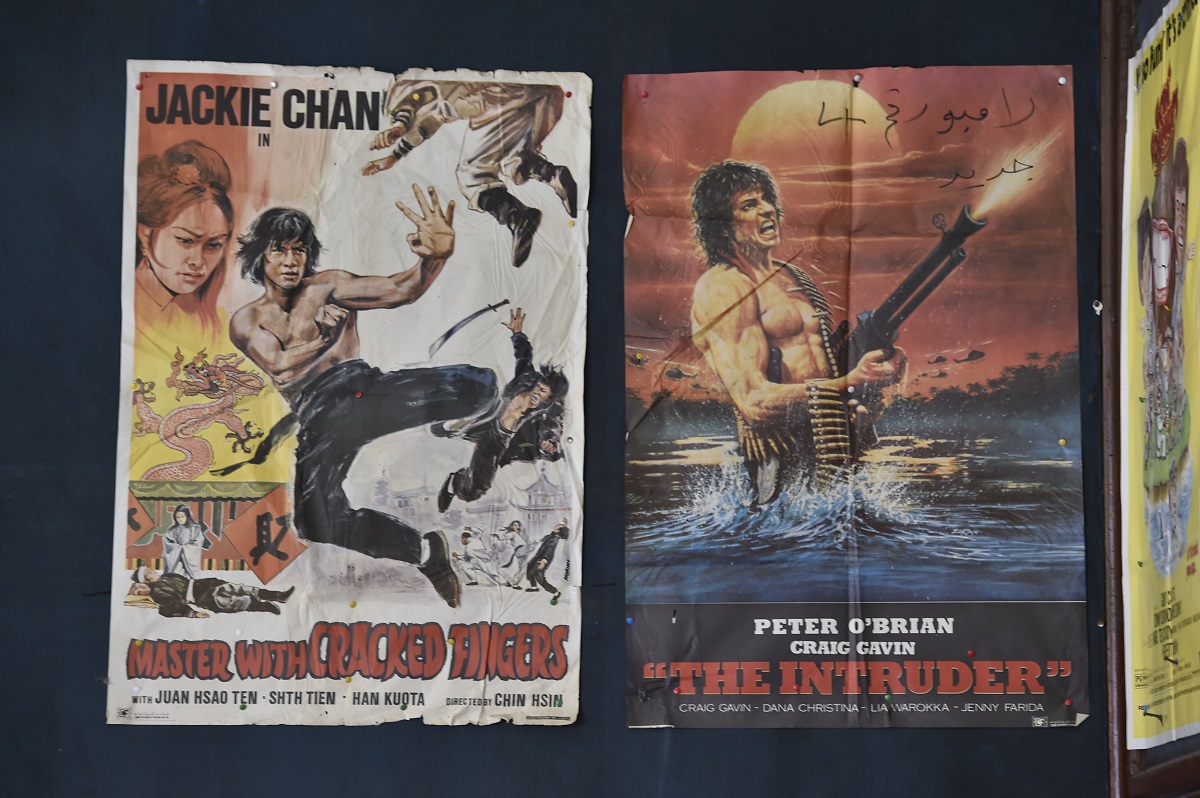

Divided into film screens, congruent with movie theater projection rooms, each section of the exhibition houses different materials the researcher found, namely SCCTL archives, film set photographs, and old images of Tripoli from the Arab Image Foundation, which is a partner in the exhibition. The materials provide pointers to the cinema-going culture between 1940 and 1970 and the films locals used to watch ranging from various genres and country origins such as Arabic, Hollywood, Italian, Indian, action, Cowboy movies, Spaghetti Western, Kung Fu, comedies, dramas, and even romance and erotica.

The different film selections and the lively discussions that followed forged the locals’ perspectives and impressions and contributed to the city’s vibrant customs and identity. Arabic and Indian movies were famous during Eid and other holidays, for instance, when movie theaters were brimming with those who wanted to celebrate.

Foreign film production studios such as 20th Century Fox and Columbia Pictures had distribution offices in Beirut and would deliver films across the country. Each film theater would screen different genres, so if one wished to watch an Egyptian movie, they would go to the Rivoli or Dunia. Cinema Hamra started as a regular cinema before becoming the most infamous of the cinemas screening blue movies.

“Each cinema had its identity,” Bucher said.

The social life of cinemas

Among the archive, the researcher and exhibition curator found screening permits alluding to the fact that every film had to go through the General Security censorship office before it was screened for the public.

In the exhibition’s “romance” section, where also old pornographic film trims cut with razor blades are displayed, one might relate it to and catch a glimpse of Giuseppe Tornatore’s 1988 Cinema Paradiso, where similar censorship takes place.

To skirt some of these restrictions, a man would imitate the sound of pigeons in the street in front of the cinemas’ to notify the locals that a blue movie is being screened.

Cinemas also operated according to social status. Some were premium theaters such as Cinema Palace, which accommodated around 1000 seats, followed by Colorado and Metropole with around 700 seats each. There was also a distinction between the “salon”, or the main grand hall, and the “balcon”, one or more raised seating platforms that curve around the sides of the auditorium, where mainly the upper-class were able to sit.

This is not an exercise of nostalgia nor is it to glorify that period because they were not necessarily perfect times. What I find important about this work is for people to know about it, I don’t want to be prescriptive about what they should make out of it afterward.

At least 41 cinemas existed in Tripoli’s metropolitan area and the port district of El-Mina, as well as in the encircling quarters that welcomed cinephiles, namely Metropole, Shahrazad, Capitole, Opera, Romance, Rio, Nejme, and El-Sharq.

One of the recovered papers reads, “The Opening of Colorado Cinema. Tripoli, Boulevard street. We welcome you at six, Friday evening January 14, 1955.”

Another piece of paper has registered attendance and screening times of the renowned Godfather film.

Bucher led a crowd through Tripoli’s quaint neighborhoods on a walk down memory lane on Saturday to explore the old cinema sites and venues, which are today either abandoned, demolished, or turned into a warehouse, falafel shop, gym, mattress and wood atelier and, ironically, DVD store. Some of the abandoned theaters, which, according to Nathalie, shelter vintage film projectors, are firmly locked, denying entry to those dying to catch a glimpse.

With mustiness in the air, broken glass doors, vintage movie posters still hung on retro wooden signboards, and somewhat distorted velvet stadium seatings, Colorado Cinema offered a window into the past for visitors who were allowed inside last week.

“Not an exercise of nostalgia”

A number of the workers who used to operate the old cinemas are still alive today and cater to the landmarks’ preservation. A former projectionist stands behind a falafel fryer. Nabil Sibai, who along with his father and brother once managed four cinemas, acquired the Rivoli Cinema’s 3D signage and repaired it after the cinema was torn down. It now hangs at his DVD storefront.

“There’s something very bittersweet about this; I think some people literally lived the cinema not just for one year but for decades of their lives,” Bucher said. “I think it did something to them when [the cinemas] were gone… Like hey, the show is over.”

“It was hard for them to process,” she continued.

Inside his modern-day DVD shop, which occupies the bygone Lido Cinema he once worked at, Mohammad Sibai reminisces about his favorite films and recalls, with great precision, American and Italian movie icons he looked up to like James Bond, Kirk Douglas, Sophia Loren, Burt Lancaster, Anthony Quinn, and Gina Lollobrigida.

“My father was 10 years old when he started working at the cinema and when I was born, in 1959, he had already owned a cinema where I would eventually work.”

Around 5000 people would flock to El-Tall square, and move between Cinema Palace to Colorado and all cinemas in between, at five in the afternoon, every day, to catch a film.

“On Sundays, you would be lucky to find a spot,” Sibai says. “Some people would also go from one cinema to another to watch different movies.”

Sibai speaks with appreciation describing what the cinema in his old days used to offer. He harks back to when the ladies used to fix up their hair, powder their faces, put on their finest dresses and go to the cinema when they wanted to go somewhere nice.

Besides generating profits from ticket purchases, there was another level of economy involved in the film industry, Bucher told NOW Lebanon. Among the archive, she recovered invoices from hardware and paint shops, sanitary and venue maintenance expenses, receipts from copper souks, municipal taxes, and telecommunication and electricity bills.

With the onset of the 1975-1990 civil war and with the advent of the Syrian Army, which enforced oppressive measures, cinema culture started to wane until it became prohibited when the Islamic Unity Movement known as Harakat Al-Tawhid arrived and operated in the north.

“It’s always important to be curious about what came before,” Bucher said. “This is not an exercise of nostalgia nor is it to glorify that period because they were not necessarily perfect times. What I find important about this work is for people to know about it, I don’t want to be prescriptive about what they should make out of it afterward.”

“But in this context where you have no national archive, no nationally driven effort to look at the past and deal with the past, it becomes very easy for anyone to put whatever story out,” she added.

Sally Abou AlJoud is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. She is on Twitter @JoudSally.

Photos of the Tripoliscope exhibit courtesy of Nathalie Rosa Bucher. UMAM D&R is on twitter @UMAM_DR. and Instagram @umam_dr.