Revolutions require enough people to force change to a political system.

We seem to have enough protestors and all the right reasons to revolt. But we do not have the appetite for forced change. And that may be for good reason.

This is not to condemn demonstrators demanding a sane government that delivers. On the contrary, the issues that plague our body-politic are robbing generations of normalcy. And the numbers are real – that a quarter of the population rose up in Beirut on March 14, 2005 against Syria’s occupation was astonishing…only to be outnumbered by nearly half the country demanding dignity and accountability in the days and weeks following October 17, 2019.

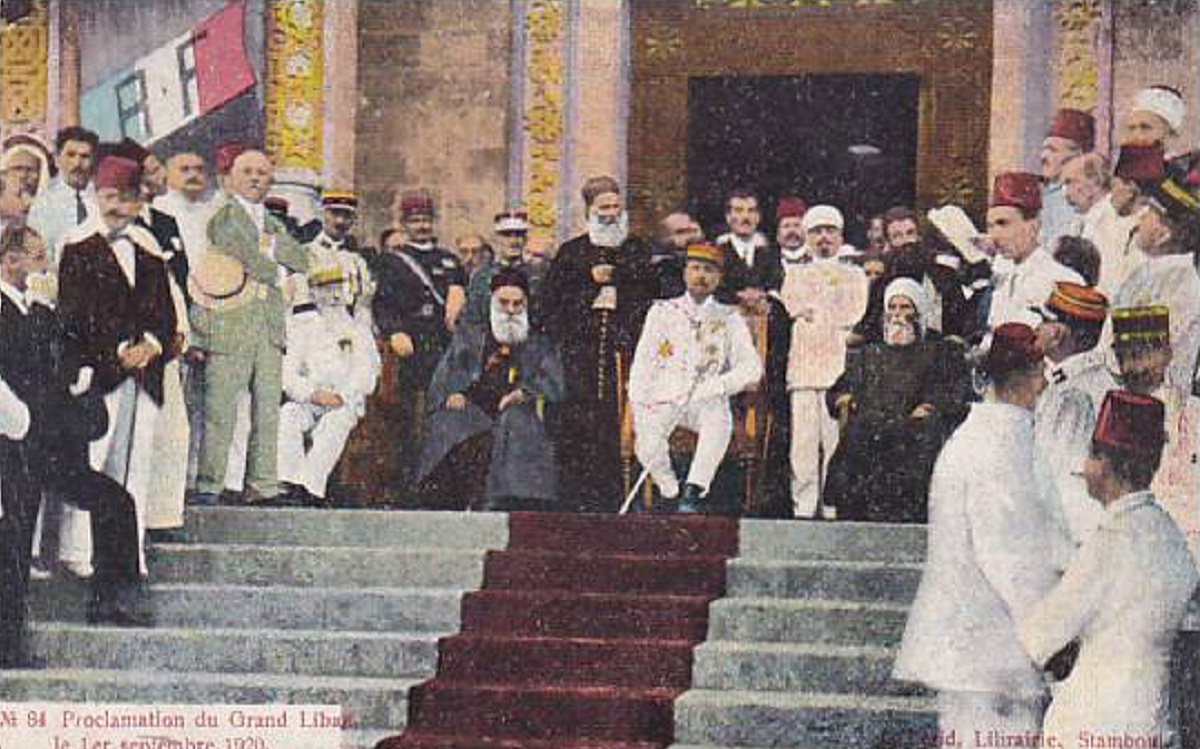

Dates and years aside, Lebanon has not had a successful revolution since its inception. The country as we draw it is fairly new, at least the unchanging borders that define it. But the strange and dysfunctional way of governing we hold onto predates Greater Lebanon’s recent centennial. And the political system appears to be here to stay.

Countries like ours take a very long time to come together. Independent Lebanon may be new, but the notion of Lebanon is old.

Placing us under Mandatory rule for just over two decades between two world wars sped up the formation process in an unsettling way, but it is a mistake to draw our current breakdown to a post-Ottoman French-led error. And it is equally misguided to argue that Lebanese are fed up with the system, itself. Our odd and perhaps outdated way of consensus-driven confessionalism allowed Lebanon to prosper with a multitude of communities and identities that defined real cosmopolitanism and tolerance. That it turned into a clunky and too often inefficient form of power-sharing is true.

What is false is that it brought us to war, followed by continued violence, economic misery and political paralysis. And regardless of whether it is fit for the 21st century, it will not change overnight.

It is not sectarianism

I beg to differ with a sizeable number of activists and members of burgeoning political parties (many I have marched with on the streets, consider friends and have interviewed on the podcast) on one key point: I do not think the core problem is sectarianism. I may sound 200 years old here and out of step with the times (even reality), but I say this as someone adamantly secular in my private and social life, and a Lebanese citizen without a sectarian – let alone religious – bone in me.

I think the word is pejorative for the wrong reasons, and it is a distraction. We no longer live in a functioning Lebanon that has the tools needed to chart its destiny. Instead, regional winds continue to navigate their misfortunes our way, and they make sectarianism seem more problematic than the accusation it accumulates.

“I do not think the core problem is sectarianism. I may sound 200 years old here and out of step with the times (even reality), but I say this as someone adamantly secular in my private and social life, and a Lebanese citizen without a sectarian – let alone religious – bone in me.”

Let me step away from sectarianism for a moment, only because a whimpering hooray happened late last week. The return of our weathervane, Najib Mikati, to the Grand Serail and the formation of a new government. Those brief gusts against Assad tumbled him in to replace Omar Karami in 2005. Six years later, Iranian lightning that struck March 14’s movement showered him back as Saad Hariri departed for (temporary) self-imposed exile. And this summer’s endless heatwave and humidity without gasoline or electricity – that is, until Syria gave its eternal blessing in return for a return to our affairs – brought tears to his eyes while re-entering our lives for a third round.

He is a compass for the wrong course and too often a spare tire. But he belongs to what is wrong with Lebanon, and that is not the country’s framework.

Back to sectarianism…

The current status quo is destroying the social fabric of our society. It mismanages our institutions and plunders our country’s assets in full sight. It is repugnant, untenable and forces many of us to flee.

But none of this is sectarianism. It is decades of every stumbling block that prevents what we desperately need – and that is reform.

Reform begins with implementing what the Taef Agreement laid out in 1989. It makes absolutely no sense that we still have no senate. Even under Syria’s watchful eye, Taef specifically called for its place alongside parliament. It was meant to mitigate the uglier side of sectarianism – insecurities that can lead to violence, undermining an already fragile state in a region prone to conflict – in a chamber among equals, and veto legislation when community representatives demand it. Sluggish, perhaps, but sensible, paving the way for a merit-based parliament that can ignore quota-based headaches and hurdles in favor of standard legislation.

Another wartime issue we ignored was the disarmament of all sub-state groups. Taef stipulated both the Syrian army’s withdrawal from Lebanon within two-three years (before they extended their stay) and legitimized Hezbollah’s armed presence until Israel’s eventual withdrawal. Generations of us adjusted to a particular abnormality – a perverted politics dressed with sectarianism that required militia weapons even after Israel let go of southern Lebanon in 2000, in order to liberate a largely uninhabited Shebaa Farms belonging to Syria’s occupied Golan Heights. A discourse determined by violence that presents our problems as existential and unresolvable.

Cajoling to that narrative is a mistake. Disarmament of all militias is a precursor towards reform, not an afterthought. Hezbollah inherently blocks – and when necessary, executes – any fundamental attempt at reforming the state. And they flipped the system’s power-sharing model on its head.

Hezbollah’s full inheritance in 2008 of what Syria’s soldiers and intelligence officers left behind was accomplished through outright violence. Not debate, democracy, referendum or even a new agreement (unless you reminisce over Doha’s forced national unity). Rather, a proxy-led takeover that turned its weapons against internal political opponents.

“Disarmament of all militias is a precursor towards reform, not an afterthought. Hezbollah inherently blocks – and when necessary, executes – any fundamental attempt at reforming the state. And they flipped the system’s power-sharing model on its head.”

No one voted for this disorder. And none of this was sectarian in nature.

I will concede that there is a bolder opposition in the making today. One that speaks loudly against Hezbollah’s hijacking of our security matters and foreign policy, and a coalition – however small in its current makeup – pursuing that platform in next year’s elections. Yet if they want lasting impact, they cannot ignore the last moment Lebanon was independent and governable. And the story of what happened in 1970 is too quickly shelved in favor of crisis management and stability – the most toxic of phrases in modern Lebanese history. Echoes of that misfortune are returning, describing Syrian influence’s rise as a needed counterweight to Iranian hegemony – not only among Assad’s local friends and nominal foes, but among European diplomats with a measure of American blessing.

Violent actors and their bad ideas thrive when a country loses its sovereignty. They perpetuate and exacerbate friction and division, and show us the worst traits of any society. Yes, Lebanon is confessional by design and consociationalism may be past its prime, but for a small state like ours in a difficult region that barely resembles itself, our political system withered storms in favor of weathervanes. And it ceased to function when its doors were forced open to problems fought over in our geography.

The catastrophe begins there. Agreements, protest movements, challenges against failed leadership, hundreds of thousands to millions of us yearning to move on…if Lebanon ever witnesses a revolution that lets go of sectarianism, it will happen after we reform what we were born with.

Overhauling that model while ignoring all that made it ungovernable will only add to Greater Lebanon’s downfall.

Ronnie Chatah hosts The Beirut Banyan podcast, a series of storytelling episodes and long-form conversations that reflect on all that is modern Lebanese history. He also leads the WalkBeirut tour, a four-hour narration of Beirut’s rich and troubled past. He is on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter @thebeirutbanyan.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOW.