There is no reason to have any faith in local investigations pursuing political crimes in Lebanon.

The reason is simple: Hezbollah.

Yes, there are many repugnant individuals that represent Lebanon’s lethargic, corrupt, too often thuggish political class. Many of them were better at running civil war fiefdoms than national aspirations or good governance. Their mediocrity bears no reflection on our society or our sectarianism. Enough with the self-flagellation and blaming our confessionalism for our flaws.

We cannot get rid of these torturous leaders because of the real threat of violence. The defenders of the violent realm we live in – a militia that intimidates its foes with personal threats delivered to pressure, assassinates those that do not pander to their ‘politics’, subjugates whatever is left of the Lebanese state to its security interests that preserve the Syrian regime and Iran’s military leverage, and defiantly portrays any serious inquiry into why more than 2,700 tonnes of ammonium nitrate were parked in Beirut’s port as an American conspiracy serving a Zionist agenda – will never surrender.

They will not yield either to local judges cautiously questioning the outer realm of the regime or to a population increasingly aware that this group has taken Lebanon to hell.

And within that population, many citizens, including myself, have waited for years for one small step in the right direction.

Allow me to make things personal. The 27th of every month is a date that haunts me. I have woken up to 94 of these reminders since my father was murdered on December 27, 2013. The suspension of the port blast investigation followed by the dismissal case against Tarek Bitar landed on the 27th, making a personal wound open up more than usual. But this country is a landmine of markers of murder, and somehow brought a private exchange full circle.

In the days after the car bombing that took my father’s life in front of Starco in downtown Beirut at 9:40am, I made multiple visits. I sat with the current (then) prime minister in his Ottoman history-woven office at the Grand Serail. He assured me that the killers would be found within a week. And his confidence was hilarious. I told him I knew that he knew that would not happen. He told me my emotions were right, my skepticism was well-earned, and I had every reason to doubt his intentions. But if I gave him just one week, he would deliver with answers. I markedly asked him if that also meant Hezbollah. He repeated: “One week.”

They will not yield, either to local judges cautiously questioning the outer realm of the regime or to a population increasingly aware that this group has taken Lebanon to hell.

Ninety-some weeks later, no answers.

I made my way to Baabda to speak to a previous army commander on his way out. The then-president produced through forced national unity offered no promises. We turned to the windows from his palatial office looking towards the greenery long depleted from Beirut (and most of Baabda). I asked him why he was unable to point the finger at those he knew were responsible. He gave no answer, and instead replied with kind words and memories of working with my father. I pressed him that if he respected the Baabda Declaration he presided over, which my father helped bring to life – even if Hezbollah signed and ignored it – he would have the courage to speak truth to ill-gained power.

He sat in silence.

I continued my personal (and knowingly limited) crusade in search of anyone with authority willing to condemn the hitmen who burned my father’s body to charcoal black, injured and killed multiple passersby commuting through downtown and robbed Lebanon of a proud patriot diplomatically determined to end this country’s geopolitical nightmare.

I had a short call with the then-self-exiled-yet-to-return eventual caretaker-turned-resigned-former-prime minister. He was, for years, my father’s employer. It was straight to the point: he would not sleep until those killers were brought to justice.

When the three-time-former prime minister returned for his fourth round, I insisted on meeting him. I had met him twice before, briefly, both in Washington, DC. The first in 2005, in the months following his own father’s assassination. I went to pay my condolences and wish him success – that encounter may have lasted a minute. Again, ten years later, for less than a minute, I crossed paths with him in a hotel lobby shortly after his arrival. Good to his word, he was sleep-deprived. He did not speak – I simply said hello with well wishes.

That third encounter was at a restaurant downtown in early 2017, not far from Starco. I was invited to lunch with a number of his advisors and the then-minister of interior. The same man who submitted the most recent dismissal case against Bitar.

The conversation was limited. Local (and in my mind, shallow) politics were being discussed at the table, and I looked for a minute to ask the then-prime minister why there was no progress into my father’s assassination. I managed to squeeze in one question: “Do you have any information about his killers?” He replied: “We know who did it, and when they come out of hiding, we will arrest them.” I suppose in retrospect I knew he would have nothing else to say. Why would his answer be any different than any figure who has served under Hezbollah’s state capture? He had already compromised March 14’s principles to the point that he was the militia’s preferred prime minister. I told him I did not believe him, and that was the last time I saw him.

And within that population, many citizens, including myself, have waited for years for one small step in the right direction.

Just over two years later, long having abandoned any expectation from local trial or sincere effort into ending impunity, by complete chance, I was sitting near the then-turned-former minister of interior. In downtown once again, at a hotel bar, with entirely different company and sharing alternate universe conversations.

I saw him get up to leave. The flood of memories of everything that went wrong after December 27, 2013 hit me. I wanted, once more, to press him with the same question. I managed to get to the exit before his entourage arrived, and as they were about to usher me away, I used my family name, insisting on having a word. The former minister recognized me and instructed his security to let me approach.

“You were Minister of Interior for over four years. I know you had little appetite for my father’s politics, and I know he had none for yours. But beyond making this personal, this is a matter of principle. You never lifted a finger into investigating who killed him. There was no interrogation, no arrest and absolutely no justice for his loved ones. Had there been any effort made, I would have saluted you proudly and publicly. But I know without you saying it: there was no investigation.”

Unlike the others, his response was somewhat honest: “It was a political decision not to pursue those answers. The situation in this country does not work in favor of men like your father. And regardless, it was beyond my control.”

In the end, those questions are best asked directly to Hezbollah. But in a country where fingers point at them, investigations die with the victims.

Honest to a point. After filing the case of dismissal against a far more modest and honest judge on September 27, he seems to be in control.

In control of making sure that investigations that approach Hezbollah run dry. Joining others in protecting the militia in return for their own political survivability. Politics perverted by proxy, nominal opponents spared for turning their blind eye and the mafia and militia becoming one. Bitar began to press for answers, only to make a direct threat against him known before having his investigation suspended.

In the end, those questions are best asked directly to Hezbollah. But in a country where fingers point at them, investigations die with the victims.

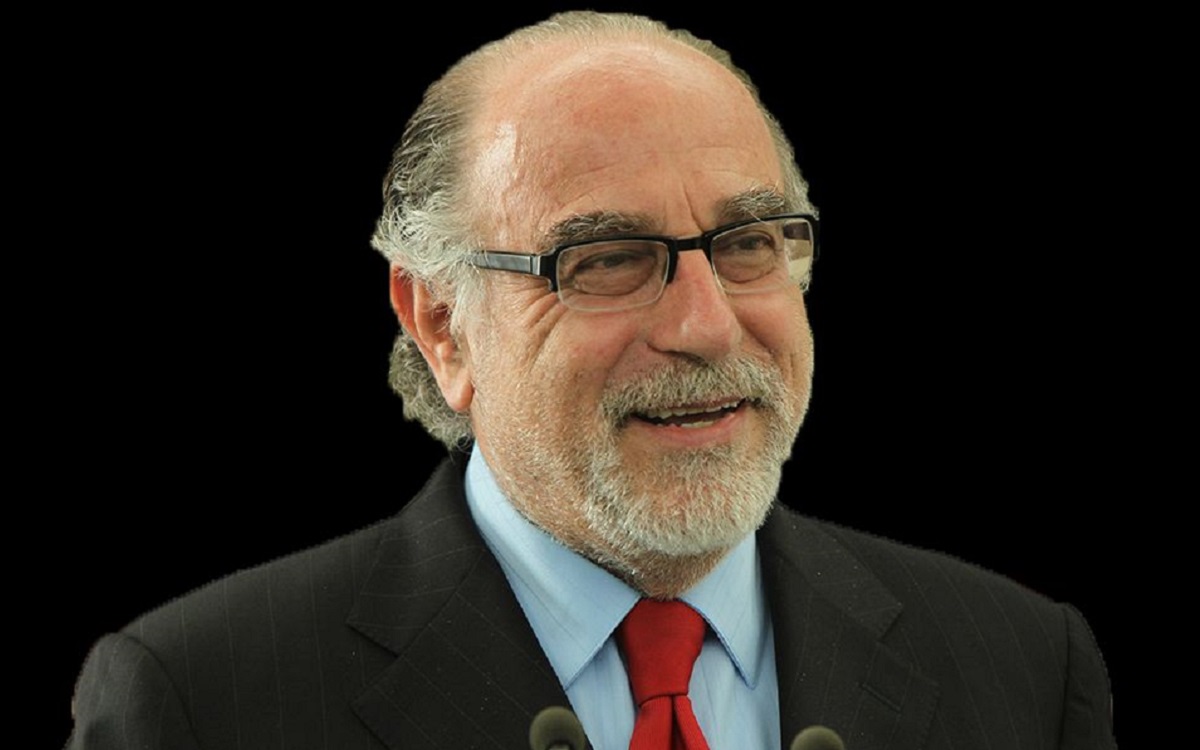

Ronnie Chatah hosts The Beirut Banyan podcast, a series of storytelling episodes and long-form conversations that reflect on all that is modern Lebanese history. He also leads the WalkBeirut tour, a four-hour narration of Beirut’s rich and troubled past. He is on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter @thebeirutbanyan.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOW.