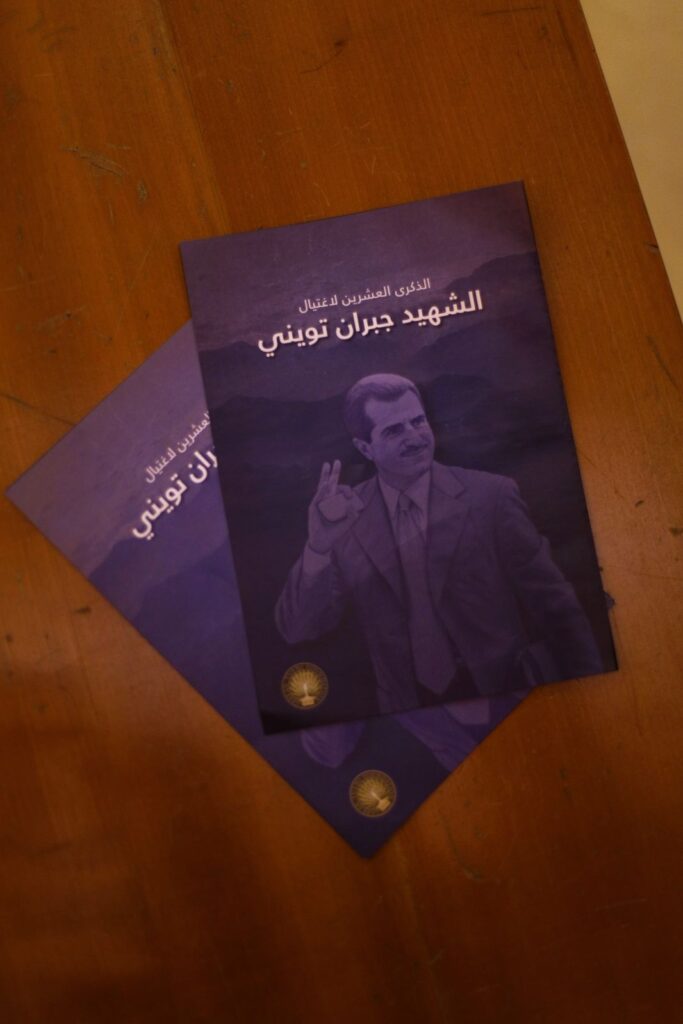

Twenty years after the assassination of journalist and parliamentarian Gebran Tueni, Syria celebrates a year without the Assad regime — the very political force Tueni criticized for its occupation of Lebanon.

Tueni, editor of An-Nahar and a prominent politician, was killed in 2005 for criticizing Syria’s military and political influence in Lebanon. His assassination was part of a broader wave of targeted killings against journalists and politicians. Among the victims are high-ranking leaders like the prime minister at the time, Rafic Hariri, and Samir Kassir, a journalist who, like Tueni, opposed Syrian interference in Lebanon.

Photo By Anthony Daaboul

Tueni was killed by a car bomb “because he dared to address hard truths to the Syrian leaders who controlled Lebanon, oppressing the country and making decisions on behalf of the Lebanese people,” journalist May Chidiac, a survivor of the 2005 assassinations, told NOW Lebanon. Chidiac herself lost an arm and a leg in an assassination attempt that year.

A year ago, decades of Assad’s rule came to an abrupt end when HTS leader Ahmed al-Sharaa ousted Bashar al-Assad, ending fifty years of Baathist control in Syria. On Monday, Syrians across the country celebrated the first anniversary of this historic transition.

“Now finally [Gebran] got his revenge,” Chidiac said regarding the dismantled Assad regime, which Tueni fought against and paid with his life. “I think while he is watching us from up there, he is happy, thinking that all his sacrifices were not in vain,” she added.

Tueni had strongly criticized the Syrian occupation that began during Lebanon’s civil war in the late 1970s and persisted for nearly three decades. Syrian influence extended deep into Lebanese territory, domestic politics, and the security apparatus. “Not many had the courage to look their future killers in the eye, so honestly and clearly, and tell them the truth as Tueni did,” Ayman Mhanna, executive director of the Samir Kassir Foundation told NOW.

Photo By Anthony Daaboul

Since the fall of the Assad regime, the political situation in Lebanon has improved. “The country is definitely better off without that Syrian regime,” Mhanna said. Syrian supply lines to the militia Hezbollah have been severely disrupted, and the weakening of the group has made Lebanon slightly safer, he argues.

But accountability and sovereignty remain problematic in Lebanon. The country ranks 132nd out of 180 countries in this year’s newly released World Press Freedom Index, reflecting ongoing challenges such as political control of mainstream media, harassment of journalists, and widespread impunity for attacks against them. Beyond physical threats, there is a new threat: misusing defamation laws and Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation (SLAPPs) to intimidate journalists, Mhanna says.

“Killers roam free. We need to end it.”

Accountability for political assassinations has been virtually nonexistent. “It is shocking that in the entire history of journalist assassinations in Lebanon, only the killer of Kamel Mrowa was ever arrested and tried — and when the civil war broke out, he was basically freed from prison and escaped,” Mhanna emphasized.

While the International Tribunal for Lebanon investigated the assassination of Hariri and sentenced three people with life sentences in absentia, they were never arrested or imprisoned by the Lebanese authorities.

The Lebanese justice system has normalized political violence, allowing killers to operate without fear of consequences while silencing victims. “We must end the culture of impunity that has killed so many journalists and political leaders over decades,” making accountability the norm rather than the exception, Mhanna argues. “Killers roam free. We need to end it.”

Photo By Anthony Daaboul

Political intimidation also undermines elections, particularly in areas under the influence of armed groups. Chidiac noted that in Shia-majority regions, Hezbollah members “were threatening candidates, burning their houses, and forbidding them from presenting themselves” to keep their grip over parliamentary representation.

“You can say whatever you want, but they can still do whatever they want to you,” Chidiac explained. For example, she has criticized the slow disarmament of Hezbollah in the North of the Litani River and the Beqaa Valley. Then, “I was targeted with 500 grams of explosives placed under the seat of my car. The danger is still there.”

Ending impunity would improve the safety of journalists and politicians, while increasing the space for debate and for new political figures — including Shia politicians opposing Hezbollah, Chidiac argues.

Photo By Anthony Daaboul

As Lebanon marks two decades since the loss of Tueni, his legacy serves as a reminder of the value of journalism beyond sectarian boundaries and the ongoing problems in Lebanon’s justice system.

Laura is a German journalist. She has previously worked in Brussels and Berlin for POLITICO Europe.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW