Nine years after the You Stink movement started, triggered by the closure of Beirut’s main landfill and trash piling up in the streets of the capital, very little has changed. On the politics behind waste management, the risks of Lebanon’s garbage crisis, and the activists’ wearing attempts towards environmental justice

Returned to walk the streets of Beirut, two months after having been away, the smell of garbage is what strikes my senses the most. Smell – as I stand next to an overflowing dumpster in the center of the city – suffers more than my hearing at the roar of a sonic boom, more than my sight when faced with entire fields burned by fire, yet another uninhabited building, darker streets while days get shorter. Nine years ago, in this same period, the end of August, the average temperature was 29 degrees – three less than today – and 20,000 tons of garbage were piling up in the streets, flooding across neighborhoods, triggered by the closure of the Naameh landfill – an abandoned quarry situated in the Chouf district, 16 kilometers south of the capital, that by the time had accumulated around 12 million tons of waste: four times more than its expected capacity.

A stench similar to that of these days, in the summer of 2015, sparked protests against poor trash collection and management, culminating in the ‘You Stink’ movement – a name that pointed to both the smell of uncollected trash festering in August’s heat, and to the perceived corruption underlying the Lebanese government. The movement grew to such a size that it threatened the political stability of the country: but while the trash was eventually removed from the streets to placate citizens, the response to the protests caused worse damage than their triggering genesis.

Garbage piled up in the streets of Beirut, August 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

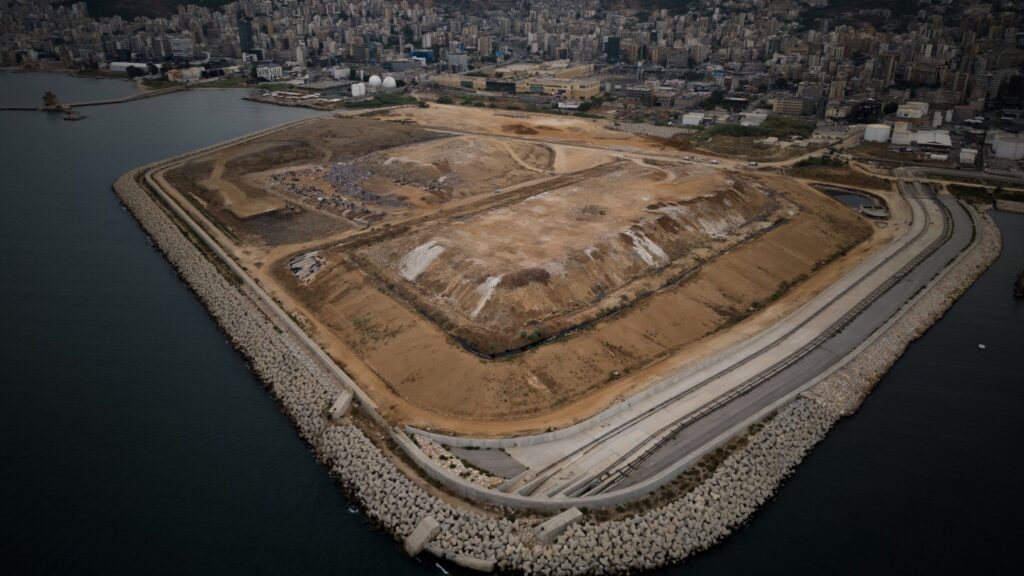

Lebanon’s fraught relationship with waste disposal is well known, as the country has faced recurring waste management crises due to inadequate systems, economic challenges and political corruption. After the Naameh landfill hit its capacity, the government reclaimed over 280,000 square meters, equivalent to more than 39 football fields, along the waterfront of Beirut to establish the country’s largest and newest waste disposal site. Piling rubbish on the coast of one of the eastern Mediterranean’s most popular seafronts, it commissioned two private companies to build three new coastal landfills in 2016: one in Bourj Hammoud, one nearby in Jdeideh, and one in the southern suburb of Costa Brava, next to the airport.

At the time, activists and journalists voiced concerns about the landfills, built on reclaimed land on the sea: seen from above, they look like islands of poisoning plastic and organic waste. Their toxicity, though, was never assessed, and waste was buried in the sea months before the breakwater barrier was completed in 2017. Nowadays, the three landfills still receive waste from the capital and about 250 municipalities in the region. With a few exceptions, in fact, the rest of the country has no proper landfills, just hundreds of illegal dumps: as no municipality wants to bring down the price of its real estate, dumps end up on poor coastal regions, whether in Beirut or in Sunni-majority areas of Saida and Tripoli. So that garbage too, in Lebanon, ends up being a socio-sectarian issue.

A garbage collector oversees a clean-up of one of north Beirut’s trash-infested beaches, January 2018. Photo credits: Tamara Qiblawi. Source: CNN

Brief history of Lebanon’s waste management

The 2016 fix – after the closure of the Naameh landfill – was just another of Lebanon’s short-term emergency measures, the latest in a string of emergency plans adopted after the end of the civil war in 1990, wrote Human Rights Watch in 2017. Lebanon’s garbage crisis, in fact, didn’t really start in 2015: that was just the year it reached Beirut and Mount Lebanon, the wealthier parts of the country.

The country has never had a comprehensive waste management system that covers its entire territory. Before the outbreak of the Civil War in 1975, the municipalities were in charge of the garbage collection: it was their responsibility to treat and collect waste. War, though, didn’t only mark the starting point of modern armed conflict, the deterioration of the state and the coalescence of militias in providing security – but it defined the modernization of its waste collection industry.

Before it broke out, most of Beirut’s waste was dumped in Qarantina, a run-down neighborhood near the city’s port. That, though, stopped in January 1976 – after a massacre conducted by right-wing Christian militias, the Phalangists, killed 1,500 of its majority Muslim inhabitants. It was only two years later, in 1978, that the capital’s municipality decided to dump most of its garbage into the sea. East Beirut’s rubbish went to Bourj Hammoud, with the small coastal dump, locally known as Normandy, growing exponentially over the following decades, covering the Armenian neighborhoods’ sandy beaches and standing more than 40 meters high by the mid-1990s. With half of its volume submerged under the sea level, the dump reached, in 1994, five million cubic meters. The refuse was mixed with sand and war-time rubble from Downtown to create the foundation of what was supposed to become the capital’s finance center: from war waste to dead bodies, every kind of scoria was thrown into the sea, causing a fatal, inevitable environmental disaster. Because of gas and ammunition being submerged as well, explosions were usually felt underneath the ground.

In a report entitled ‘The toxic ships’ and published in 1996, environmental NGO Greenpeace denounced that in 1987 the Lebanese Forces – controlling the port at the time – dumped thousands of barrels of smuggled toxic waste from Italy in the Normandy dump in exchange for thousands of dollars. When the Czechoslovakian ship Radhost docked at the port of Beirut with the first of several shipments from Europe – 15,820 barrels of industrial toxic waste from Italian cleaning firm Ecolife, which had contracted the waste management company Jelly Wax to transport and dispose of the waste – the 2,400-ton shipment contained a toxic cocktail of chemical compounds: flammable substances like methyl acrylate, ethyl acrylate, pesticides, heavy metal cyanides, and toxic nuclear waste.

The rubbish was covered with a layer of soil for temporary protection but remained untreated, according to a 2009 report commissioned by the local municipality – with obnoxious smells’ ongoing production and its leachate infiltrating the sea destroying sea life within a radius of hundreds of meters. The practice of waste exportation was banned once Lebanon became signatory to the Basel Convention on the Control of Trans-Boundary Movements of Wastes and their Disposal (1989), an international treaty designed to reduce the movement of toxic waste from developed countries to less developed nations. But still today, there is no knowledge of what waste actually lies buried in the dump site. The neighborhood of Bourj Hammoud was clearly not deemed attractive enough for high-end real estate plans: when the war finished, part of the waste treatment process underwent privatization, but plans to recycle the waste were implemented to only a very modest extent. The dump remained open until local protests forced authorities to close it in 1997.

After the closure of Bourj Hammoud’s Normandy dump, the waste from Beirut and its suburbs was sent to a newly opened landfill inland near the southern city of Naameh – the one that triggered the You Stink movement: as there was no alternative waste disposal plan, refuse sat, uncollected, for weeks in the sweltering heat in the streets of the capital, creating the 2015 rubbish crisis. The newly-opened landfills in Bourj Hammoud, Jdeideh and Costa Brava, way bigger than the Normandy dump – created without the pretext of a civil war, the difficulty of movement of a civil war, the lack of control of a civil war – unmask yet another sad face of Lebanon’s ungovernability: that of a corrupt system, playing at solving the manifold issue of waste management with its mere transportation. From one landfill, to a larger, more toxic, less manageable, other.

Bourj Hammoud’s main landfill, September 2023. Source: The New Arab

Sewage flows into the sea at Costa Brava, July 2017. Photo credits: Constanze Flamme. Source: Zenith

A dysfunctional system buckling

For decades, Lebanon’s waste management system has been highly centralized. In the areas of Beirut and Mount Lebanon, the government has been awarding contracts for waste collection, street cleaning and landfill management to firms that are typically affiliated with political élites – albeit critics have blasted the system for being expensive, opaque and poorly regulated.

To give an example, in October 2021 those claims were thrust into the spotlight after the United States sanctioned two Lebanese businessmen who had waste management contracts, claiming they profited from “pervasive corruption and cronyism,” for a total of 430 million dollars. In its statement, the US Treasury claimed a company owned by one of the blacklisted men, Jihad al-Arab, had reportedly added water to rubbish containers so they could bill the state more; while a firm owned by the other sanctioned man, Dany Khoury, had won a contract to operate a landfill, only to be accused of dumping toxic waste and refuse into the Mediterranean Sea.

Beyond corruption, however, the current system also fails to address roughly half of the waste the country produces: and without treating it. In fact, while the central government contracted the companies Sukleen and Sukomi first, and then RAMCO and CityBlu, to manage solid waste for most of Beirut and Mount Lebanon under a 1997 emergency plan – whose waste treatment’s rules had not been respected -, municipalities in the rest of the country have been left largely to their own devices, without the resources or expertise to adequately manage their waste. As a result, apparent across the country’s poorly funded municipalities, unsorted waste is routinely sent to some 900 open-air dumps to be burned, creating a public health hazard. And garbage’s burning is not just a nuisance: it triggers Lebanon’s obligations under international law.

At this point, it is clear that the solution can’t be the opening of yet another landfill. Every time a new landfill opens, in fact, and the government gets funding from international support, mainly embassies, it fails to obey the given rules about waste treatment. Also the one in Bourj Hammoud, opened in 2016 as a response to the closure of Naamieh and the You Stink protests, was supposed to act under the rule of law. Today, every morning, dozens of Syrian workers – mainly children – get up at dawn to collect recyclable garbage to sell to illegal waste-management centers, mainly located in the eastern district of Nabaa, accepting to irremediably compromise their health for very scarce livelihoods. And washing themselves in awfully polluted waters.

A fisherman on the corniche of Beirut, in front of waste floating in the sea, July 2017. Photo credits: Constanze Flamme. Source: Zenith

Running against time

At the same time, environmental activists warn that if Beirut’s main landfills close – meaning waste management in Lebanon becoming decentralized, without a well-structured plan – the country will be facing an unprecedented tragedy. “And not even a normal one,” presaged Carlos Ayvazian, social entrepreneur, founder of Wasted Treasures, and currently working with Green Mount Recycling. As if, in Lebanon, the scale of tragicity was measured in degrees of normality. “If each of the 250 municipalities that are currently relying on the government’s system for Beirut and Mount Lebanon – unequipped and inexperienced on how to handle waste – start to manage theirs, we will witness a horrible scenario. Way worse than that of 2015.” So it is better if they remain open – I wondered. “It is not a matter of what is better,” Carlos replied. “It is just that we have no other choice.”

In the eventuality that the main landfills close, as it has recently been discussed by the government, and local actors start managing their own waste, they would likely collect garbage at the end of each village, between their municipality and the adjacent one, storing it until it becomes too much to handle. Then, they would probably find a nearby forest, a big hole – or dig one – and use it as a dump, growing bigger and bigger, until it will reach a size they won’t be able, again, to handle. So they’ll light it up and pollute not only the environment, but their own people, in a way that would have no end. “It is not just about the carbon emissions that would be spreaded in the air: it’s about what we will force ourselves, our families, our children, to inhale.”

And even if the companies finally start to treat the waste – as per international law – there is no solution for the waste which is already there. In Lebanon, it is already too late to improve the state of things: now, it is only a matter of preventing the damage from becoming fatal. Collectively, indiscriminately fatal.

According to Carlos’ experience, actively working in the field since 2021, and with Green Mount Recycling (GMC) since last year, the reason why waste management system in Lebanon is so weak, is that people don’t work on it from the beginning of what they call the ‘decentralized waste management value chain’: a sequence of actions – from awareness, to collection, to secondary sorting, to recycling, to eventually manufacturing – that today seems the only way for Lebanon to cope with its ongoing and worsening garbage crisis.

“If people don’t sort at their houses, at least the organic from the non-organic, the value chain of waste management can’t be completed, and the whole process fails – regardless of what you do later. It’s too expensive to treat waste after it is put together. First of all, if you put organic waste with plastic, paper or cartoon, the recyclable waste is not recyclable anymore: even if you try, it is too dirty to be valuable. You would need to clean it before recycling, and we’re speaking about millions of tons of water every day, it’s unimaginable,” Carlos explained.

With the help of US AID under the DAWEER (Diverting Waste by Encouraging Reuse and Recycling) project, GMR collects every day three to four tons of recyclable waste from 16 municipalities around Ras el-Matn, in the district of Baabda, picking up door-to-door – for free and regardless if it is profitable for them – while providing cages across the villages where to drop waste. Moreover, a newly-founded application – Yalla Return – allows recyclers to incentivize, monetizing the effort of sorting waste into exchangeable rewards, cash, or funds to donate.

To give an idea of the impact of their actions, every month, a recycling report provides figures of landfill space saved – 3,057 m³ only in August 2023 -, equivalent in large bins – 4,632, in the same period -, medium-sized trees spared – 3,328 – and plastic bottles diverted – 1,181,466. A form of action that goes beyond merely rhetoric activism; immersed in the territory involved; rooted in it through the encouragement of the local communities, trained through capacity building, resources and tools, as well as promotional materials, so that they can go with the company to knock on their neighbors’ doors, warning them about the risks of what’s currently happening: that if we don’t start now, if we don’t put the effort to run against time, together, garbage crisis is going to be one of the worst tragedy Lebanon has witnessed, beyond the self-proclaimed boundaries of normality.