Girls and boys of different faiths, both Syrian and Lebanese, gathered in the mountains of Akkar for R&R’s ninth summer camp: beyond discrimination, they’re building the basis of a reconciled future for the generation of tomorrow

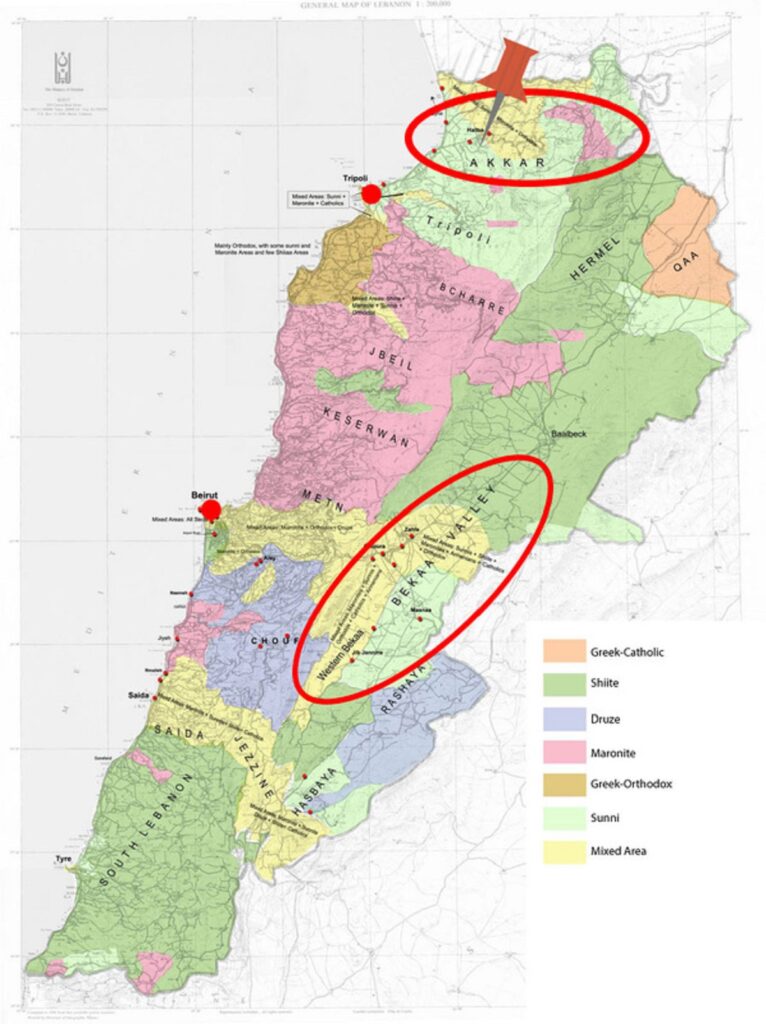

Above the mountains of Michmich, Akkar, not far from the Syrian border, the silence of the hermitage is broken by a high-pitched, shrill and sing-song roar: it is the play cry of two hundred and fifty children, Maronite, Orthodox, Sunni and Alawite, all between 11 and 15 years of age. They come mainly from Syria – Idlib, Homs, Aleppo, Hama, Latakia – and from the villages of the region that hosts them, the poorest in the country. And which, despite being so, hosts the highest percentage of refugees in Lebanon: in Akkar, 200,000 Lebanese have been sheltering more than 150,000 Syrians, with the ratio between refugee and host population reaching almost 1:1. The poorest – welcoming the poor.

Between last Wednesday and Sunday, from September 4th until the 8th, the non-governmental organization Relief & Reconciliation for Syria (R&R) gathered, for the ninth year in a row, a summer camp for the children of Akkar. For all of them. Moments of shared faith – the Fatiha, the opening chapter of the Quran, and the Christian prayer of the Our Father, were recited in sequence – alternated with songs, political theatre performances, games, treasure hauntings, film screenings, and mutual exchanges of experiences.

Syrian and Lebanese children of different faiths gathered in Akkar for R&R’s ninth summer camp, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

Children enjoying a moment of fun playing sack race, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

“This year, the majority of children participating in our activities were Sunni. After the assassination of Pascal Sleiman [Lebanese Forces’ Coordinator in Jbeil] last April, and the waves of hatred against Syrian refugees that followed, Christian families operating with us became more reticent,” says R&R’s Founder and Secretary General Friedrich Bokern, better-known there as, simply, Fritz. You could clearly see how much locals appreciate him: originally from Germany, he has been living in Akkar for eleven years, since the establishment of the organization, back in 2013. He speaks Arabic fluently, and all the children turn to him as an older brother, a guide, often getting his name wrong. Freaks, Frid, they say, affectionately mocking the sound of his German r.

“Because of the regional tensions, we had to postpone the camp to the beginning of September. Last time we decided to do so, we were amazed by the huge difference in the climate. Compared to mid-August, when we usually organize the camp, the weather now is cooler, clouds come so low that you have the impression of walking above them, and a light, cold rain refresh our afternoons, every day,” he tells, while we approach our destination, driving from Bqarzla across Qantara, Gebrayel, Kousha, Rahbe, and Michmich. Yet the children don’t seem to notice it, caught up as they are in the enthusiasm of the departure.

Mountains of Akkar, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

R&R’s director, Friedrich Bokern, surrounded by the children of the summer camp, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

The war also prevented many international volunteers from coming and helping in the organization of the mukhayama, the summer camp. “As you can see, because we were lacking both international volunteers and the usual funds, the children that we were able to register, this time, are less than half of the previous years,” Fritz admits with a hint of discouragement. Then, regained the enthusiasm that suits him so well: “Yet, despite all the obstacles, we made it this time too. For them, for the children.” And he points to the caravan of buses that enters the mountain roads, the music at very high volume, the nearby villagers coming out of their houses – most of the time extremely modest – with a mixture of surprise and amusement. They greet, take photographs, give in to the children’s invitation to dance with them, raising their arms first with embarrassment, then with newfound ease, to the sound of the music. Despite all the obstacles, the poorest among the poor, in Akkar, the most forgotten of the forgotten ones, keep on celebrating the beauty of life.

The children of Akkar playing together during R&R’s ninth summer camp, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

Lebanon on the edge

And indeed above the clouds we arrived. Beyond the eastern mountains – Hermel and the Beqaa Valley: regions of transit and smuggling; beyond the northern ones – Syria: for most of the children, nothing but a name entangled with fear, inherited nostalgia, yet rejection. “I was one year old when we left, I can’t have memories there. All my life, I’ve only known Akkar,” says Ilaf, 14, originally from Homs, grown up in Majdala, while keeping an eye on her younger sister, Lyn, not bearing the birthmark of her place of origin. She was born in Akkar, ten years ago: knowing, though, she, also, is Syrian.

Among the effects of the coexistence – not always peaceful – between Lebanese Christian communities and the Sunno-Bedouin ones from Syria, the most evident is that of the newborns’ names, which have been facing an increasing contamination: despite the spoken accent always carrying a strong imprint of that of the parents.

Syrian and Lebanese girls of different faiths singing together, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

Two sisters playing three-legged race, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

What stands immediately striking is the extraordinary maturity of the girls. The poverty that forces their brothers to abandon school to start working early, especially in the harvesting of olives and apples that abound in the region, often sees them inhabiting the school classrooms alone, with a shift compared to what usual wretched, conservative contexts would predict: and that is that they, as women, would be denied the right to education.

At R&R’s multiple learning centers – located in Bqarzla, Kousha, Michmich, Rahbe, and Hissa – the trend of female school dropouts is notably reversed. “I am glad I am a girl because I can keep on studying,” Mira, 15, confesses, echoed by her peer Aya: “I want to go to school. That is my desire.” “It is always like that: when you go to school, you wait for summer holidays, and when it’s summer, all you do is wait for school to start again,” admits Fatima.

In a decade, R&R has been providing daily school support to more than 3,000 students in the region: yet, much more is needed. Public schools in Akkar are disastrous, from the buildings that do not protect students from winter storms and cold, nor from humidity and summer heat, and the risk of collapse at any moment – to classrooms lacking the equipment for scientific applications and many other activities. And with private schools limited to the very few who can afford them, education in the region ends up being a privilege denied to the poorest ones, mainly the Syrians.

Next to the need to work, one of the primary reasons for non-enrolment is the fear of discrimination. Nationality, religion, gender, as well as war factions’ support and their parents’ political standings, are among the factors of bullying that affect the generation of the sons and daughters of Akkar the most. Where to start when some of them can hardly obtain legal papers, and children of Lebanese mothers are still denied citizenship? Where – when a few kilometers beyond the northern borders, Alawite, Christian and Sunni communities are still torn by a 13-year-long war?

This is why the second R – R of reconciliation – is so important: to prevent the legacies of generations in conflict from grafting without reason into the innocent folds of childhood creativity. To prevent hatred from spreading endlessly. In the political theatre performance, the youth leaders stage discrimination in its crudest, most senseless essence: one of them, wearing a green mask, for being green, is ostracized, excluded, pushed to the ground. And those of them who dare to defend him; those who question the reasons for that violence, are forced to suffer the same fate.

This is the state of things. Yet, from the perspective of the children of Akkar, educated in peaceful coexistence in the difference, to be Syrian or Lebanese, Alawite, Sunni or Christian, corresponds to this: to a colour. The senselessness of racial, national, religious hatred – to the senselessness of hatred for a banal, insignificant color.

Children of R&R’s summer camp having a moment of rest while waiting for their lunch, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

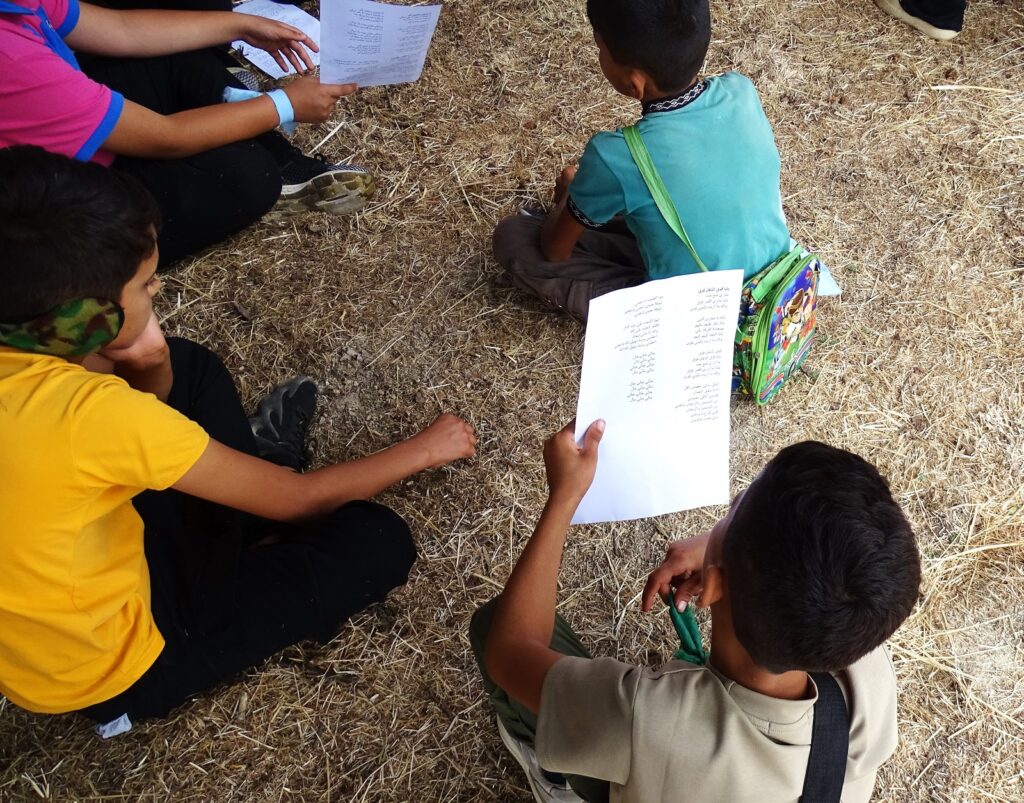

Children of R&R’s summer camp reading the lyrics of traditional Arab songs, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

Beyond humanitarian assistance

Fritz lives in Bqarzla, next to the regional capital Halba: among the Maronite villages in the region, it is the one hosting the highest number of Syrian refugees, both Sunni and Alawi – 400, for a village of 1,500 – who are mostly hired in olive production. It was there that R&R – with the help of more than 850 individual donors, as well as the support of the municipal council, other local and international NGOs, as well as the Syrian refugee communities of the surroundings – established its first Peace Center. Several local personalities soon became members of the organization’s first Steering Committee: the Sunni Mufti of the Akkar and other sheikhs, some of them from Syria; the Maronite Archbishop and local priests; the Greek-Orthodox Metropolitan; local NGO leaders, and also one Alawi notable.

The needs in the region, both marginal and marginalized, forgotten by most media and the international community, Bokern admits, are so big that everybody is helping each other. “Where others might see despair and deprivation, we see potential and the thirst of young people,” he wrote in the introduction of the 2022 Children’s Right Charter – a document that a committee of youth leaders from all of Akkar’s major communities drafted after conducting a representative survey amongst more than 700 children. And demanding, in eight points – from a decent life, to healthcare, safety and protection from exploitment, education, family, freedom of expression, respect of different identities, and the access to a worthy future – basic rights to live in dignity in a land they did not choose to be born in, nor displaced to: yet they sincerely, deeply love.

Location of R&R’s first Peace Centre in the North of Lebanon, with operational regions marked in red. Source: Relief & Reconciliation for Syria

Akkar, on the northern edge of Lebanon, is a mixed governorate where a majority of Sunnis are living side by side with Christians and Alawites: in this area, family ties have crossed the Syrian border for many years. The Syrian war affected the country severely, particularly the northern governorate: there, not only people barely survive, with tens of thousands of refugees living for more than a decade in tents, under the constant threat of eviction; but the political tensions between supporters and opponents of the Syrian regime have often led to open violence, most notably in the countryside of Akkar – where different neighborhoods have been under the constant threat of snipers and mortar grenades. Just as in the cities of Tripoli and Saida, and the Beqaa Valley.

Though in Akkar, where Christians and Muslims of different belongings and convictions have been living side by side, refusing the fate of a lost generation, the people of R&R saw the ideal place – no matter how difficult – to create a model that could also work inside Syria. And which is based on a multi-national, inter-faith post-war intervention, on the model proposed by Father Paolo Dall’Oglio. Better known as Abuna Paolo, the Jesuit priest, founder of the monastic community of Deir Mar Musa – a 6th-century monastery 80 kilometers north of Damascus – has been strongly involved in inter-religious dialogue and with the Islamic world. He was expelled from Syria in June 2012 for his critical positions on the Assad regime: and since he returned clandestinely in July 2013 to the north controlled by opposition forces, where he engaged in difficult negotiations for the release of a group of hostages in Raqqa, there had been no news about him. Among the hypotheses, a kidnapping which was never claimed.

Muslim corner of R&R Peace Center’s praying room in Bqarzla, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

Christian corner of R&R Peace Center’s praying room in Bqarzla, September 2024. A small curtain covers the Christian religious icons during the Muslim prayer’s time. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

Devoted to the task of ‘winning the peace’ in Syria, and well-aware that it will take more than mere humanitarian aid, the people of R&R – experts in peace-building, religious leaders, lawyers and psychologists, scholars, diplomats and intellectuals – believe there must also be reconciliation to prevent the country from spiraling into revenge and sectarian violence long after hostilities are officially over.

Fritz himself had direct experience in reconciliation efforts in the Balkans in the second half of the 1990s. “Already back then, we realized the contradictions inherent in interventions that are based solely on the humanitarian or solely on the peace-building approach,” he said in a previous interview, right after the establishment of the organization. “We must intervene in Syria now. Not only by bringing emergency humanitarian aid, but also by working to support internal reconciliation,” was his statement in 2013. Despite the tremendous pain and desolation that followed since then, the core idea of the mission has not changed. And, in Akkar, they’re fulfilling it: by welcoming the youth of different confessions and groups, both Syrian and Lebanese, to give traumatized children and adolescents a possibility to breathe; to play; to imagine an alternative, better life; to wish, and to hope for it to become theirs.

Two girls holding their hands at R&R’s ninth summer camp, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando

Children enjoying a walk in the nature of Akkar, September 2024. Photo credits: Valeria Rando