Joseph Tarab's departure beyond religion and encounter

It’s clear from the way things are developing that the Middle East is entering the era to be known as Pax Israeliana, or “Israeli peace”, established by the successive Syrian and Iranian phases, known in their Latin versions as Pax Syriana and Pax Iraniana respectively.

For the Land of the Cedars, a new period is opening up between Lebanon and its neighbor beyond our southern borders, whether through a return to the 1949 Armistice (which remained in force until the signing of the 1969 Cairo Accords) or the simple application of the provisions of the 1989 Taif Agreement.

With this beginning, it’s clear that many Lebanese men and women have been waiting for the right moment to return to Lebanon, to come back from their forced exile abroad, and pack their bags after a long period of uprooting. Among them, Lebanese Jews.

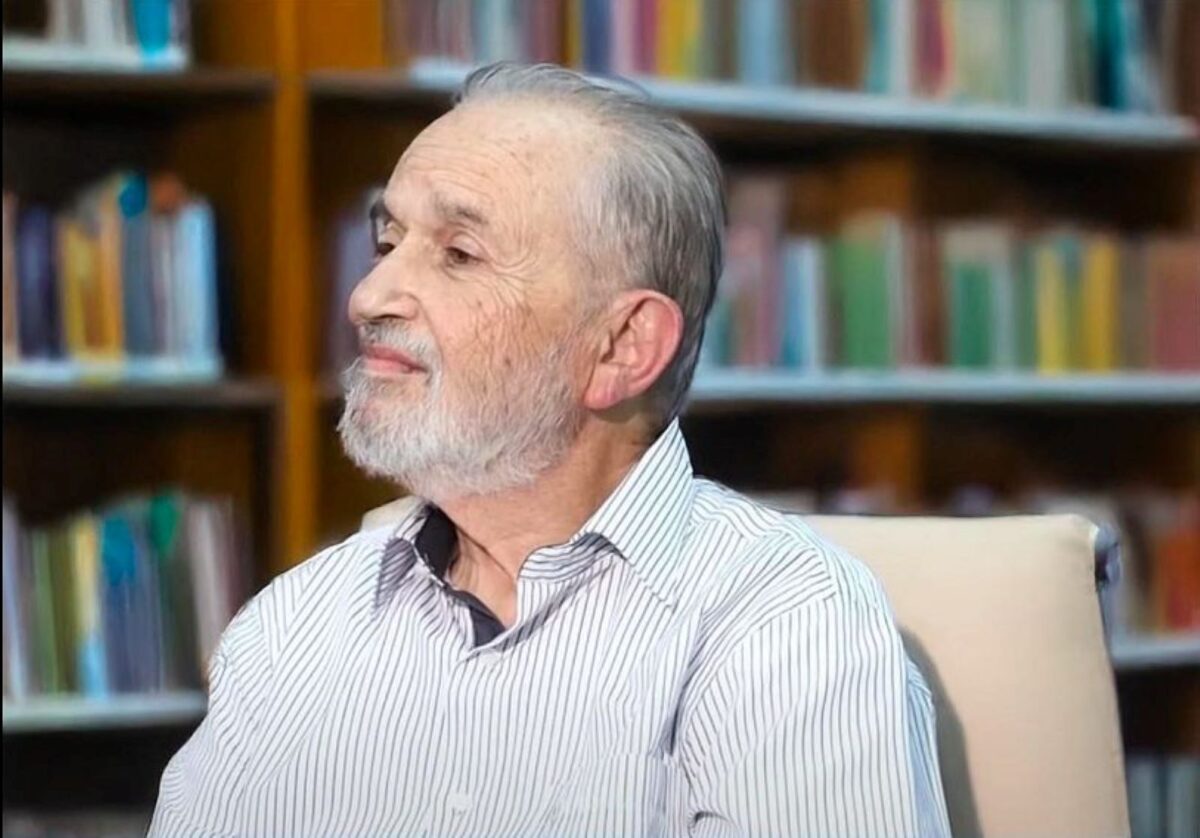

On December 31, 2024, one of Lebanon’s most openly Jewish residents passed away. An art critic, journalist and writer, Joseph Tarrab had long maintained that he lived on the bangs of the “Jewish community”. This was his way of reminding us that his words were his alone, that he represented no one but himself. And yet, Joe, a great friend of my mentor and friend Jalal Khoury, is often represented by his religious identity in the multitude of articles and statements celebrating his Lebanese cultural legacy. This is voyeurism, curiosity, and the desire to discover one of the eighteen religious denominations that make up the Lebanese mosaic.

Haggard Media

There are Zionists, there are Jews. Not all Zionists are Jews, and not all Jews are Zionists. Lebanese Jews – or Jews of Lebanese origin – whom I have met in Lebanon or crossed paths with abroad, hammer this point home. To this end, it would be necessary to echo their message, and thus contribute to reframing the popular amalgam between Zionism and Judaism. While images of Jewish pro-Palestinian demonstrations flooded social networks in 2023 and 2024, the Lebanese mass media ignored them. It was an opportunity, missed time and again, for the media to relay the powerful images of Jewish associations around the world demonstrating against the Israeli bombardment of Gaza, with Jewish participants brandishing slogans such as “Not in our name” and “Ceasefire now”. The media have chosen not to seize this opportunity to reframe the public narrative and redirect it in the service of the common good and civil cohesion.

Emphasizing the difference between Zionism and Judaism is necessary to prepare the return of Lebanese Jews with dignity, i.e., to avoid violent acts of vandalism and lynching. Speech being action, the recent past in Lebanon is no stranger to this violence, as Gad’s childhood testifies.

Lebanese Childhood

Gad Saad, professor, author and scientist of evolutionary behavior, was born in Lebanon 1964. In his own words, the Lebanese boy of Jewish faith had a happy childhood in Lebanon, albeit marked by some less-than-ideal situations from a Jewish point of view. Gad recounts three situations in which he witnessed hatred of Jews. Three examples that left their mark on the young man, showing how politics and current events influence people’s behavior and society’s thinking.

When Egypt’s President Gamal Abdel Nasser died, Lebanese took to the streets and launched into feverish lamentations. Six-year-old Gad sees a crowd pass by his house, chanting “Death to the Jews.” Stunned, he asks his mother, “Mom, why are they shouting death to the Jews? What have we got to do with it?”

In class, a few years later, the teacher asks each pupil to stand up and share what they wanted to be when they grew up. At nine or ten, one wants to be a doctor, another a footballer, another a policeman. One classmate stands up and says: “When I grow up, I want to be a Jew-killer”. The class applauds wildly.

The Lebanon war broke out in 1975, and some gunmen had Jews in their sights. Two blocks from Gad’s home, a Jewish family was shot dead. Businesses run by Lebanese Jews were looted, destroyed and burned. The message being clear, so many Jews organized their departure, including Gad’s family. When the pilot announced that the plane had left Lebanese airspace, Gad’s mother put the Star of David around her son’s neck and told him: “Now you can wear it. You don’t have to hide your identity anymore, and you can be proud of who you are.

And yet, it’s not a happy move for the eleven-year-old Lebanese, who doesn’t like his new city at all. Montreal is very dark, the white things falling from the sky annoy him, and it’s very cold.

Encounter with History

At the end of a party evening, at a conference in San Diego in 2023, a young woman apostrophized me:

- You’re the Lebanese guy, yes?

- Yes!

- I’m from Lebanon.

- You live in Lebanon?

- No, I live in Toronto. I’ve been watching you the last few days.

- You have?

- Yes, and last year too, during the 2022 conference.

- Well, why didn’t you say “Hi”?

- I wanted to be sure.

- Of?

Silence

- OMG! You’re Jewish and you wanted to see how I’d react to that!

Needless to say, we talked for a long time. It’s embarrassing that some Lebanese people are apprehensive about talking to their fellow citizens, fearing rejection, scorn, or even a backlash. A young man stood beside her. Surprise: a Jew, from Jewish parents, his father being Jewish Iraqi. We’ll talk about the Mizrahim Jews, the Orientals.

The highlight: returning to Lebanon and discovering the land of the forefathers to understand their origins and where they come from. Jews have lived in modern-day Lebanon for over two thousand years. In recent history, during and after the Second World War, Lebanon welcomed Ashkenazi families fleeing the Holocaust, and in 1941, some of Iraq’s Jews arrived in Lebanon, fleeing the pogrom against Jews in Baghdad. After the Israeli Declaration of Independence of 1948, Lebanon was the only Arab country whose Jewish population increased, and Jewish Syrians fled persecution there. Nevertheless, the fear of reprisals for actions carried out “in the name of the Jews” keeps haunting the Lebanese Jews.

History as Witness

Buoyed by their full membership of the Lebanese nation, Lebanese Jews resisted the efforts of Zionist recruitment movements and continued to serve in the Lebanese army. The weakening of the State’s authority and the increase in inter-faith conflicts led to the disintegration of the Lebanese nation, encouraging repeated attacks on Jewish individuals and interests. Emigration was the only option. Since then, scattered across Europe and the Americas, they have never ceased to ask the Lebanese they meet about Lebanon, dreaming of returning, and offering assistance to the Lebanese who are going through all the Lebanese crises.

Years have passed since the end of the war in Lebanon, and the condition of Jewish cemeteries continues to deteriorate, with synagogues left to decay. We Lebanese owe it to ourselves to preserve Jewish sites out of pride, dignity, citizenship, morality and patriotism, out of respect for the Lebanese citizen and our history. If only to ensure the solidity of these places, and if only for the memory of the dead of our Jewish fellow citizens, buried in Lebanese soil.

In Memoriam of Tarrab

Joseph Tarrab joined them on the first day of the year two thousand and twenty-five.

Some time earlier, I had asked him about the procedure for his burial. There is no rabbi in Lebanon, and the prayer is held discreetly.

Joe lived Lebanese in Lebanon, openly Jewish, without confining himself to a religious identity.

The grandson of one of the Grand-Rabbis of the Lebanese Jewish community, he was born in the year of Lebanon’s independence. Later, at a conference in Paris following the Six-Day War, he would say: “I speak as an Arab Jew. I speak as an Arab Jew from Lebanon, and I’m doing fine.” He will say that there is no Jewish problem in Arab countries, and that the problem, if it existed, was caused, not by the Arab states, but by the importation of foreign Jews into the region as part of the creation of the State of Israel, with its expansionist, eliminative culture, even at the expense of Arab Jews. Before becoming a full-time critic, Tarab was passionate about revolutionary ideas and was a fervent supporter of the Palestinian cause, calling on its leaders to adopt socialist ideas.

Joe attended the Collège Saint Jean Baptiste de La Salle, where young people shared a common Lebanese identity. In seventh grade, he joined Beirut’s ciné-club, a meeting place for the Lebanese intelligentsia, who exchange views after the film for two or three hours, sharpening their critical faculties to analyze the nuances of films – images, sounds, scenarios and performances. This is how Joseph Tarrab learned to read the cinematographic image, and developed his eye for reading the painting canvas.

His passion for culture led him to master several languages and immerse himself in the world of literature, theater and art criticism.

As a student at the École des Lettres, he worked with Jalal Khoury, Berge Fazlian, Roger Assaf, Paul Matar, Aline Tabet and others on contemporary theater. After studying economics, sociology, philosophy and demography, he began his career as a cultural critic in Paris in 1968.

While studying in France, he realized how much he missed the light of Lebanon, the sea and its clear horizon. Visiting Lebanon for the summer vacations, he stayed on and accepted an invitation from Georges Naccache, owner of L’Orient, to take charge of a daily supplement.

As a journalist, he returned home to Hamra Street at around four in the morning; the fear of anti-Jewish reprisals was foreign to him. In 1985, forced to leave Beirut, he settled in Jounieh, where he felt very much at home in his “normal” existence among Lebanese, Syrians, Iraqis and Saudis. The saying that the inhabitants of Keserwane reject foreigners proved to be false.

Over 150 paintings line the walls of his large house in Jounieh. These paintings stand alongside thousands of books and magazines, six thousand of which he will donate to the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik.

He would frequent artists, visual artists, sculptors, painters, authors, poets, musicians and theater makers, from their beginnings to their ascents, never meeting them before publishing his review to preserve his objectivity – a matter of principle.

Successively film critic and theater critic, he eventually devoted himself almost exclusively to art criticism. To his credit, he has written over 150 studies, lectures, prefaces and introductions to opuscules and catalogs of solo and group exhibitions. Monographs and art books on Stélio Scamanga, Paul Guiragossian, Norikian, Nada Akl, Salah Saouli, Missak Terzian, Hussein Madi, Jamil Molaeb, Mohammad Al Haffar, Rafik Sharaf, Juliana Seraphim, and photographer Varoujan Sétian. He contributed to monographs by Saloua Raouda Choucair, Hussein Madi, Shafic Abboud, Dorothy Salhab Kazemi and others. He will also take part in “Un Monde en Transition – D’Istanbul à Marrakech”, with Saad Kiwan, and “Le Cinquième Jour – Entre Ciel et Terre” with Mouna Bassili Sehnaoui. He will donate all his writings to the independent German research institute L’Orient-Institut Beirut.

According to him, Lebanese women artists are more important than men artists, because they come from a closed and harsh society, from which they freed themselves and overcame, to enter the artistic field and succeed, and each of them has her own style, innovation and excellence in her work that is not seen in men.

A humble and erudite man with a singular literary voice, Joseph Tarrab has chronicled the history of Beirut, from its golden age to its wartime periods, capturing in his writing the resilience and vitality of his people. His reviews reflect the perseverance of artists and the evolution of art in the midst of civil war and the good old days.

He leaves behind an exceptional intellectual and artistic legacy that reflects the history of the Lebanese people, he who always liked to remind us that he lives in the moment, the kind of person who turns the page and doesn’t let the past affect his future.

——

Explore more:

- Joseph Tarrab in conversation with Ricardo Karam: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=odVbJV7k37U

- Gad Saad talking about his childhood in Lebanon: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VM_1VoeVuc8

- Flâneries à travers les synagogues et les cimetières juifs du Liban par Sabyl Ghoussoub : https://orientxxi.info/lu-vu-entendu/flaneries-a-travers-les-synagogues-et-les-cimetieres-juifs-du-liban,1382

- The passing of critic Joseph Tarrab by Mohammed Houjeiri : https://www.almodon.com/culture/2025/1/2/رجيل-الناقد-جوزف-طراب-اليهودي-الأخير

- Hommage à Joseph Tarrab par Nelly Helou : https://www.agendaculturel.com/articles/hommage-a-joseph-tarrab

- Hommage à Joe Tarrab par Antoine Courban : https://middleeasttransparent.com/fr/hommage-a-joe-tarrab/