In Lebanon—and in much of the world—our political imagination is trapped. We are offered a familiar, almost ritualistic script: left versus right, resistance versus sovereignty, reformists versus establishment, and so on. We are made to believe that all political thought must fall somewhere on this rigid axis, and that to be in the “center” is merely to stand in the middle of the battlefield, trying to appease both sides.

But this reading of centrism is not only incorrect, it is profoundly dangerous. It reduces political agency to a matter of balance, when it should be a matter of vision. It treats centrism as indecision, when in reality, it is discipline.

True centrism—what I would call radical centrism—is not a midpoint. It is an entirely different dimension of political reasoning. It does not oscillate between extremes, but rather refuses to be bound by them. It does not simply pick and choose elements from the left and right. Instead, it asks whether the frame itself is broken, and then tries to rebuild it.

Centrism, in this deeper sense, is not neutrality. It is meta-positioning. It is a political consciousness that sees through the performance of partisanship and asks harder, structural questions. When ideology becomes a substitute for strategy, centrism resists. When populism becomes a weapon, centrism builds process. When emotional narratives blur reality, centrism brings clarity.

This is not moderation for its own sake. In fact, it is often uncomfortable; because it refuses the simplicity of slogans. It takes courage to be called naive by radicals and complicit by ideologues, simply because you refuse to fight a war on their terms. But in that refusal lies power.

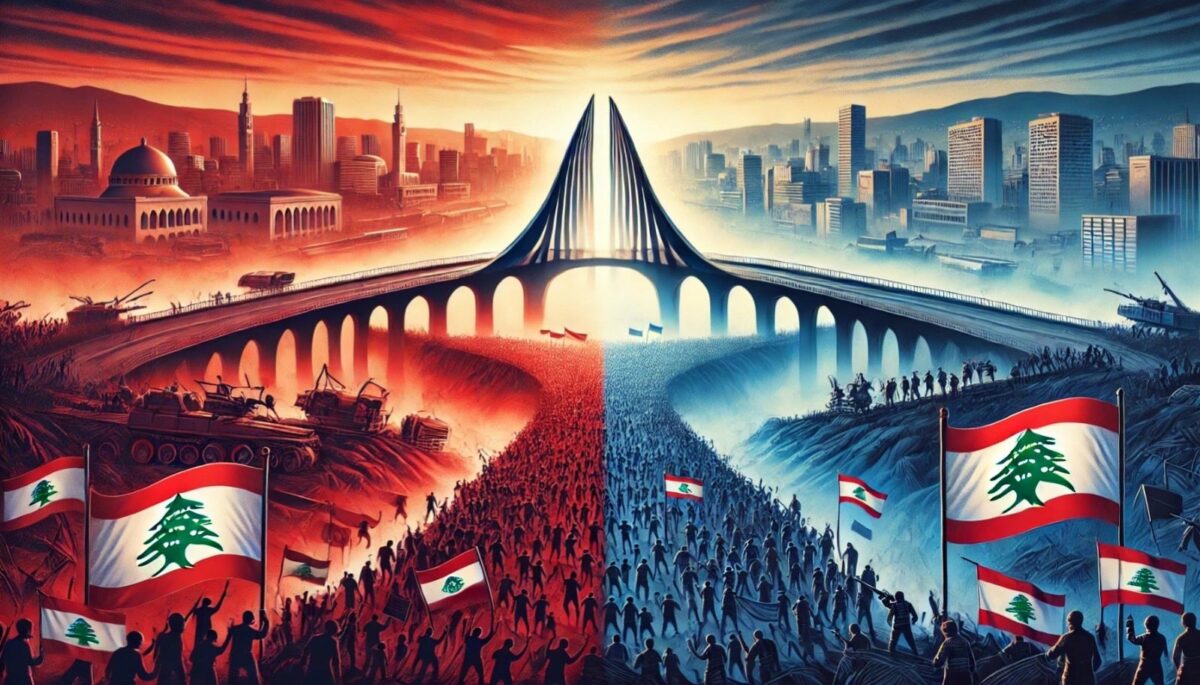

Nowhere is this more relevant than in Lebanon.

Our crises are not just economic or institutional. They are cognitive. We are locked into binary ways of seeing ourselves, our history, and our politics. We recycle the same accusations, the same allegiances, and the same symbols, expecting different outcomes.

For some, resistance is sacred and non-negotiable. For others, sovereignty is a litmus test of belonging. For many, politics has collapsed into identity: you are what you vote, who you follow, or what you oppose. In that landscape, centrist thinking is treated with suspicion; too calm to be revolutionary, too measured to be loyal, too nuanced to be “real.”

And yet, if we are to move forward, we need to think differently.

We need to build political movements not on anger, but on architecture. We need to replace ideological rigidity with systems thinking. We need politics that can hold complexity, admit contradiction, and design for coexistence, not in spite of difference, but because of it.

Centrism, in this sense, is not weakness. It is a form of strength that comes from resisting the pull of extremes. It does not retreat from conflict, but rather insists on better arenas to resolve it. It does not deny identity, but refuses to weaponize it.

The Lebanese center is not soft. It is sober. It is where we trade shouting for dialogue, allegiance for accountability, and performance for policy. And when the noise of populism dies down, as it inevitably will, the center will be the only ground stable enough to build on.

It is time we reclaim that ground, and stop mistaking noise for power.

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a Political Psychologist and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution at the Lebanese American University.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW