Why Hezbollah still echoes Iran, even after being left behind

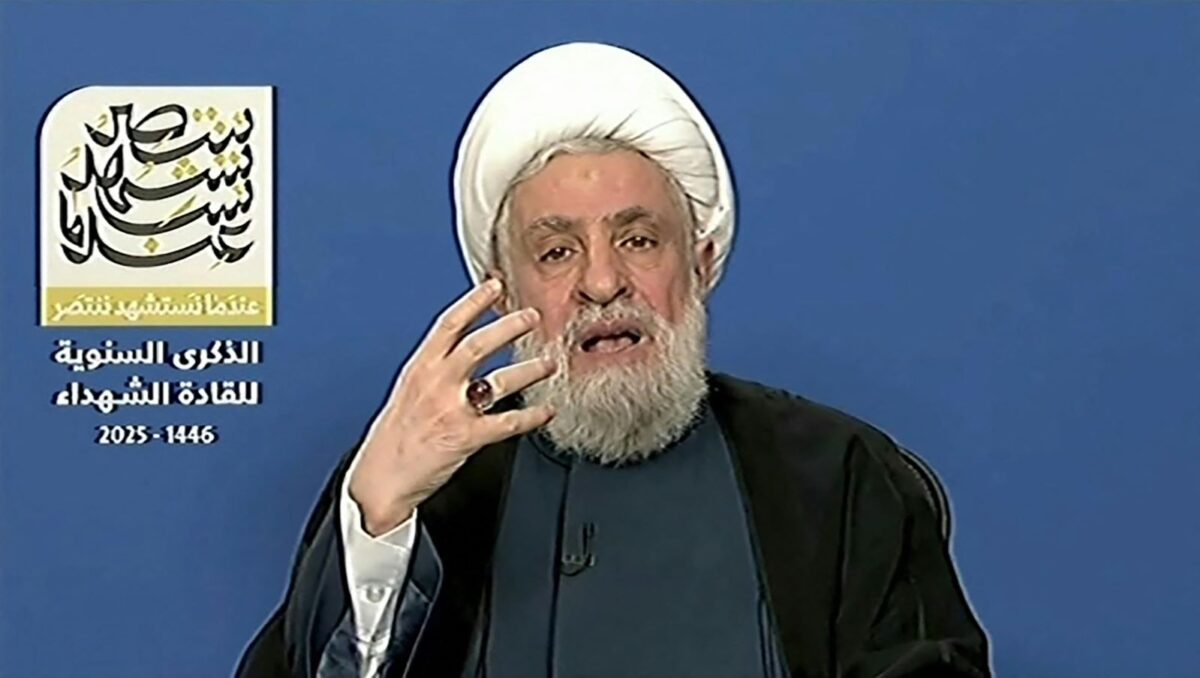

Over the past week, Hezbollah made one thing clear: disarmament is not only off the table, it’s a threat-worthy offense. Senior Hezbollah’s official Wafiq Safa bluntly stated that those who demand Hezbollah’s weapons are not living in the real world. Naim Qassem, the group’s Secretary-General, went further: there would be no talks, no compromise, and no room for discussion on the matter. Any attempt to push the issue, he said, would be tantamount to collusion with the enemy.

This is not the rhetoric of a national party open to dialogue. This is the rhetoric of a group doubling down on deterrence through intimidation, issuing threats not just to Israel, but to fellow Lebanese. And it came as Iran’s ambassador in Beirut denounced disarmament as a “clear conspiracy”, drawing direct lines between military weakness and the fates of Iraq, Syria, and Libya. The timing was no coincidence. Iran is sending a message and so is Hezbollah.

But the irony is striking. Only weeks ago, as the U.S.-Iranian backchannel worked toward a regional ceasefire, it was widely believed that Iran had offered up Hezbollah as part of the bargain. Tehran, cornered economically and diplomatically, seemed ready to pull back its regional proxies to avoid escalation. And Hezbollah, by most accounts, complied. It paused fire. It toned down its media machine. It signaled readiness for quiet.

So why, now, this sudden return to maximalist rhetoric? Why the open threats? Why does Hezbollah sound more like the Revolutionary Guard’s outpost than a Lebanese actor navigating post-war reconstruction?

Because despite being briefly sidelined, Hezbollah remains deeply tethered to Iran; not just politically, but existentially. And this recent escalation shows just how little independence it truly has.

Hezbollah’s threats last week weren’t about defending Lebanese sovereignty. They were about defending Iran’s deterrence strategy from unraveling. When Iran signaled its willingness to trade regional calm for diplomatic breathing room with the U.S., Hezbollah didn’t rebel. It paused, obediently. But when Iran’s rhetoric flared back up, Hezbollah snapped to attention, not because it had to, but because it doesn’t know how not to.

This is not the behavior of a resistance movement. This is the behavior of a client force, one whose fate is too entangled with its patron to ever genuinely pursue a national path.

And yet, the contradiction deepens.

Lebanon’s current leadership—President Joseph Aoun and Prime Minister Salam—have made serious overtures toward reviving a national defense strategy. Not just as rhetoric, but as a path forward for sovereignty, for de-escalation, and for finally resolving the state-within-a-state reality that has paralyzed Lebanon for decades.

Their position, while measured, is consistent: all weapons must eventually fall under the authority of the Lebanese state. This is not a revolutionary demand. It’s a constitutional one. And in any functioning democracy, it would be the starting point of any national dialogue. But instead of a conversation, they were met with a threat. Instead of negotiation, with a warning. And instead of a partner, they faced a group ready to treat fellow citizens as enemies simply for wanting a state monopoly on force.

This isn’t about south Lebanon anymore. It’s not about resistance. It’s about power.

Hezbollah’s refusal to even entertain the idea of disarmament even after Iran nearly gave them up should tell us something fundamental: that the group is not acting out of strategic necessity, but out of institutional dependency and existential anxiety. It knows that without arms, it cannot dominate. Without domination, it cannot exist as it currently does. And without Iran, it has no shield.

So, what happens when that shield starts to crack?

That’s the real question. Because while Iran may still benefit from Hezbollah’s presence, it has shown it is willing to bargain with it. And Hezbollah, rather than reevaluate its position in light of that fact, has instead chosen to prove its loyalty even more aggressively as if trying to remind Tehran of its usefulness.

But in doing so, Hezbollah exposes a deeper truth: that its allegiance to Iran is no longer strategic, it is psychological. It is the loyalty of the betrayed who still begs for relevance. And that loyalty is now being demanded of an entire country.

Hezbollah may continue to pledge loyalty to a foreign capital. It may threaten, deflect, and double down on a fantasy of divine resistance. But the only loyalty that will matter going forward is the loyalty to a Lebanon that speaks for its people, not for a proxy war. A Lebanon that fights for the sovereignty of its state, not the survival of a militia. A Lebanon that protects its citizens’ interests, not the priorities of external patrons cloaked in ideological excuses. No matter how deeply entrenched, no matter how long justified, the age of subcontracted sovereignty is coming to an end. And those unwilling to evolve with it will find themselves increasingly isolated, not by foreign powers, but by the very people they claim to defend.

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a Political Psychologist and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution at the Lebanese American University.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW