The so-called “Axis of Resistance” is mired in deep moral and political crises, none more telling than its astonishing ability to lie with abandon. Propaganda has become the bloodstream of its daily discourse—manufactured rumors repeated until they sound like truths, repackaged into heroic narratives under slogans such as “the most honorable people.” Anyone daring to question this delusion is branded a traitor.

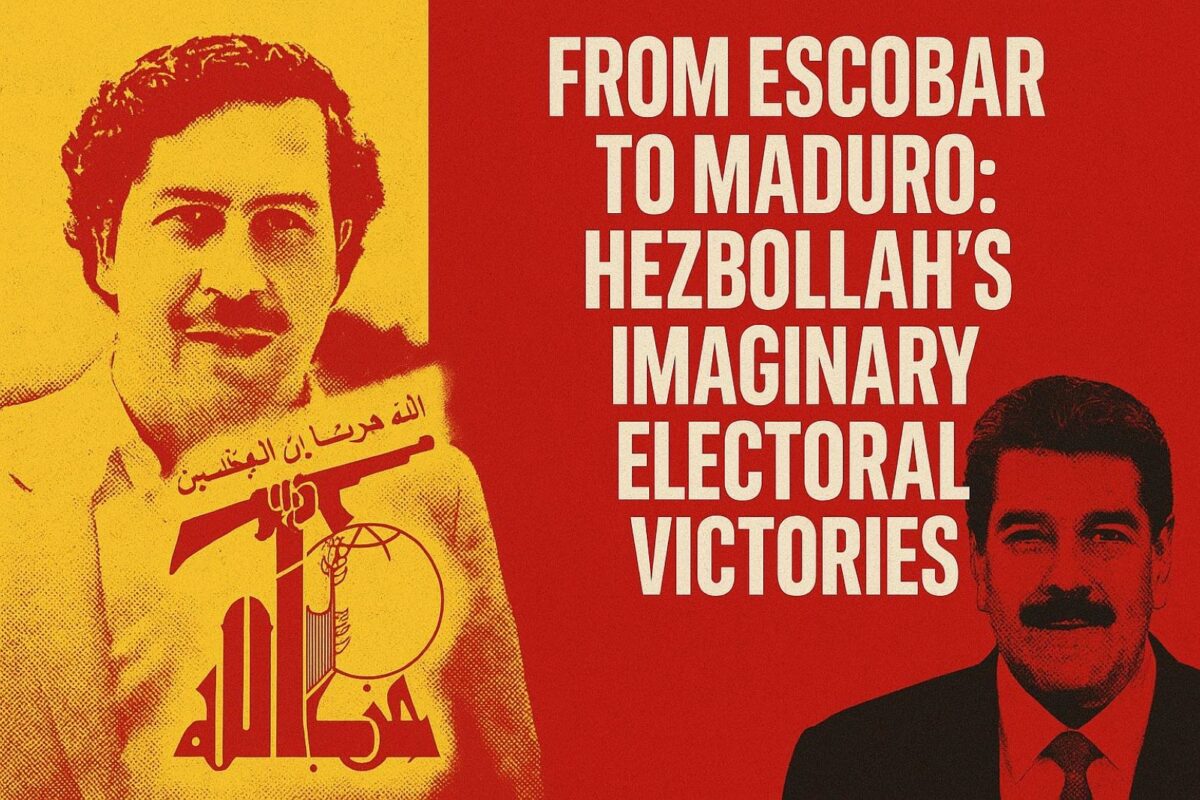

This estrangement from reality is not new. It is structural. The axis has long transformed defeats into rhetorical victories, military losses into symbolic “points” in what it now calls the “battle of consciousness.” Just last week, a Hezbollah affiliate appeared on an Arab media outlet insisting that the axis had not lost the war, but merely “lost a round on points.” As proof, he cited supposed electoral “victories” in Colombia, Brazil, and Venezuela. The claim, predictably, became instant fodder for mockery on social media.

Whether this was a slip of the tongue or a scripted “talking point” circulated by beeper or WhatsApp group, it exposes the mindset that drives Iran and its regional clients: a psychology built on denial, wishful thinking, and ideological fantasy rather than the hard facts of geopolitics.

Hezbollah and the remnants of Cold War militants still cling to the illusion that global powers—Russia, China, or the BRICS bloc—will one day swoop in to crush American hegemony. All it takes, they say, is “patience” and “faith in the cause.” Yet this reveals a profound ignorance of today’s international order.

China, above all, has no interest in Iran’s adventurism. For Beijing, prosperity comes not from militarizing the Middle East but from stability, trade, and open markets—conditions wholly at odds with the perpetual conflict that the axis thrives on. Russia, meanwhile, is mired in its own quagmires and treats Tehran with cold pragmatism. Moscow does not rank “liberating Palestine” or empowering Hezbollah among .

The claim that Latin America has somehow fallen under the sway of “resistance culture” is equally misleading.

In Colombia, authorities designated Hezbollah a terrorist organization in 2020 after the group carried out terrorist and criminal operations on its soil, including attacks on Jewish communities and U.S. interests. President Gustavo Petro may have a past in a Marxist guerrilla group, but he renounced violence in 1989 and embraced democratic politics. His trajectory was consolidated with the 2016 peace accord that disarmed the FARC and integrated it into civilian life—precisely the kind of disarmament Hezbollah refuses to contemplate. To describe Colombia as part of the resistance axis is ideological fiction at best.

Brazil under President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva offers a similar case. Lula is a long-time supporter of Palestinian rights, but Brazil has dismantled Hezbollah’s financial and criminal networks and arrested Lebanese expatriates tied to narcotics smuggling and terror plots. Sympathy for Palestinians does not translate into membership in the Lebanese chapter of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard.

Venezuelan strongman Nicolás Maduro is perhaps the axis’s most celebrated “ally.” Yet here, too, reality is sobering. Maduro lost the recent election by a wide margin, clings to power through repression, and leans on Cuban mercenaries paid from Venezuela’s plundered resources. This is not resistance. It is dictatorship disguised in the language of sovereignty and anti-imperialism.

What stands out most in the rhetoric of the axis is its absolutism, its collective hallucination. It refuses to acknowledge losses, wrapping death, destruction, and sectarian carnage in the costume of divine struggle.

This fixation on “winning on points” has a bloody price. It produces phantom victories while rivers of blood run in Gaza and southern Lebanon, where ideological dreams are buried under the rubble of homes and the bodies of children.

In the end, the political mind of the axis sees the world through a single, distorted lens: denial and flight forward. It cannot read global shifts or grasp the limits of its power. And so it clings to an illusion of “points” in battles it has already lost. The “resistance project” is not just failing. It is dead—only its burial remains

This article originally appeared in Nidaa al-Watan

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah