Human rights organization Equality Now newly released a landmark report, titled ‘In Search of Justice’, revealing how legal systems in all 22 League of Arab States countries are failing to define and prosecute rape adequately. NOW Lebanon has interviewed one of the report’s authors, Gender Advisor for the MENA region, Paleki Ayang, on the challenges that addressing rape in the Arab world entails: from marital rape, child marriage, to the use of force and the issue of consent, and the danger of a reductive and stigmatizing terminology

The only way rape is classified, in several countries of the League of Arab States, is vaginal penetration by a penis: other forms of non-consensual penetration – not vaginal, not by a penis – are categorized as lesser offences, with significantly lighter penalties: ‘indecent assault’, for the perpetrator – ‘violation of honor’, for the victim. The ugliness of this discourse also lies in having to define, categorize and describe the legal technicalities of a violent act that should simply be called ‘rape’ and punished as such. But this is not the case in this world, and especially in this Arab world: where marital rape, for instance, is never explicitly criminalized – and sex in marriage is considered as a woman’s obligation, rather than a pleasure.

Several countries of the Arab League permit marriage under 18 years old, with some allowing girls to be wed at nine, while others set no minimum age: and as child marriage laws are usually poorly enforced, this often provides impunity for the rape of children within marriage. In Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria, a rapist can – still today – escape prosecution by marrying his victim. And forcing his child-wife to sex will not, in any Arab country, be even remotely compared to rape: even if this is the case, given that a minor cannot give consent. But instead of on the absence of consent, Arab penal laws often define rape based on physical force: and when proofs of physical resistance fail – sometimes because the survivor denounces months after the event, sometimes because other means of coercion are used, sometimes because the victim is drugged, disable, or in a disadvantaged position of power – cases are usually dismissed. And the rapist remains unpunished: systematically.

These are some of the findings of the latest report of Equality Now, a worldwide human rights organization dedicated, since its inception in 1992, to securing the legal and systemic change needed to end discrimination against all women and girls, everywhere in the world. Legal analysis collected in the report ‘In Search of Justice: Rape Laws in the Arab States’ – released last Tuesday, September 9 – has identified how all 22 League of Arab States (LAS) countries are failing to define, prosecute, and address rape adequately; how their discriminatory laws perpetuate harmful sexist stereotypes and victim-blaming; and how, compounded by weak and inconsistent enforcement of laws, women and girls are being left without adequate protection or access to justice.

“But changing the law is not enough,” said from Cairo, on the eve of the launch, Paleki Ayang, one of the report’s authors. South Sudanese based in Kenya, she joined Equality Now in November 2021 as a Gender Advisor for the MENA region, implementing programs in the Middle East and North Africa, mostly on family law. She also works on advocacy around ending sexual and gender-based violence, as well as promoting political participation in Palestine and Egypt. “What we realized while carrying out our research, is that in many cases laws can be written in a certain way, but the reality on the ground is completely different. That’s why we need a change in the justice system and in the system more broadly. All these reforms go hand in hand,” she continued.

After having conducted similar reports in other regions – last year in Africa – ‘In Search of Justice’ applies the same methodology to the Arab world: authors have mapped the 22 LAS countries and then examined their compliance with international human rights’ standards, particularly the UN CEDAW convention of 1979, a treaty also known as the ‘International Bill of Rights for Women’, which defines discrimination against women and establishes an agenda for eliminating it by requiring states to incorporate the principle of equality into their legal systems. “The main purpose of the report is to expose the legal gaps of the Arab states’ systems,” continued Ayang, “such as the absence of consent-base definition of rape, the absolute non-recognition of marital rape, the existing exceptions in the law that legalize child marriage, while at the same time we want to provide the government and civil society with concrete evidence-based recommendations. We are trying to spark legislative and policy reforms that could bring the national framework in these 22 countries in line with survivors-centered justice.”

Part of Equality Now’s global work to end sexual violence, the report covers all 22 LAS Member States: Algeria, Bahrain, Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen – with a deeper evaluation of Egypt and Lebanon as case studies to attempt to highlight stark disconnects between theoretical laws and the harshness of reality in police stations and courts, where survivors are frequently confronted by disbelief, rape myths, and procedural hurdles that deter reporting and obstruct cases from advancing. To do so, authors applied a mixed methodology merging the desk research and mapping of the Arab states’ legal literature, with the interviewing of lawyers, judges, and survivors, the latter helping explain some of the issues that the report reveals theoretically.

As Ayang explained, “partners in Egypt and Lebanon provided us with real stories that they have interacted with on the ground,” such as that of Isatta Bah, a 24-year-old migrant domestic worker from Sierra Leone who fled abuse by her employer in Lebanon. Domestic migrant workers in Lebanon are particularly vulnerable to abuse – including rape and sexual violence – and face additional barriers to justice due to the legalized system of slavery, known as kafala, which forces them into complete dependence on the sponsor, a Lebanese man or woman, who often retains their documents. After escaping her employer, Isatta and five other migrant workers were raped by a group of men while seeking transport. Fearing reprisal and lacking legal documentation, she did not report the crime: a tragically illustrative case of many.

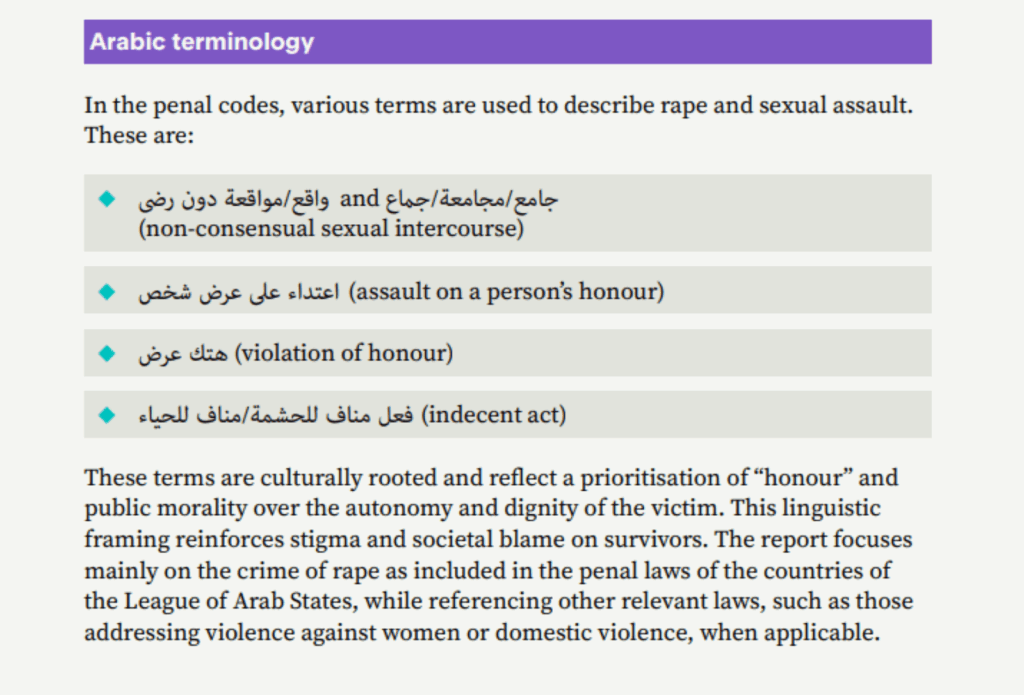

The dangerous power of a reductive and stigmatizing terminology

“One of the most significant challenges we have identified in the process is the one about terminology,” Ayang explained. “In most countries, the definition of rape is based on penal-vaginal penetration using force. Of course we know that rape can happen in different ways, doesn’t have to be a penis penetrating a vagina for it to be rape. But in most countries the definition of it is so narrow, that the issue of consent is not even put into consideration: whether the survivor consented or not, it is always absent from the definition. If a woman freezes in fear, or complies under coercion – a weapon or a threat – she is not protected by the law, and that’s a huge problem.”

Yet, according to international law, rape refers to all acts of penetration, however slight, of a sexual nature with any bodily part or object, without the full and informed consent of the victim: a definition centered, as it should be, on the lack of free, voluntary and willing consent – rather than the use of force or violence, covering engaging in non‐consensual vaginal, anal or oral penetration of a sexual nature of the body of the victim by the perpetrator using any bodily part or object.

Any of these kinds of rape are to be considered a crime against bodily integrity: however, they are most of the times framed in the language of honor, moral, and decency. It is the case, for example, of Lebanon and Syria, where rape is categorized under laws protecting public morals; in Egypt, some types of sexual violence – which in reality amount to rape – are labelled as ‘indecent assaults’. “But when you call a rape ‘indecent assault’,” commented Ayang, “it automatically reduces the crime, that becomes a simple harassment. And the penalty is also reduced. The result is that a hierarchy of crimes is created, even though according to international standards, these are all rape.”

Especially in Arabic, then, the definition is particularly stigmatizing. ‘Violation of honor’. ‘Assault on a person’s honor’. ‘Non-consensual sexual intercourse’. ‘Indecent act’. Never اغتصاب, ‘rape’. In a case brought before the Egyptian Court of Cassation, a husband was found to have sexually assaulted his wife, the victim, against her will, while he was one of those who had authority over her. He assaulted her by beating her, removing her clothes and having anal sexual intercourse with her. He repeated this act, causing her injuries as stated in the forensic report. But because the penetration was not vaginal – and because the victim was the aggressor’s wife, despite being a minor -, the court did not consider it rape.

Shifting the focus away from the survivors bodily integrity, such approach does nothing but reinforce patriarchal notions of family honor. And apart from being problematic per se, it also fuels stigma: as you will find young girls portrayed as if they damaged their family reputation – being furtherly attacked with the charge of zina, adultery – instead of acknowledging that they have been violated. And because they are the one to blame, whose words must be treated with caution – after all, it is indecent – it is the victims’ version of events that is subjected to proof-finding. Their entire body – instead of being cared for – forced to endure yet another violent inspection.

A screenshot from Equality Now’s report, ‘In Search of Justice: Rape Laws in the Arab States’, under the introductory chapter: A note on terminology (p.6). Source: Equality Now

The process of undergoing forensic examination is often deeply traumatic for survivors: not only victims are denied emotional support, legal accompaniment, or privacy during these procedures, but police – most of whose officers are men – frequently fail to inform them about how to preserve evidence and the procedure to follow with respect to examinations.

The testing, then, is often carried out in an intrusive manner that does not meet international health protocols and standards: “It’s usually a terrible experience,” commented a lawyer from Egypt. “The medical examination process can also be invasive and distressing. Psychological support is missing entirely from the process,” she stated. “In some cases, when forensic doctors examine the victim, there are two problems that arise: first, they prevent anyone from being with her – even though the law permits accompaniment. Second, the examination can be humiliating, especially if doctors judge the victim’s morality and go beyond what the investigation requires, such as performing unnecessary anal examinations.”

The logic of forensic tests is indeed brutal: because if the hymen is intact, the woman is believed a virgin – her honor untouched – but she is not believed a victim of rape; if not, she might be legally taken into consideration, as a penetration has surely happened, but it is her social case that collapses. If she was already married, if she was sexually active before marriage, if she was not a virgin; if there was no hymen, or the hymen was elastic or whatever reason: proving rape becomes nearly impossible, because it cannot be proven that the girl was a virgin before the assault. And in a moment, the examination to prove a rape had happened becomes a virginity test: that has at its center – at the center of the investigator’s judgmental attention – the chastity of the victim, doubly accused, doubly violated. Worse, stigma follows her into the courtroom, casted doubt with the unspoken but constantly implied question: If you weren’t a virgin, how can we know you didn’t consent?

In the case mentioned before, the court imposed one year of imprisonment with hard labor to the aggressor, but eventually suspended the sentence. If the court had been able to impose the regular penalty for sexual assault outside marriage as stipulated in the Egyptian Penal Code, Article 268, punishment would have been rigorous imprisonment up to a life sentence. As it was, the court applied mitigation to the penalty invoking Article 17 – often used to reduce sentences on perpetrators of ‘honor’ crimes sometimes without obliging the judge to justify his decision – to suspend the execution of the sentence. By contrast, the same article is legally prohibited from being used in cases of drug crimes: when honor is involved, tribes or families of the parties may intervene to settle cases without any criminal prosecution – like the case of so-called ‘honor killings’ used to conceal cases of rape, including incest, with families opting to silence victims through murder rather than risk exposing perpetrators. The use of these mitigations to shield rapists not only diminishes accountability, but in practice legitimizes both murder and sexual violence, thereby reinforcing a broader culture of impunity – in front of which written laws can do nothing but yellow and gather dust.

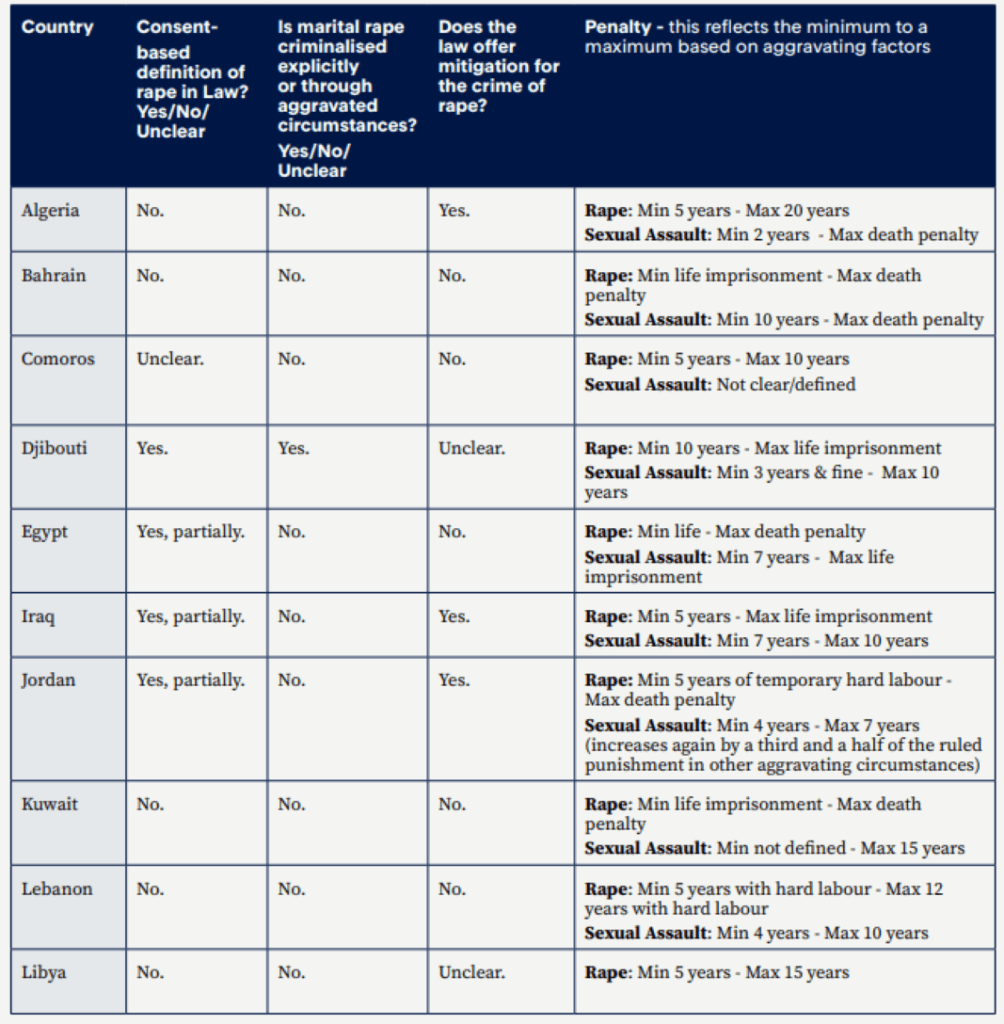

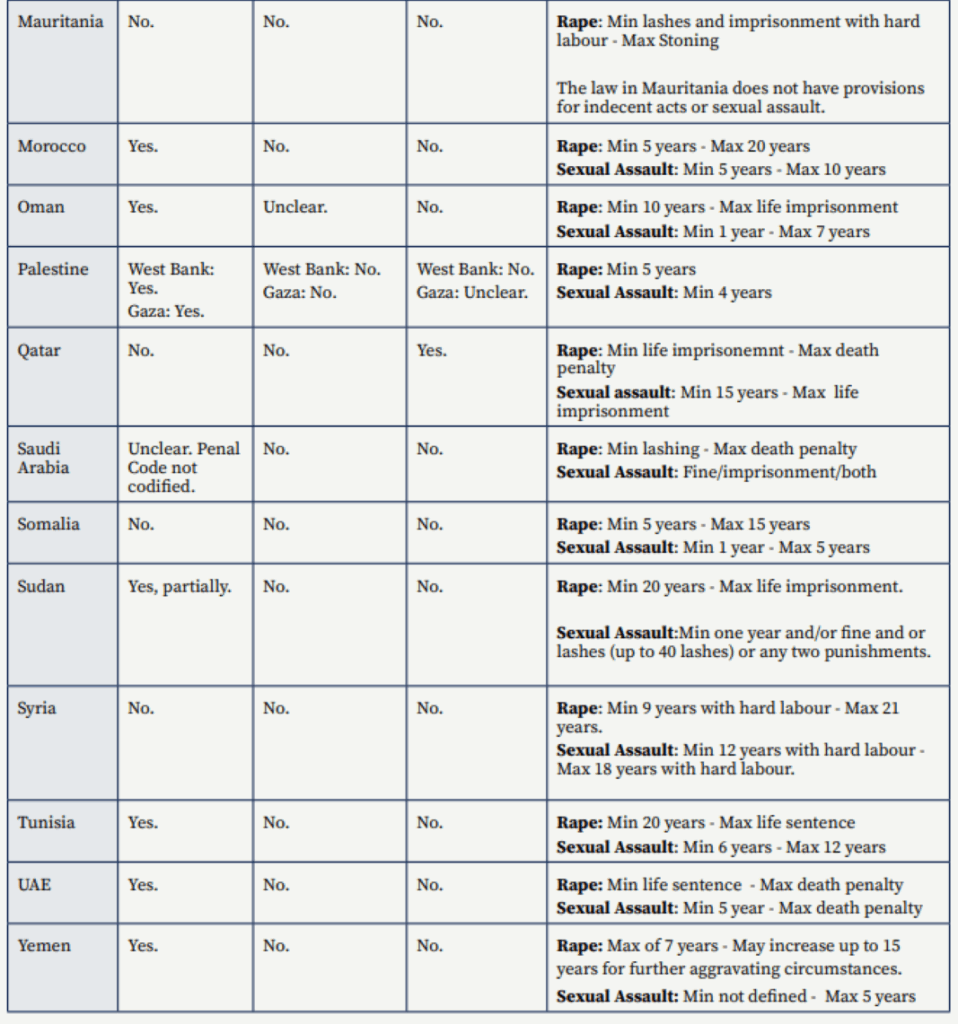

The arbitrary subjectivity of penalties

On the definition of rape depends the severity of the punishment inflicted: and since each Arab country’s criminal code uses a different definition of rape, the punishment imposed on the aggressor also varies according to the nuances of indecency attributed to each case. It is worth repeating: this is always to the detriment of the victim, who remains isolated not only legally, but also socially. It is the law of surveillance and punishment, that the weaker a state is, and with it its judicial system, the more the power of social, tribal and family control creeps in and strengthens. And with it, stigmatization.

In most Arab countries, for example, where most crimes that according to the CEDAW Convention would undoubtedly fall into the category of rape – any non-consensual and non-vaginal penetration can be punished with the same negligence as sexual harassment and consensual touching in public. It goes without saying that if rape and consensual touching in public are legally equal, the punishment imposed for the two acts – the first an objective crime, the second an indecent act according to the discretion of a fallacious and arbitrary moral norm – paradoxically ends up being the same. And in two different countries, the same crime can be merely bypassed or punished with the death penalty.

A screenshot from Equality Now’s report, ‘In Search of Justice: Rape Laws in the Arab States’, under the Annex 1: Definitions and penalties for rape and sexual assault (p.56). Source: Equality Now

A screenshot from Equality Now’s report, ‘In Search of Justice: Rape Laws in the Arab States’, under the Annex 1: Definitions and penalties for rape and sexual assault (p.57). Source: Equality Now

“This absurd gap in penalty is related to the definition of rape itself,” commented Ayang, referring to the cases of Lebanon and Kuwait. “In some countries, the penalty can depend on the age of the girl: if she is between 15 and 18, the penalty is a certain amount; if she’s below 15, it is harsher. Or, if you are related, the penalty differs again. If the penetration is anal or vaginal, it is also different. And if weapons are used, it takes the crime to yet another penalty.”

In a context of conflict, Ayang explained, such as Palestine and Sudan, rape is considered a weapon of war – and thereby falls under the frame of international law, with the ICC and other international bodies adopting their own jurisdiction. But if use of weapons happens outside conflict – for example in a robbery or a feud – depending on the country, it can be considered as an aggravating circumstance, but not serious enough to condemn the act as rape. “Also consider that when weapons are involved, because there is a threat to the victim’s life, her body hardly ever carries the physical evidence of resistance. That’s why we believe that the issue of physical evidence should not be taken into consideration: it’s a very contentious matter, and it shifts the focus from consent to the use of force to define, thus persecute, rape,” she added.

But if the penalty range is so wide, it is not only because of the subjectivity of definition, but also due to historical reasons. Laws, in most LAS countries, are inherited – and their progression is extremely different: some lean towards shari’a-based criminal law, like Saudi Arabia and previously Sudan; others adopt colonial law – either French, English or Turkish. It’s a mixed approach depending on the history of each country. “But the common thing is that all these laws are problematic – being them religious or colonial,” said Ayang.

In Palestine, for instance, the Jordanian penal law that existed before 1967 continues to apply in the West Bank, as amended by subsequent Palestinian legislation – while the Egyptian penal law that existed before 1967 continues to apply in the Gaza Strip, as amended by subsequent Palestinian legislation. Instead in Syria, where the latest regime-change has pushed the country towards a new Islamist drift, a new constitution is expected to be drafted by the Transitional Government by 2025. Equality Now had already stopped collecting the data when the Assad regime fell in December 2024, yet, according to the legal experts, “social norms remain the same regardless of a change of government, because the people themselves have not changed,” commented Ayang. “A change of regime only regards the government. And yes, as long as the government massively changes reforms, society will ultimately be impacted,” she went on saying, “but something we’ve been extensively discussing is still very relevant in the case of Syria, even if there was a huge political change: which is the notion of honor, of rape as a crime against family and decency. This, in the Syrian society – either at a nuclear or at an extended level – has not changed.”

An urgent call to action

“We urge League of Arab States members to act now. Sexual violence laws need urgent and comprehensive reforms that are grounded in consent, survivor dignity, and enforcement mechanisms that actually work,” stated Dima Dabbous, Equality Now’s Representative in the Middle East and North Africa. “Access to justice is hindered by excessive evidence requirements based on narrow legal interpretations of rape, such as those requiring proof of physical force. Various forms of sexual violence are not adequately recognized legally, and critically, no Arab League country has explicitly criminalized marital rape. A few still permit rapists to avoid prosecution by marrying their victims” – as it’s the case for Algeria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria – “although some countries have recently closed ‘marry your rapist’ loopholes.”

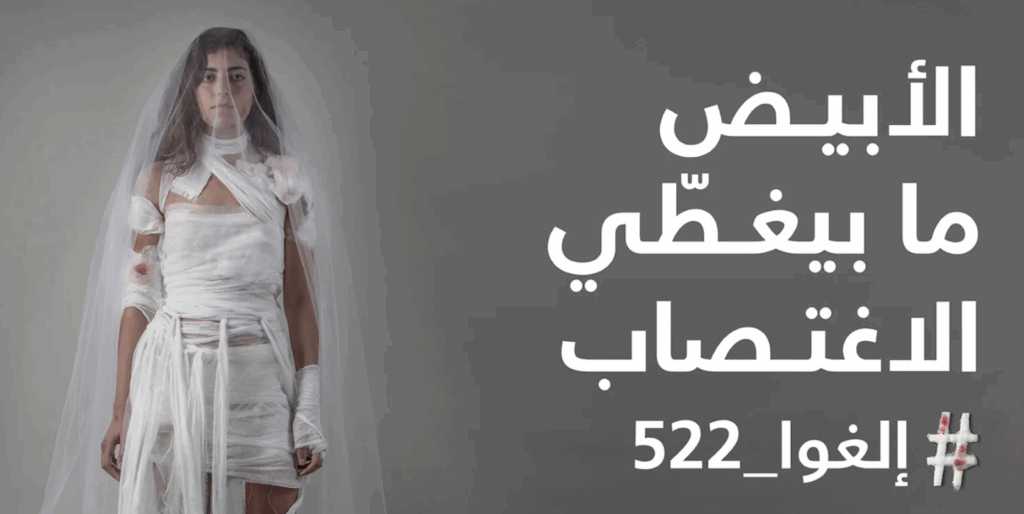

In the specific case of Lebanon, for example, Article 522 of the Penal Code allowed the rapist to escape punishment if he married his victim: repealed in 2017, after consistent and targeted campaigning by the women’s rights movement – noteworthy was ABAAD media campaign titled ‘A White Dress Doesn’t Cover the Rape’, which utilized various strategies, including public demonstrations, social media activism with the hashtag #Abolish522 and impactful visuals such as women wearing blood-stained wedding dresses to symbolize the injustice of the law – the article remained de facto active, as another provision in the law with the same effect remained, creating a legal loophole. Article 505 of the Lebanese Penal Code prohibits in fact sexual intercourse with a minor below the age of 18, yet it allows the perpetrator to escape punishment if he marries his victim if she is between 15 and 18 years of age, which circumvents other protections in the law against sexual violence against minors.

Banner of women’s right movement ABAAD media campaign titled ‘A White Dress Doesn’t Cover the Rape’, carried out in 2016 to abolish Article 522 of the Penal Code. Source: ABAAD

Despite most LAS countries having ratified UN human rights treaties such as CEDAW – committing themselves to upholding women’s rights with the adoption of gender-sensitive legal frameworks – the reality is that they all still fall short of international obligations. Equality Now’s report, acting as a blueprint for concrete and coordinated action, urges Arab countries – their governments, policymakers, legal practitioners, and civil society actors – to adopt a comprehensive consent-based definition of rape; to ensure laws meet international human rights standards and use gender-sensitive terminology; to ensure all non-consensual sexual acts are treated equally and seriously, regardless of gender, penetration type, or marital status; to remove legal and procedural requirements that make it burdensomely difficult to prove rape; to invest in healthcare, psychosocial services, legal aid, and confidential mechanisms for reporting gender-based violence; to train law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, and medical personnel in rights-based, gender-sensitive, survivor-centered approaches; to explicitly criminalize marital rape and repeal all legal provisions permitting impunity through marriage; and last to raise the age of marriage to 18 without exceptions.”

Focusing in particular on the last two points, Ayang stressed that “we cannot reform rape laws without addressing the issue of child marriage and marital rape. All these things are connected.” Marital rape, in fact, is not considered a crime in any of the LAS countries because in the context of marriage, at least in the monotheistic religions of Islam and Christianity, a woman is expected to grant sexual relations to her husband. “Many religious verses preach that this is a woman’s obligation,” she pointed out. “So when a woman says no in the context of marriage, that ‘no’ is not a recognized right. The context of consent within marriage, simply, does not exist.” Specifically in Jordan, Palestine (West Bank), and Syria, penal codes explicitly exclude the possibility of rape within marriage, the report reads. Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen go further by codifying in law a husband’s ‘right’ to sexual access, regardless of a wife’s consent. And the Lebanese law still maintains the spousal right to sex.

In relation to this, in the case of child marriage, legally a minor – whether married or not – cannot consent to sex because she is under 18, so child marriage automatically equates to marital rape, because a child cannot give consent. “That is why we say that there is a very strong connection between child marriage and marital rape. Countries that allow child marriage in their laws, for example in Palestine, set the minimum age for marriage at 18, but then provide for exceptions: a judge can allow girls aged 15 or 16 to marry. When child marriage is permitted on an exceptional basis, we say that it is marital rape: because the girl cannot give consent to marriage and therefore sex,” commented Ayang.

Moreover, rape within relationships of trust – whether between father and daughter, teacher and student, employer and employee, or religious leader and follower – amounts to a double crime: an act of violence and a betrayal of power. In such cases, the victim is cornered by dependency, authority, or vulnerability, making lenient penalties unconscionable. Children, people with disabilities, and those bound by trust are the easiest to silence: yet not a single Arab state has enacted a law that recognizes this full spectrum of abuse, where consent is stripped away by coercion disguised as authority.