In many countries, twenty-one marks the age of political maturity—the moment when a citizen is deemed fully capable of choice, accountability, and participation in shaping the public good. It is the age of agency, not guardianship.

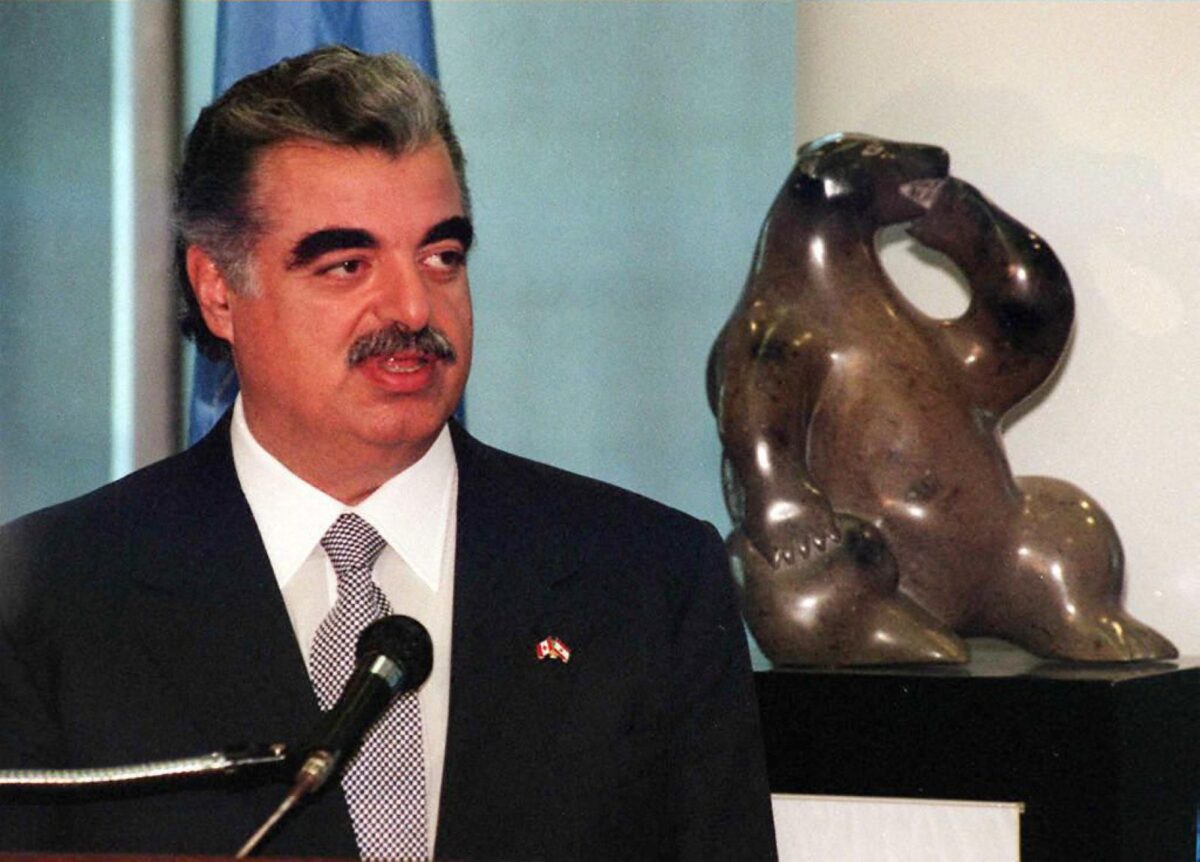

In Lebanon, however, the twenty-one years since the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri have traced the opposite trajectory. They have not been years of growth, but of managed spiral decline. What should have been a founding moment for a sovereign state became instead the slow-motion collapse of a political order that allowed Hariri’s killers to infiltrate the state, entrench themselves within it, and ultimately reshape it in their own nasty image.

On February 14, 2005, it was not only a man who was slayed. It was a possibility. The possibility that Lebanon could anchor itself in a project of statehood capable of breaking with the logic of militias and reconnecting the country to its Arab and international environment through economic integration rather than armed leverage. Hariri’s assassination was a blunt declaration that whoever holds the weapons retains a veto over the future.

The bitter irony is that the very system millions rallied to defend in Martyrs’ Square under the banner of sovereignty and independence would prove structurally incapable of defending itself. Lebanon did not fall in one dramatic rupture; it eroded through incremental concessions. It fell when weapons described as a “temporary exception” hardened into an unwritten constitutional constant. It fell when the logic of “compromise” superseded the logic of justice and accountability. It fell when the central political question shifted from “How do we end the phenomenon of arms outside the state?” to “How do we coexist with it?”

The entry of the assassins, Hezballah, into the state was not an accident of history. It was a methodical political process. From the moment indictments were issued to the systematic obstruction of the Special Tribunal, from the collapse of governments to the imposition of presidents, the formula remained consistent: surplus force yields surplus politics. What could have been a transitional justice moment—one that reasserted the primacy of law and institutional accountability—became instead the foundation of a new era of impunity.

Yet the responsibility does not rest on armed power alone. It also lies squarely with the political class that brandished the banner of sovereignty by day while negotiating accommodations with that same armed power by night. Parties that presented themselves as guardians of the constitution justified retreat in the name of “realism.” Leaders who spoke the language of confrontation before their constituents sat at the table of patronage to divide the state with those who had hollowed it out. Alliances born in moments of popular mobilization dissolved into cold arrangements designed not to restore the republic, but to preserve access to it.

Sovereignty became an electoral slogan rather than a governing program. The question of disarmament was endlessly deferred to “appropriate circumstances,” as though economic collapse, the Beirut port explosion, and the mass emigration of Lebanon’s youth did not already constitute sufficient evidence of systemic failure.

Twenty-one years after Hariri’s assassination, the question is no longer merely who killed him in operational terms. It is who enabled the trajectory that followed. Who accepted that the state would be managed through balance with a militia rather than through the monopoly of legitimate force. Who consented to a cabinet table that functioned as a negotiation arena between a state project and a sub-state project.

The most dangerous development over these two decades has not simply been the consolidation of armed power. It has been its normalization. Opposition to it became framed as recklessness; the demand that decisions of war and peace belong exclusively to the state was dismissed as a form of sovereign luxury. This normalization is the other face of the original crime, for it transforms exception into rule and fear into public policy.

If twenty-one is meant to be the age of accountability, Lebanon has failed that test. No architect, no executor, no enabler, and no broker of impunity has been meaningfully held to account. Instead of reckoning, there has been recycling. Instead of a renewed political contract, there has been reproduction of the same order with updated rhetoric and different faces but the same governing instinct.

Hariri, whether one agreed with all his policies or not, embodied the proposition that Lebanon could function as a normal state rather than as a message board for regional struggles. His assassination signaled that such normalcy was intolerable. The years that followed sent an even clearer message: that the system was prepared to adapt to the perpetrator rather than confront him.

Today, commemorating the anniversary cannot be reduced to replaying speeches or observing moments of silence. The real commemoration lies in revisiting the foundational question: Do we want a state that monopolizes the decision of war and peace, or a fragile entity suspended between armed balances and a rentier economy that oscillates between regional patronage and financial illusion?

Political maturity is not measured in years but in collective decisions. Lebanon remains politically underage because it has not yet dared to confront a basic truth: there is no sovereignty with arms outside the state; no justice built on compromises that override justice; no stability sustained by a political order that treats the state as spoils.

Perhaps it is time to transform this anniversary from ritual mourning into structural review—not only of those who detonated the bomb, but of those who provided cover, preferred transaction over confrontation, and cloaked accommodation in the language of prudence.

Twenty-one years is not a coming of age. It is a prolonged failure test. The question now is not how we remember February 14, 2005, but how we end the phase that began that day—a phase in which a political system chose coexistence with its assassins over the harder path of reclaiming the state.

This article originally appeared in Elaf

Makram Rabah is the managing editor at Now Lebanon and an Assistant Professor at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) covers collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He tweets at @makramrabah