Families of assassination victims say they learn to lean on each other for comfort while never expecting any justice for their slain loved ones.

On February 11, 2020, Ronnie Chatah, a young long-haired, blue-eyed man, stood at the grave of Lebanese writer and activist Lokman Slim in the Haret Hreik neighborhood in Beirut’s southern suburbs. Slim had been found dead with six bullets in his body the week before on a deserted rural road in South Lebanon. It was the first high-profile killing in Lebanon in years.

Ronnie’s father and former Finance Minister Mohammad Chatah was the last well-known Lebanese figure assassinated before Slim. In December 2013 a car bomb targeting Chatah detonated in central Beirut killing him and seven other people.

On Ronnie Chatah’s left stood Slim’s sister Rasha al-Ameer. On his right stood Malek Mroueh, whose father Kamel Mroueh, journalist and founder of the Lebanese English language newspaper the Daily Star, was killed in 1966 in his office.

“This is just one small group,” Chatah, 39, told NOW, recalling the gathering at Slim’s funeral.

“I should not know these people that well, and yet I do because we are all suffering together,” he stated solemnly. “This collective suffering is not what Lebanon should be about. It shouldn’t be shared trauma.”

Chatah keeps in touch with other relatives of assassination victims such as the niece of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri (killed in 2005) and the son of the former head of the Internal Security Forces Intelligence Service Wissam al-Hassan (killed in 2012).

Despite years of waiting, none of them have seen the results of the investigations into their family member’s murders. Slim’s death, like so many others before him, has become yet another political killing in Lebanon that the families will likely never see justice for, despite politicians promising thorough inquiries and international organizations calling for accountability.

‘A permanent scar’

It was a late December morning when a bomb took Chatah’s father away. Now, the 39-year-old host of the Beirut Banyan podcast has done his best to find some way to honor his father’s memory and heal himself and his family.

“It’s a horrible day and it’s a permanent scar,” he told NOW. “I hope that I found a way to honor his memory with either the podcast or my WalkBeirut tour.”

Chatah recognizes that this is not a unique story. Since Lebanon’s civil war, many people have been murdered for their political views with few, if any, of the families seeing any justice for their loved ones’ deaths.

“You have to learn how to live with it and, unfortunately, when you are in Lebanon, you live with it sometimes not just every day but hour by hour,” Chatah said.

When news of another killing reaches him, it reopens the old wounds of his father’s death and forces him to relive the moment he heard the news once again. This was the case when he learned of Slim’s killing.

“It sort of brings back a very familiar moment, albeit, it’s through someone else’s family,” he explained.

This is a feeling that Giselle Khoury, the 60-year-old founder of the Samir Kassir Foundation, knows all too well. Her husband, Samir Kassir, was killed by a bomb that was placed under his car in the Achrafieh neighborhood of Beirut on June 2, 2005.

For Khoury, the similarities between what both Slim and Kassir stood for are a brutal reminder of the cost that their work can sometimes demand.

“Lokman’s assassination reminded me of the first days of Samir’s assassination. It’s another Samir,” she told NOW.

While he has made peace with his father’s death the best that he can, Chatah is often reminded that he will never see the perpetrator of the assassination brought to justice, just like all of the others.

International justice takes a long time

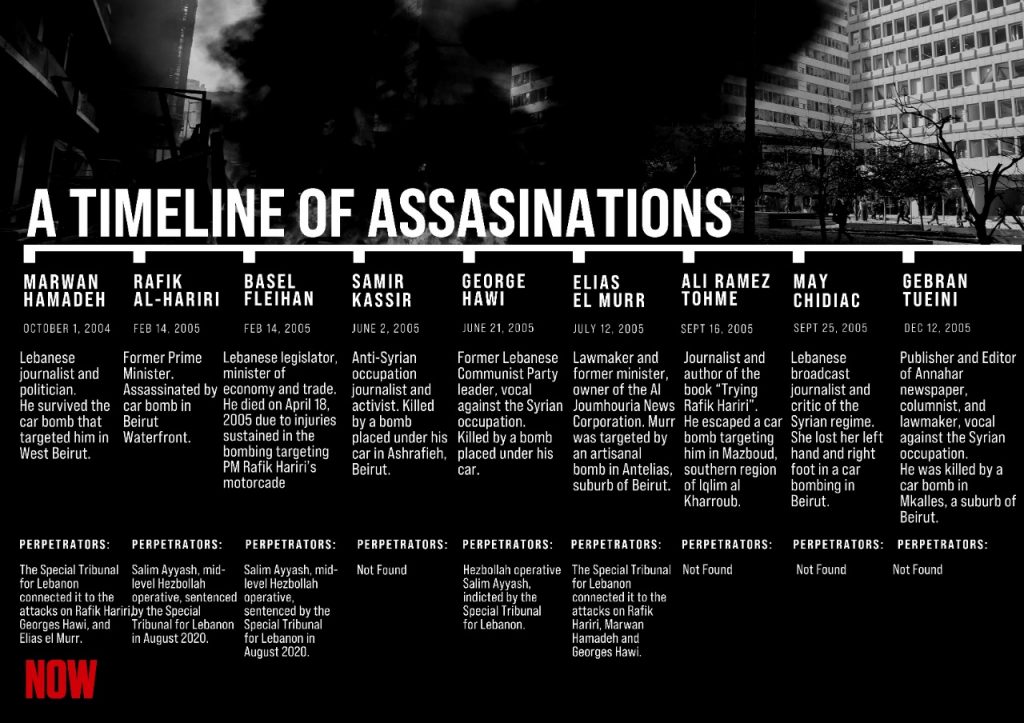

On Valentine’s Day 2005, former prime minister Rafik Hariri was killed in an explosion that shook the Lebanese capital.

In the years following the assassination, the United Nations set up the Special Tribunal for Lebanon with the sole purpose of investigating and prosecuting those responsible for murdering the former prime minister and nearly two dozen others.

After Kassir was assassinated, Khoury demanded that his case be investigated by French authorities since her late husband had dual nationality, French and Lebanese.

That investigation never happened and she eventually had his case tried alongside Hariri’s at the Tribunal.

Over the 15 years that it took for the investigation to conclude and for the tribunal to pass a sentence, there were a dozen more high-profile assassinations and assassination attempts. None of these killings saw any perpetrators identified.

When the tribunal finally issued its verdict, one mid-level Hezbollah operative, Salim Ayyash, was found guilty.

“We accept the court’s ruling and want justice to be served so that the criminals are clearly brought to justice,” Rafik’s son Saad Hariri said following the announcement of the verdict on August 18, 2020.

Not everyone, though, was satisfied with the ruling.

Khoury said that just finding Ayyash guilty was “not enough” and was critical of the limitations that the court has, specifically that a dead person cannot be prosecuted. Hezbollah high-ranking commanders Imad Mughnieyh and Mustafa Badredinne, who had been named in the indictment as allegedly involved in Hariri’s killing, were both killed in Syria in 2008, respectively 2016, and could never be officially indicted.

“I think it’s a big mistake and it’s a handicap to having the truth. It’s disappointing. I need more. It’s nothing Ayyash. I really need more.”

Nearly a year later, Ayyash is still a free man. But that has not deterred Hariri from continuing to demand justice for his father.

On the 16 year anniversary of the assassination, he continued to call for the tribunal’s verdict to be upheld and Ayyash arrested.

“A judgment was issued by the Special Court for Lebanon against Salim Ayyash, one of the assassins of the late prime minister,” Hariri demanded. “This ruling must be implemented, and Ayyash must be delivered, no matter how long it takes”

Hezbollah has continued to view the tribunal as illegitimate and has refused to hand over Ayyash, making it highly unlikely that the Hezbollah operative will serve any time in prison.

While Chatah agreed that Ayyash would most likely avoid any jail time, he argued that the thousand-page report does provide a sense of closure for the infamous killing by acknowledging the guilty party.

“There’s a conclusion which is that there is a responsible actor in this country that committed at least that crime and the attempted ones that are referred to in the Tribunal’s document,” Chatah said.

“That said, you would want to see the criminal arrested and serving time,” he later added. “That did not happen.”

This is still more than what most families of the victims of political assassinations get.

A culture of impunity

Ever since the warlords of the civil war were granted general amnesty in 1990, a precedent for impunity in Lebanon was set in motion. This has allowed corruption, allegations of torture and assassinations to go uninvestigated.

“In the peace period after the war, especially after 2005, we witnessed a series of assassinations of MPs, journalists, intellectuals who were opposed to the Syrian regime’s presence in Lebanon,” Sahar Mandour, the Lebanon researcher for Amnesty International, told NOW. “Their assassinations were never investigated. There’s always the announcement of an investigation and, then, we never get a result out of it. Effectively, after the war, the impunity continued.”

To compound this culture of impunity, during the appointment of new judges, the various parties will often fight amongst themselves over how many seats each party gets, making it a long and drawn-out process that the public can only watch.

“The speaker of the parliament wants a share, Hariri wants a share, then the president wants a third share, then there’s the fight around the shares,” Mandour said. “These are not feuds that happen in private and we’re speculating around them.”

The judges appointed are usually affiliated with a specific party or politician and are, for the most part, not chosen on their abilities as a judge, but how they can advance the interests of a certain party.

Politicians are also more than happy to protect each other. When outgoing PM Hassan Diab, former Minister of Finance Ali Hassan Khalil and former ministers of public works Yousef Finianous and Ghazi Zaiter were called in for questioning by the previous investigator of the Beirut Port explosion Fadi Sawan, they outright refused, putting them at risk of arrest if a warrant was issued for their unwillingness to comply.

However, the outgoing interior minister, Mohammed Fahmi said that he would not send security forces to enforce this warrant and even challenged the judiciary to come after him as well.

“I would not order the security agencies to implement such a legal decision, and let them pursue me if they wish,” Fahmi stated firmly.

Few in Lebanon have hope that any recent assassinations will be properly investigated. In the hours after Lokman Slim’s death was announced, there was an outpouring of distrust that there would be any serious investigation into the murder.

“These law enforcement agencies have received billions from France, Germany, the US, and the UK to purchase state of art equipment, they have been trained by them,” Ayman Mhanna, Executive Director of the Beirut-based Samir Kassir Foundation, a freedom of expression NGO covering the Levant region, stated pessimistically during an interview with Al-Jazeera at Slim’s funeral. “For what? Is the equipment only to be used against protesters, as a report by Amnesty International said, or to spy on journalists? This is the question for western parliamentarians to ask and find out what is done with their taxpayers’ money.”

Mandour also expressed doubt that there would be any justice for Slim due to the close ties that the judiciary has to the ruling political elite.

“It’s not the first assassination in the country and it won’t be the last, but no one was held accountable for all of these assassinations,” she said. “There’s a general understanding among the population that accountability is hard to reach within this judiciary system that is inherently tied to the executive authority and the political regime.”

After Kassir was killed, Khoury said that she had little faith in the Lebanese judiciary to properly investigate and hold accountable his assailants.

“Concerning the Lebanese justice, there is nothing,” she stated bluntly. “I can’t talk about the Lebanese judges. I don’t trust them. I don’t think that they did their job.”

According to Mandour, politicians will call for an investigation and for justice, but, as soon as it starts to affect them, they will condemn and label the investigation as being sectarian and politicizing events. The researcher added that this was a common tactic used to perpetuate impunity in Lebanon and is used in all sorts of scenarios whether it is an assassination, the investigation into the Beirut Port explosion or the right for women to pass on her nationality to her family.

“You can find it everywhere,” she said jokingly. “It’s the Panadol of excuses. Whatever you feel, you can take it and it will help.”

Since it is nearly impossible to hold anyone to account, families of the victims of assassinations have had to find other ways to hold people to account.

A different type of justice

Chatah knows that his father’s killers will never be held accountable. Because of that, he has tried to find poetic justice, something that he describes as “preserving truth over fiction and delivering the truth the way a citizen can.”

“It’s an individual or individuals with a voice,” he explained. “Literally something like a eulogy. That’s a form of poetic justice. It could be a podcast repeatedly recognizing the truth. It could be writing. It could be journalism.”

For Chatah, keeping his father’s ideas alive through his podcast allows him to honor his memory as well as find some semblance of justice. It also makes sure that his assassination is never forgotten and, according to Chatah, helps to keep the pressure on his killer.

“It also gives me the knowledge, the firm ability to know for a fact that his killers are not comfortable,” Chatah stated. “His killers aren’t living a life of freedom and luxury. They’re on the run all the time and there are enough people that firmly believe that those people should be held to account.”

All of this, Chatah says, “helps me retain my sanity.”

Khoury has also found some solace in her work at the Samir Kassir Foundation which she describes as her “baby with Samir.” While she may never see justice for his death, it allows her to continue his legacy and views it as a way of getting revenge against his killers.

“I’m trying and this is my struggle and this is my cause,” Khoury said passionately. “We are here and we will stay here even if you are under threat or even if they kill us. But we are here and we resist.”

If not for a sectarian judiciary, carefully selected by party leaders, change would not be so hard to come by.

Mandour says that the Parliament does have in its drawers bills that would create an independent judiciary and could help to restore people’s trust in the judicial system. However, these laws have a low likelihood of passing given the current parties that are in power.

“The judicial system was tailored in this way in order to protect impunity and block accountability,” she said. “Until there’s a change in will or in people, change in the political scene in Lebanon, change of authority, change of perspective, change of approach, there’s no way.”

Nicholas Frakes is a multimedia reporter with @NOW_leb. He tweets @nicfrakesjourno.

Graphics by Tala Ramadan. She is on Twitter @TalaRamadan.