Omar Fattouh lives to keep his trade, which he founded over 40 years ago, before the Lebanese civil war, running.

“See this business?” Fattouh, 74, asked as he sipped his morning Turkish coffee sitting on an antique woven chair in the middle of his store packed with apparel, footwear and accessories. “I made this by myself. This business survived a war and two currency crashes.”

Not long ago, Lebanon was dubbed the “Switzerland of the Middle East”, with Beirut as its “Paris” due to its financial stability in the mid-20th century and its flourishing tourism.

The 1975-1990s civil war quickly came and deflated that balloon and today, the country is a failed state with an economy that made headway to hit one of the most severe crises episodes globally since the mid-19th century, a blistering reality.

The switch from financial stability to sheer collapse was a gruesome transition, but it was not an overnight shift the way it exhibited itself on the ground. Analysts say the mercurial economic model adopted post-war in the 1990s, rendered as successful at the time, had lethal and deep-rooted implications for the small Mediterranean country and paved the way to today’s inevitable crisis.

History is NOT repeating itself

“I kept my money in Lebanese lira in the bank and I was confident in my strategy,” Fattouh said. “I never thought, for a second, the currency was about to crumble back then.”

When referring to the 1975-1990 civil war, many of the older citizens, who survived that bleak period and the war-ravaged economy, tend to focus principally on conflict anecdotes and barely mention anything about an economic turmoil. They dwell on the fact that today’s crisis is more calamitous.

The state did not collapse until later stages in the conflict, around 1983, when capitals departed and the Lebanese lira foundered. One US dollar was worth 4.5 Lebanese lira in 1982 and 500 in 1988, which depleted people’s savings, minimized their purchasing power, and stripped Fattouh’s savings from him.

But several things were distinctive from today’s crisis.

“The banks were in a very good shape back then,” said Mike Azar, an expert on the Lebanese financial system. “The banking system was very liquid, flush with dollars, and a great deal of money was flowing into the country at that time. We imported way less as we still had something of an economy and the demand for dollars was much lower.”

Thanks to accumulated reserves during that period and low public debt, the economy and the currency managed to survive during the war’s onset, and a banking sector collapse was avoided.

“Dollar deposits at that time remained untouched and many Lebanese people kept their money in US dollars, a few who kept their money in lira lost its value,” said Danielle Hatem, a financial advisor.

The end of the “Lebanese Miracle”

Since its establishment in 1920 under the French mandate, Lebanon has been distinguished as an economic miracle that conveys it as an epitome of economic success in the Middle East. The civil war and the socioeconomic struggles of that time soon stripped the country of its reputation.

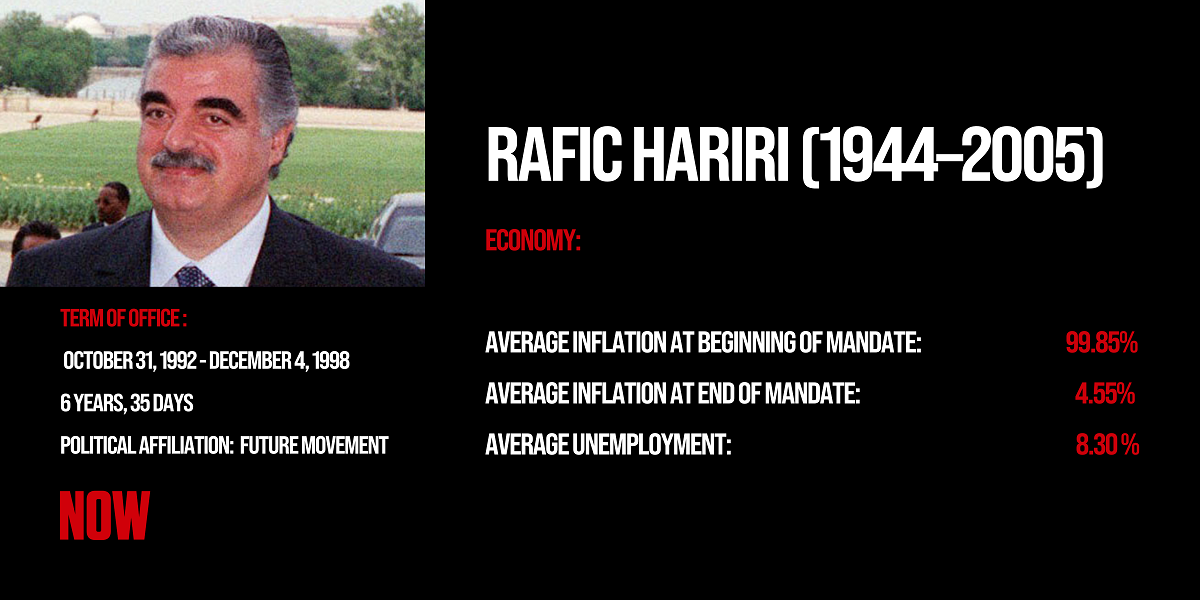

From 1992 to 2004, Rafik Hariri, an extremely wealthy businessman, who rose to power alongside pardoned warlords, was at the center of Lebanon’s post-war history. He spearheaded the national effort to “reconstruct post-war Lebanon” and restructure its shattered economy, along with Saudi and western backing. Hariri strived to privatize the corrupt state sector and attract foreign capital.

He succeeded, owing to his deep pockets and international relations, in restoring a critical condition to economic recovery, one that seems far-fetched today, which is confidence in the economy.

“A political figure came in, who represented confidence back then and brought with him money from the Arab countries,” Hatem said. “An economic growth occurred, the exchange rate was fixed and infrastructure developments emerged, perhaps at the expense of some people, but the economy was generally recovering.”

To achieve “National Consensus” post-war, public expenses were masterly dispensed among confessional factions, who distributed state assets and institutions amongst themselves. Such institutions were the Council for Development and Reconstruction, the Fund for the Displaced, and the South Fund, all of which offered the ruling warlords an opportunity to invest in reconstructing the war-scarred country and ultimately amass political and financial profits.

Hariri eventually disclosed that the nation “bought civil peace”.

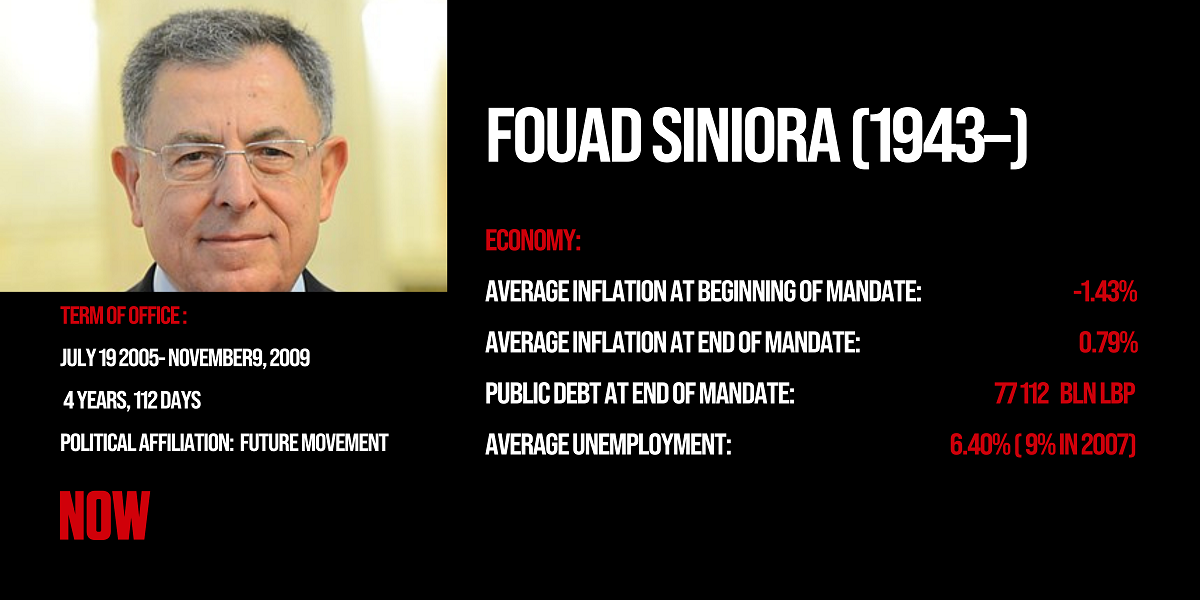

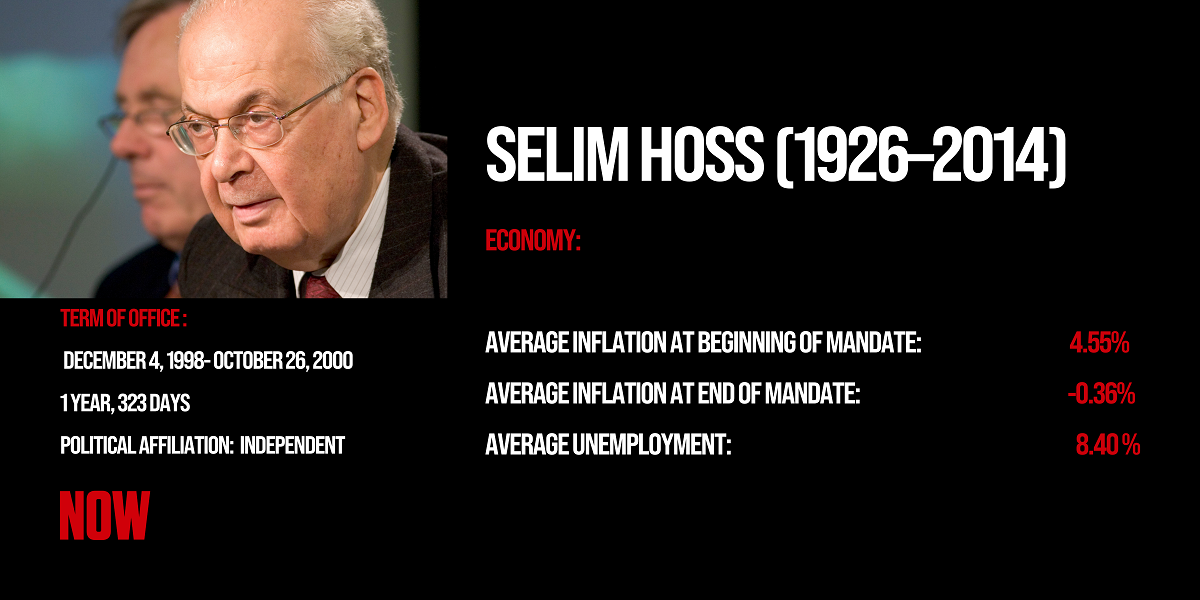

Driven to attract capital, Lebanon’s central bank, Banque du Liban (BdL), stabilized the currency and pegged it to the US dollar at a rate of 1507.5 to 1 which in turn curbed the soaring inflation rate and lowered it from 99.85 percent in 1992 to 4.55 percent in 1998. This motivation was closely tied to the government’s rule to tap into international capital markets.

According to Azar, the peg should’ve been temporary, but the government carried on financing it until it became progressively expensive.

Today, with a record triple-digit year-on-year inflation rate, further expanding the already-large public debt is no longer an option to the bankrupt state as its debt has totaled more than 170 percent of GDP, one of the highest rates in the world.

The unsustainable and controversial economic model engineered in the 1990s was vulnerable to external and regional shocks. According to Mohammad Zbeeb, an economic journalist, this model had the potential to explode several times during the last two decades but “external interferences bought us more time.”

However, geopolitics is altered now. Western powers have little interest in aiding Lebanon, and a diplomatic row has seen Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries drop much-needed financial and political assistance for Lebanon due to Iran-backed Hezbollah’s growing influence in the country. The dispute reached a pinnacle when a recent media statement by Lebanon’s previous minister of Information, George Kurdahi, described the Yemen war as “futile and pointless” and that Houthis were “defending themselves against an external aggression”.

A convoluted plight

The Lebanese government, throughout the years, has been spending beyond its income, characterized as a fiscal deficit, and the value of goods and services the nation imports exceeds that of which it exports, characterized as a current account deficit or trade deficit. Having both ultimately translates to the term known as Twin Deficit, explains Zbeeb.

“Lebanon had to finance these two deficits,” he said. “Internal debt to finance the fiscal deficit and foreign debt to finance the trade deficit.”

During the civil war, an estimated 894,717 people, nearly a third of the country’s population, fled strife-torn Lebanon. This migration generated remittances in hard currency.

“The migration of the Lebanese workforce provided an opportunity to elongate the survival of this economic model.”

This resulted in a lopsided economy that gratified the service industry and real estate market to the detriment of the manufacturing industry, which had already taken a major hit during the war.

When Fattouh had started his clothing business, he owned a shop in Sursock Souks and another in downtown Beirut. “Before everything was wiped out during “Al-ahdath”.”

Al-ahdath is Arabic for “the events”, a term broadly used to refer to the civil war clashes.

Fattouh, whose money lost its value due to the current economic crisis and his other dollar savings are trapped in the banks, used to manufacture his merchandise but later started relying on imports from Syria and Turkey. “I saved this money for my final days and to keep this business alive, now it’s all gone.”

Another economic term to describe Lebanon’s crisis is the Dutch Disease, said Zbeeb. It is a syndrome widely attributed to the adverse effects of a sharp surge in a country’s income which the Netherlands witnessed during the 1960s after finding substantial natural gas deposits in the North Sea. A dramatic rise in the country’s wealth, a seemingly constructive event, paradoxically, left behind bleak outcomes on important economic sectors and made Dutch non-oil exports overpriced and, consequently, less competitive.

While Dutch Disease commonly corresponds to resource-rich commodity countries or a natural resource discovery, it can manifest itself as a consequence of any occurrence that catalyzes a massive influx of foreign currency, exactly what happened in Lebanon in the 1990s. Questionable financial engineering by BdL saw large sums of foreign currency inflow characterized by foreign debt, foreign direct investment (attracted by high-interest rates) and the diaspora’s remittances.

“Through which government expenditure was financed and consequently lead to expand our export demands and dwindle our local production,” Zbeeb added.

A "Zombie Economy"

Despite the fact that today’s crisis is fundamentally distinctive from the country’s lira crash during the civil war, the lack of political will among the ruling class to redeem the cash-strapped economy and provide a tenable and fair alternative is what remains constant.

Lebanon’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) experienced a 58 percent contraction in 2021 compared to 2019, the largest among 193 countries examined by the World Bank.

The Lebanese pound has lost over 90 percent of its value since 2019 and is currently trading at around 21,200 to $1. BdL’s Governor, Riad Salameh has been pumping millions of dollars of the bank’s dwindling foreign reserves into the currency market with an eye toward lira appreciation. Many experts believe such attempts are toothless and unavailing in the long term.

The 2022 draft budget, released on January 21, foresees a 20.8 percent deficit for the debt-ridden country in the upcoming fiscal year.

“Nothing serious has been done by the government till this day,” Hatem said. “Usually a full financial plan is designed before the draft budget, it is merely an effort to gain popularity ahead of the elections.”

“Lebanon’s [economic] model has become a zombie,” Zbeeb said. “To imagine its continuity for a long time without any changes is to imagine a miserable and poverty-stricken society.”

He hinges Lebanon’s recovery on a complete change in the current model, a lower dependence on remittances, and the evolution of an economic model and political system that allows a productive industry to thrive and lessens import demands.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has rejected the government’s financial plan that heaps the lion’s share of financial losses on depositors rather than bank shareholders. The country is hoping to strike a vital bailout deal with the IMF, but a plan for restructuring Lebanon’s banking sector needs to be approved first.

Azar believes that the Lebanese currency is no longer “viable”.

The quest to restore confidence and convince people to keep their savings in lira again is implausible. “There's been far too much damage,” he said.

“The options left for Lebanon are full dollarization of the economy, which is basically what is already happening,” Azar said. “I think that's a real possible outcome, whether voluntarily or by force.”

“Would you put your life savings in lira in a Lebanese bank if the government "did restructuring" and told you everything is fine now?”

Sally Abou AlJoud is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_Leb. She is on Twitter @JoudSally.