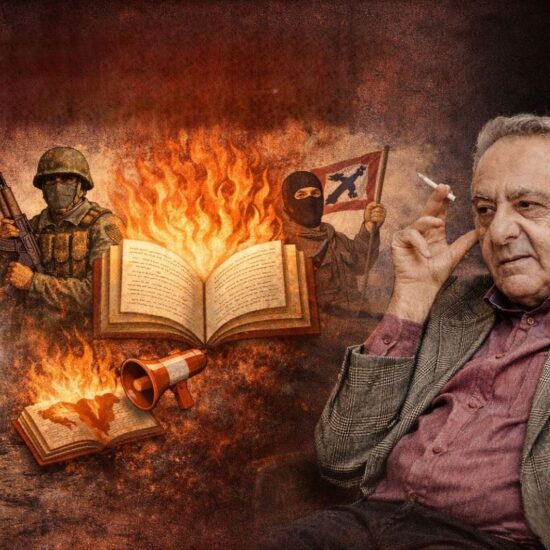

Amid Syria’s escalating sectarian violence, many in Lebanon fear the conflict could spill over, further destabilizing a country already grappling with internal tensions and regional threats

Jana Abi Nader spends her days glued to the TV or her phone, closely following the news from Syria. This wasn’t part of her routine before—Lebanon has more than enough news of its own—but recent developments have left her fearing that her city, Tripoli, could erupt in violence at any moment.

“We knew there would be sectarian tensions after the [Assad] regime fell,” Abi Nader told NOW. “We just didn’t know if we would be affected.”

According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, around 800 people have been killed in Syria in five days, most of whom were Alawites. The surge in sectarian violence follows clashes between pro-government forces and armed opposition groups, which Damascus claims are loyal to former President Bashar Al Assad.

Tripoli, in northern Lebanon, is a Sunni-majority city but also home to Christian and Shia minorities. It has long been a place of religious diversity, history and culture. However, its proximity to Syria deeply worries Abi Nader, who believes Lebanon is directly affected by the conflict. The situation feels even more precarious as Lebanon still grapples with Israeli forces occupying parts of its southern border and daily ceasefire breaches.

The sectarian strife in Syria has reignited fears of similar tensions in Lebanon, a country that endured a devastating 15-year civil war and has only just emerged from a 66-day war with Israel.

“We are tired of living like this,” Abi Nader said.

What’s happening in Syria?

Violence erupted in Syria’s coastal region last week, where a large Alawite population resides, after the Sunni Islamist-led government reported an attack by remnants of the former Assad regime. Armed groups quickly gained control of Qardaha, prompting government forces to deploy reinforcements and launch airstrikes to reclaim territory. However, the situation escalated further as gunmen spread across Latakia and Tartus, raiding homes, looting businesses, and targeting Alawi communities in a series of brutal sectarian massacres.

Amid growing fear, threats circulated on social media, warning residents that attacks would take place during Suhoor, the pre-dawn meal in Ramadan. This led to a mass exodus, with thousands fleeing to Lebanon, particularly to the northern Akkar region. Lebanese authorities reported that over 1,400 families—totaling more than 6,000 people—had arrived in Akkar in recent days. In total, approximately 10,000 Alawites have sought refuge in Lebanon, primarily settling in Tripoli and its surroundings.

The influx of refugees has intensified existing sectarian tensions in Lebanon, particularly in Tripoli, a city historically divided between Sunni-majority Bab Al Tebbaneh, which supports the Syrian uprising, and Alawite-majority Jabal Mohsen, which remains loyal to the former Assad regime. Security forces have established a perimeter around Jabal Mohsen to contain potential violence, but confrontations have already taken place, leaving the situation fragile. Meanwhile, Sunni militant groups from Lebanon have also been sending fighters across the border to support Syrian rebel factions, further complicating the crisis.

In response to the violence, Syria’s interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa vowed to hold all perpetrators accountable, even within his own ranks. He also acknowledged that both Syrian and foreign militants were involved in the attacks and that some armed groups had ordered women to leave villages before claiming the land as their own.

What now for Lebanon?

Lama Hamza, a Syrian citizen currently residing in Beirut, worries that rising fears about Syrians could lead to violence against them.

“We obviously don’t mean harm to anyone and do not condone the violence happening in Syria, but sometimes people start hating you just for being Syrian,” Hamza told NOW.

Lebanon hosts the highest number of refugees per capita and per square kilometer in the world, with government estimates putting the number of Syrian refugees at 1.5 million, alongside some 11,238 refugees of other nationalities. The country also has a history of discrimination against Syrians.

“We’ve been in Lebanon for over a decade, living peacefully with our neighbors, and we hope that doesn’t change,” she said.

However, Hamza has noticed a surge in social media posts calling for Syrians to be expelled or for people to arm themselves in case of an attack.

“It’s not like we’re hiding weapons in our houses, waiting for the right moment to start shooting everyone,” she said with a nervous laugh. “Our country has already suffered enough violence and strife—we just want both countries to live in peace.”

A mother of three, Hamza has long lived with the fear of being forced to leave Lebanon. For her, the country remains the best place for her children to grow up and build a future.

Abi Nader is torn between staying in Tripoli or leaving. While she has not witnessed any violence yet and does not want to live in constant fear, she wonders if opposition groups will target Alawite villages in Lebanon next, leading to a rapid escalation of violence.

“No one wants to leave their home, and where would we go anyway?” Abi Nader said. Now as she goes to work or to stroll the streets, she says there is an obvious fear in people’s eyes when they talk about what’s happening in Syria.

As tensions rise in the region, Abi Nader’s uncertainty mirrors the growing fear in Lebanon. With the spillover of violence from Syria, many, like her, are left to wonder if the calm they’ve known in their communities will soon give way to sectarian conflict. In a country already scarred by a long history of internal strife, the specter of violence feels ever-present. The possibility of Lebanon becoming the next battleground is not just a distant worry but a very real concern for those living on its fragile borders. For now, people like Abi Nader hold their breath, hoping for peace but bracing for the worst as the fragile stability of Lebanon hangs in the balance.