The year 1958 was a year of turmoil in Lebanon. The term of its president, Camille Chamoun, was coming to an end with no clear successor in sight.

Chamoun, the second president of the Republic of Lebanon post-independence from France, was elected for a six-year term in 1952, a term that under the constitution could not be renewed or extended. He was accused by his opponents of rigging the parliamentary elections of 1957 in order to amend the constitution so he could become eligible for a second term, an accusation he never accepted. Nevertheless, this led to a mini-civil war and bloody conflicts in 1958.

Lebanon at the time was caught in a tug of war between the West, led by the USA and favored by Chamoun; and the East, led by the Soviet Union and represented by many of its allies in the Middle East, including Lebanon. Prime among them was President Gamal Abdul Nasser of Egypt. The conflict in Lebanon dragged on indecisively for a few months until a bloody coup d’état in Iraq on July 14 deposed the pro-western monarchy in favor of a Nasserite military regime.

This is when President Eisenhower, fearing a power shift in the region, sent the US Sixth Fleet to the shores of Lebanon carrying 5,000 marines who stormed the beaches south of Beirut on July 15, 1958. As a thirteen-year-old, I was passing the time on a slow summer afternoon with a cousin, playing backgammon on his balcony with a direct line of sight to the landing operation. We were approximately two miles away and had the advantage of being on a hill several hundred feet higher than the landing theater.

The commander of the American Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean Sea was Admiral George Whelan Anderson, Jr. (1).

My cousin and I watched the elaborate landing maneuvers, with one craft after another being lowered into the Mediterranean and navigating in circles around the ships. Then, suddenly, all the craft headed towards the golden sands of the beach landing zone where hundreds of marines disembarked in unison. As the soldiers later would tell, they were expecting a Normandy-style invasion with bloody combat operations, only to be met with peddlers trying to sell them cigarettes, soft drinks, chewing gum, and trinkets.

The landing succeeded in quelling whatever military conflict was taking place amongst the Lebanese. This was in recognition of the might of their arriving guests. The attention soon turned to a political process led by the Americans to solve Lebanon’s governance problems.

The marines were shortly followed by units of the US Army which counted one Private Elvis Presley amongst it ranks; rumors in Lebanon had the American rockabilly star amongst the expected arriving soldiers, but it never came to pass.

My hometown of Choueifat, with a population between seven and 10 thousand inhabitants at the time, was for centuries blessed with a coastal plain that featured one of the largest continuous olive groves in the world. The olive trees, estimated to be over eight hundred years old, were of exceptional Mediterranean quality and a source of pride and livelihood for the town’s folks. Unfortunately, starting late in the 20th century, “modern development” destroyed almost all of them. In 1958 however, these groves made for an ideal encampment for the US troops. Most of the property owners lived in the hills above and away from them so initially, there were no homes or residents to interact with.

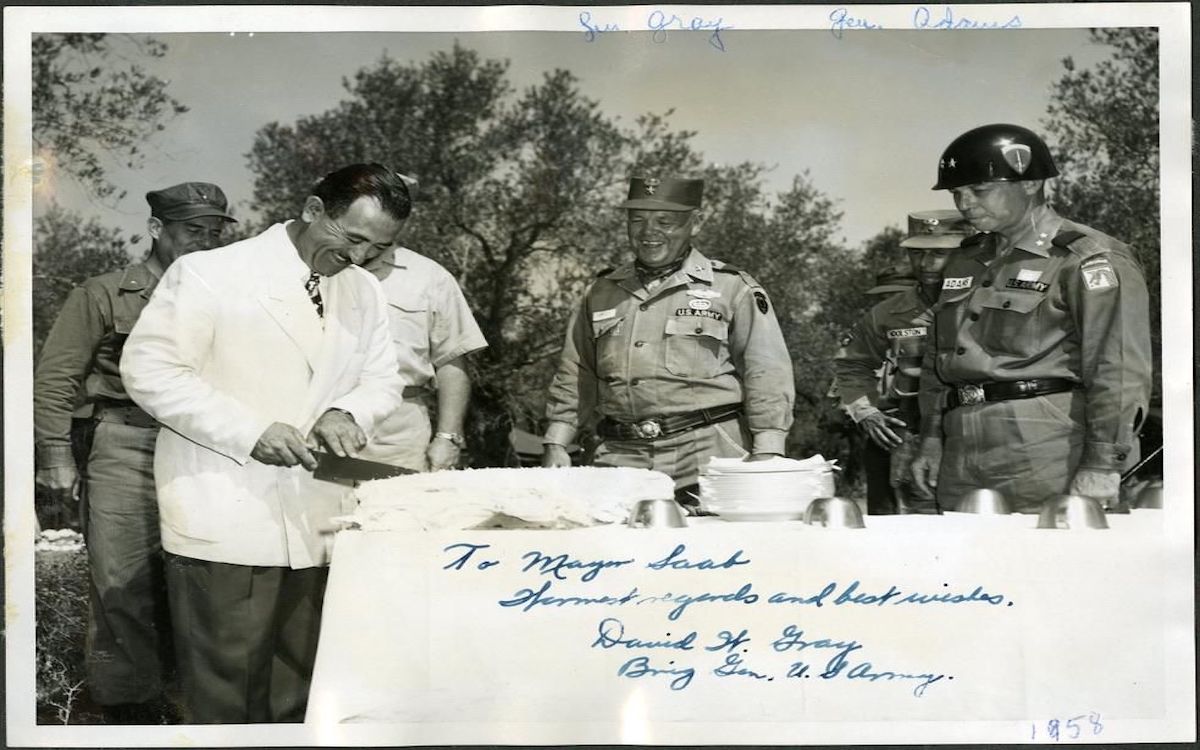

My father, Mahmoud K. Saab, was the mayor of Choueifat at that time. It was natural for the US Army to establish a working relationship with the local authority in order to ensure smooth and friendly interactions between the visitors and the local population.

For starters, an army delegation requested an introductory meeting with the mayor, which was readily granted. In order to ensure a productive meeting, the American Army found amongst its ranks a colonel by the name of Shehab (2) who was of Lebanese ancestry and who knew some Arabic. He was asked to act as a translator for the meeting. Colonel Shehab arrived thirty minutes ahead of the delegation in order to get acquainted with the mayor and to practice his Arabic, which he had rarely used since childhood.

Upon the Americans’ arrival, Colonel Shehab stood up and introduced my father as follows: I would like you to meet mayor Saab who not only speaks better Arabic than I do; he also speaks better English than I do. My father held an undergraduate and a graduate degree from the American University of Beirut and was an executive of an American Oil Company. This introduction set a tone of good humor, congeniality and cooperation that marked the relationship between the US Army and the town of Choueifat the entire time the Army was on the ground there.

It would be an understatement to say that life in Choueifat for the three or four months when the US Army was there was not the same. Army vehicles represented a huge increase in traffic on the streets, there were even traffic accidents involving US Army vehicles exclusively. Commercial interactions between townsfolk and visitors were many, and everyone was abuzz about what the visitors were up to and how they passed their time. Many of my cousins and friends perfected their poker games by learning from the GIs. The locals enhanced their English vocabulary with a collection of four-letter words they did not know existed. The restaurants and cafes loaded up their jukeboxes with popular American music of the time.

One of the most memorable and unusual incidents for Choueifat was when the townsfolk looked up to the sky one day and saw a US army helicopter flying overhead with a donkey suspended from it. What had happened was that the army had purchased beasts of burden to help with transportation in areas not accessible by motorized vehicles. The lucky donkey was by the seashore when its handlers decided it was more needed at the mountain top, so a truck was brought and prepared for the donkey to be loaded in the back. But the donkey, known for stubbornness, refused to move. The next best solution was to put a couple of straps under the animal’s belly and hook them up to the helicopter.

To its credit, when the US Army left the Olive Groves of Choueifat, it undertook, in cooperation with the municipality, a study to evaluate any damage it may have inflicted on the trees. Joint teams of assessors surveyed the area and presented a report that was the basis for generous compensation to the farmers. My father asked me to act as a translator on one such team, which consisted of a member of the municipality council by the name of Nassib and a US Army Second Lieutenant. Nassib and the Lieutenant did not get along at all; not only could they not agree on what was damaged, but even had a hard time deciding which route to take to cover their designated area. My job evolved from translator to peacemaker; fortunately, both sides liked me, so they were able to successfully accomplish the task at hand.

This brings me to another memorable – for me at least – incident associated with the presence of the US forces in Lebanon in 1958.

Summertime in Lebanon for my family, friends and many Lebanese was the time to enjoy the cool waters and the beautiful sandy beaches of the Mediterranean Sea. We made the short trip almost daily, mostly with the same friends who shared a love for the beach.

One such afternoon, with a perfectly calm sea and beautiful blue skies, I was in the water near one of my dad’s friends with dozens of other swimmers around us. Towards the west, a great big ship stood still in the water, within what we thought was easy swimming distance from us, not realizing at the time that an aircraft carrier several miles out to sea will look like a short swim away. Fouad, in his early forties, and I, thirteen years of age, decided to swim to the ship. We told no one because we thought we’d be back in no time.

We swam and swam and then swam. The further we went the greater our sense of accomplishment. Although we were both good swimmers, we were ill-prepared for long-distance swimming and had to take breaks; we carried absolutely no safety equipment such as life jackets or floatation devices. The further we went, the prouder of ourselves we became, and the more determined to make it to the ship. After all, knowing how friendly the Americans were, the least we expected was that we’ll be treated to good American hospitality and delivered back to shore in a speed boat.

After hours of swimming, we must have gotten close enough to the ship to be detected by its sentries, a helicopter came from the carrier and circled above us, we could clearly see the pilot, our eyes met, we waved at him and he waved back, and then went back to his ship. This is when we began to doubt that we will be welcomed by Admiral Anderson (we did not know his name at the time).

Before we had time to evaluate our predicament, my father, paddling a board, reached us with the angriest look I had ever seen on his face. His hand was bleeding from a cut caused by a nail in the wooden paddle. He never looked at his friend, he just motioned for me to get on top of the small board, which we did. Before long, a rowboat with fishermen heading to shore was about to overtake us when they saw and recognized my dad and came to our aid. We boarded their small craft and headed to shore. Along the way, dozens of other swimmers who must have tried to follow us were asking for a lift back to shore; alas the boat was already overloaded, and they were not far enough to be in real peril.

To this day, this story stands out as one of my most egregious youthful indiscretions; I never appreciated what my father must have gone through until I became a father myself. My only excuse is that I thought I had adult supervision. It seems age alone does not an adult make.

- As a flag officer, Anderson commanded Task Force 77 between Taiwan and Mainland China, Carrier Division 6, in the Mediterranean during the 1958 Lebanon landing and, as a vice admiral, commanded the United States Sixth Fleet. As Chief of Naval Operations in charge of the US quarantine of Cuba during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, Anderson distinguished himself in the Navy’s conduct of those operations. Time magazine featured him on the cover[1] and called him “an aggressive blue-water sailor of unfaltering competence and uncommon flair.” He had, however, a contentious relationship with Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. At one point during the crisis, Anderson ordered McNamara out of the Pentagon’s Flag Plot when the Secretary inquired as to the Navy’s intended procedures for stopping Soviet submarines;[2]McNamara viewed those actions as mutinous and forced Anderson to retire in 1963. Many senior naval officers had believed Anderson’s next appointment would have been to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

- Lieutenant Colonel Alfred H.M. Shehab was commissioned as a Cavalry Officer upon graduation from Officer Candidate School, Fort Knox, Kentucky, Class 9-42, 22 August 1942. His first duty assignment was as Platoon Leader, Reconnaissance Company, 37th Armored Regiment, 4th Armored Division, Pine Camp, New York. | His subsequent duty assignments include: Instructor Tactical Officer, Military Intelligence Training Center, Camp Ritchie, Maryland; Troop Commander, Headquarters and Service Troop, 23rd Infantry Cavalry Reconnaissance Squad, 16th AD, Camp Chaffee, Arkansas; Acting S-2, Headquarters, 11th Cavalry Group, Camp Gordon, Georgia; Reconnaissance Officer, Troop B, 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squad, European Theater of Operations; Troop Commander, Troop B, 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squad, European Theater of Operations; Troop Executive Commander, Troop B, 38th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squad, Losey Field, Puerto Rico; Student Officer, Counter Intelligence Center, Camp Holabird, Maryland; Student Officer, Army Language School, Presidio of Monterey, California; Counter Intelligence Officer, 108th CIC, White Plains, New York; Armor Advisor, 8688th AAU, Saudi Arabia; Translations Officer, 525th Military Intelligence Group, Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Assistant G-1, 4th Armored Division, Fort Hood, Texas; Adjutant, 14th Cavalry Regiment, Fulda, Germany; Inspector General, 2nd Army, Fort Meade, Maryland.