There is no question that President Joseph Aoun is attempting to do what no Lebanese president before him has dared to approach so directly: disarm Hezbollah.

His method, which ranges between quiet negotiations, elite consensus, and strategic appointments seems, on the surface, like the only pragmatic path forward. He is trying to avoid collapse. He is trying to avoid war. But he is also repeating the single most damaging mistake in Lebanon’s modern history: conducting national reconciliation through denial, opacity, and exclusion.

The appointment of Hezbollah-aligned former minister Ali Hamieh as presidential advisor for reconstruction may be framed as a gesture of inclusion. In reality, it deepens a dangerous pattern: empowering the perpetrators of dysfunction while sidelining the very public that has paid the price for it economically, socially, and in blood.

If the goal is peace, this strategy will fail. If the goal is justice, it never even tried.

Disarmament Without Justice Is Not Peace

In psychology and in history, we know this much to be true: societies cannot heal from violence without confronting its causes, naming its agents, and building institutions that reflect collective ownership of the future. What President Aoun is offering is a familiar elite bargain; one that prioritizes “stability” over truth, and “coexistence” over responsibility.

But this formula hasn’t saved Lebanon before. It only freezes the conflict while new grievances accumulate. In 1990, the war ended with amnesty but no accountability. In 2005, the Syrian exit came with no national reckoning. And in 2008, after Hezbollah turned its weapons inward, we were told again that stability demanded silence.

Now, even if Hezbollah disarms—which remains far from certain—it will do so on its own terms, preserving its rhetoric, its legitimacy, and its control over entire communities. This isn’t reconciliation. It’s symbolic demilitarization without ideological disarmament. And it will leave behind a fragmented, resentful, and deeply confused society.

The People Are Left Out…Again

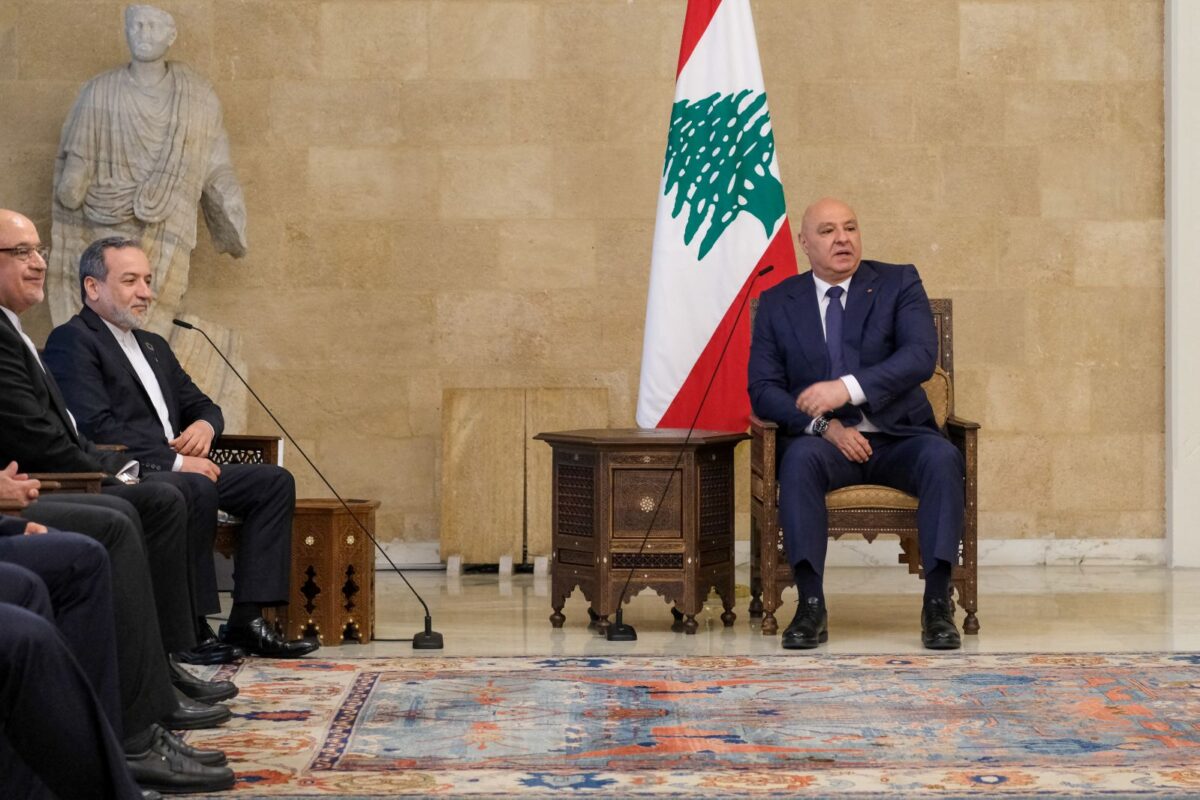

Perhaps the greatest tragedy here is that, once more, the Lebanese people are not invited into the room. Not asked, not informed, not trusted. Disarmament is being negotiated as if it were a technical procedure, not a moral and national turning point. But the cost of this conflict has been borne by everyday Lebanese, not generals, not militia leaders, not presidents. They have lost homes, livelihoods, and futures. They have the right to be part of what comes next.

Instead, they are being handed a familiar bargain: accept a fragile peace brokered behind closed doors, or risk renewed violence. It’s the same logic that every generation of Lebanese leadership has followed. It’s the logic that led us here.

President Aoun May Be the Last to Try, But He’s Still Getting It Wrong

It is not that President Aoun’s intentions are malicious. It’s that they are tragically outdated. He is approaching the Hezbollah dilemma as every Lebanese president since the Civil War has approached national crises: through secrecy, symbolic concessions, and elite pacts. But this is not 1990, and the stakes are not theoretical.

We are not just trying to prevent the next war. We are trying to prevent the disintegration of the very idea of Lebanon.

And while Aoun speaks the language of modernization, AI, reform, and sovereignty, he risks reinforcing the very power dynamics that have made those things impossible. Without a clear, inclusive, and accountable process, any “success” he achieves will be as brittle as the one that followed Taif: a country held together by denial, waiting for the next collapse.

A Final Warning

This is not just about Hezbollah. It’s about the kind of country we want to build and who gets to build it. A Lebanon where armed groups are disarmed but unaccountable, where deals are made but no truths are told, where public trust is treated as expendable, is not a peaceful country. It is a ticking clock.

If we disarm without confronting injustice, without national dialogue, without a collective reckoning we are not moving forward. We are simply postponing the next war, which may be fought over different interests—water, AI, identity—but rooted in the same unresolved wounds.

President Aoun may believe he’s protecting the republic. But in reality, he may be and unintentionally no doubt, ensuring that the next time it breaks, there will be nothing left to salvage.

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a Political Psychologist and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution at the Lebanese American University.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW