TW – this article contains references of child sexual abuse.

Samer Khouzami was shaking.

The dinner guest had left the quieting village house in Kfarhim, Chouf. The sounds of dishes clinking in the kitchen interrupted the silence, his mother was clearing up as she always did after dinner.

“I knew I had to tell someone because I knew that something was wrong,” he remembers.

He walked into the kitchen. Tears filled his eyes as he was gripped with fear and confusion. He crossed the kitchen floor towards the sink and hugged his mother from behind. The tears spilled into hysterics as he tried to find the words that he knew he needed to say, whilst grappling with the fact that his world might have just changed forever.

Her body stiffened with alarm, she responded as any mother would.

“Why are you crying? What happened?”

Khouzami then did what no 14-year-old should have to. He told his mother that the guest that had just left the house, his second cousin and his father’s best friend, had just sexually assaulted him in his bedroom.

The silence of the house swallowed the pain and horror in his voice.

She turned to now face her desperate and tearful son, Khouzami’s mother sadly did what so many have done in this situation.

“She slapped me on the face, and told me to ‘stop being a fem-boy. It’s because of how girly you are, that sometimes it might be misunderstood, it gives the wrong impression,’” he remembers.

“And that was it.”

Reopening a buried wound

Trusting the words of his mother, Khouzami wiped away the tears that stung his reddened cheek and returned to his room. He had ‘learned his lesson’. This was never to be spoken of again.

Like so many victims and survivors of sexual abuse, Khouzami went on with his life. He eventually moved away from the village but took with him the long-term scars of his assault. The fading memory made way for psychological trauma that manifested itself into deep-seated insecurities and low self-esteem, bouts of depression, and crippling mental health battles.

“I had a lot of mental health issues that got me really sick. It took me a while to realize that, what happened that day, was trauma from both the abuser and my mother. And how she reacted, the indirect subconscious-level messages that I got, they shaped my existence,” explains Khouzami.

In May 2021, Khouzami (now 34) met up with an old friend who still lived in the village

They caught up as they always had, his friend bringing him up to date on the gossip from home. However, when she mentioned that a boy from their village had come forward to say they had been sexually abused, his heart dropped.

“It took me back 20 years.”

He pressed his friend to tell him the name of the abuser.

It was the same man; his second cousin, his father’s best friend.

Khouzami says that, once again, he was shaking. He was left with a sense of anger.

“All this time, I believed I was equally guilty of what happened,” Khouzami explained. “It was bullshit – he’s a pedophile, and he’s doing this with everyone, destroying everyone’s lives. No one is doing anything about it.”

“I understood that after 20 years that this was not ok, and I was a victim to this guy, and I had to be silent for 20 years, but not anymore.”

Khouzami then took to social media to share his story.

View this post on Instagram

Encouraging others to speak up

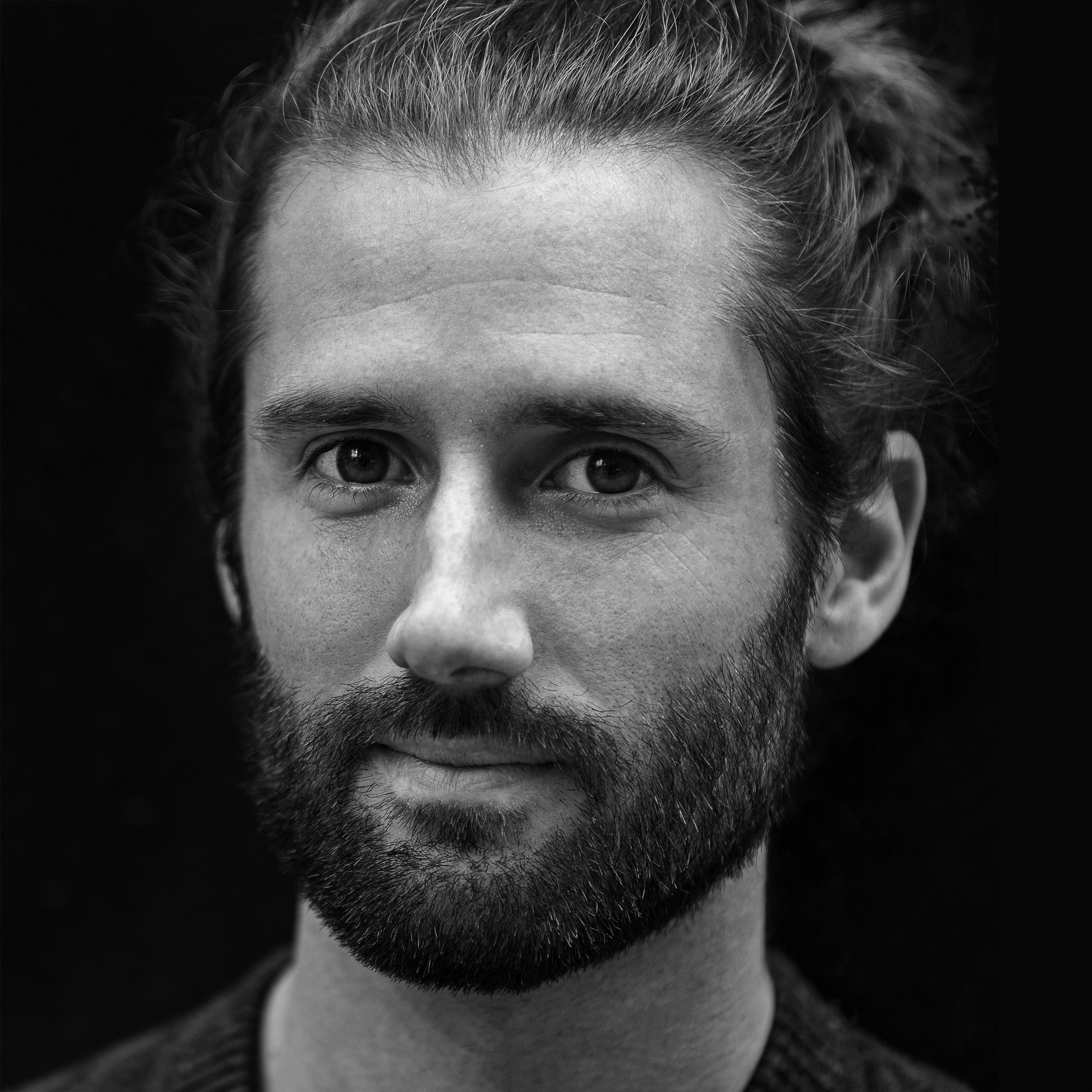

In the time since leaving Kfarhim, Samer Khouzami has built a hugely successful career as a world-renowned make-up artist, eventually owning his own brand of cosmetics. He has a studio in his name in Ein El Tineh, Beirut.

To compete on the international market, Samer has fostered a considerable profile online, producing hundreds of instructional videos of make-up transformations featuring his products and techniques. ‘Samer Khouzami’ has become a house-hold name. He has built and nurtured a digital following, including an audience of 2.2 million followers on Instagram.

Within hours, the video detailing his harrowing story had been shared across the web, appearing on devices and screens across Lebanon, the Middle East and beyond. In the eight-minute clip, Khouzami struggled to hold back the tears as he recounted the traumatic moments which changed his life, the moments he says his childhood was taken from him.

The response was overwhelming.

“We knew there was going to be something strong, especially from my audience to hear it from me. But we didn’t expect this amount of reaction,” Khouzami told NOW.

In the weeks since Samer’s video was posted online, he has received dozens of messages from people who have experienced similar trauma.

“There are people who are in their 50s and 60s who shared a story that happened to them when they were teenagers or even younger. They said they never even spoke about it until that video, it was the first time they felt they had the courage to share.”

“It’s really heartbreaking to see that so many people lived with trauma for 20 years or 30 years, believing it was their fault, that they had something to do with it,” says Khouzami.

A widespread problem

In posting the video and sharing his story, Khouzami uncovered just some of the stories behind one of Lebanon’s most unpunished types of crimes.

According to a study released in 2008 by Save the Children, NGO Kafa and the Ministry of Social Affairs, it is estimated that as many as one in six children in Lebanon is subjected to a form of sexual abuse. The survey showed that most incidents, 55 percent, happen at home, repeatedly, by a known male perpetrator. Another 6 percent happen at school, 5.5 percent in a neighbor’s house and 5.1 percent in a relative’s home.

“We were born in a society wherein some contexts disclosure isn’t encouraged, and the blame is put on the [abused] child. This is why we see people disclosing incidents that happened to them years ago,” says Farah Salhab, Gender and Disability Inclusion Specialist at Save the Children, Lebanon.

“Child abuse and exploitation is prevalent, and usually it is underreported,” says Salhab.

Another comprehensive study in 2015 by the Ministry of Social Affairs, found that out of the over 2000 people interviewed, 53.9 percent of the girls were exposed to sexual abuse, while the percentage is just slightly lower for boys – 46.1 percent. Most boys and girls experience the first incident when they reach the age of 14, but some also reported sexual abuse at younger ages, even 10 years old.

The study also stressed a strikingly low level of awareness among parents, manifested in their blind trust of their surrounding neighbors, friends, relatives and acquaintances, and the transfer of this excessive confidence to their children by allowing them to always or sometimes, sleep with those persons alone (50.6 percent) or to go out with them (61.8 percent) or visit them alone (67.4 percent).

The study also revealed that a high percentage of children who have been victims of sexual abuse remain silent – 49.4 percent. The authors of the study stress on the lack of awareness and education on what has actually happened, but experts say there is more to it than “not knowing”.

“The classic scenario is that sometimes the victims are threatened by the perpetrator. Children would not disclose because they are afraid the perpetrator would harm them or their parents. Sometimes, depending on the age and stage of development, they worry that if they disclose their parents will get mad at them or feel sad,” explains Salhab.

Salhab says that increased awareness-raising, like Khouzami’s video and work done by NGOs, means that people are able to reflect on their own experiences and feel more compelled to open up.

“We are now seeing people disclose more than ever,” she says.

A toxic backlash

As well as the messages of support, Khouzami is also on the receiving end of a toxic backlash.

“People started to relate the way I am revealing myself with what happened to me. I saw comments saying, ‘Oh he is this way, because this is what happened to him.”” says Samer.

Khouzami has never publicly discussed his sexuality or gender identity, yet some of the responses he has received reveal common and deeply ingrained homophobic beliefs, implying that his sexuality is explained by the sexual abuse he experienced as a child.

These ideas are typical when discussing sexual assault of minors, reflecting common misconceptions that are as delusional as they are dangerous.

“While there is a readiness to subscribe to the mythology that homosexuality is caused by the sexual assault of minors, particularly when it is against young boys,” explains Tarek Zeidan, Executive Director of Helem, an LGBT rights NGO in Lebanon.

“There is little to no discussion on the actual prevalence of sexual assault against minors where the overwhelming majority is from cis-hetero men towards girls and younger women.”

Zeidan says that this typical response is meant to concentrate on sexual molestation of minors of the same sex or gender identity in an effort to “condemn homosexuality and not to talk about all of sexual assault and harassment and molestation for minors in general.”

“When you actually confront the shocking prevalence of this in our society, we need to ask ourselves, ‘Why isn’t it being discussed? What are the reasons for that? What are people trying to protect? What are people trying to justify?’”

The legal system exposes the victim

Certain societal attitudes have seemingly contributed towards creating a culture that stifles and silences victims of abuse, preventing more children from coming forward.

Those few that make the choice to disclose their experiences and seek legal action face navigating a system that too often works to protect the perpetrator at the expense of the survivor.

“The primary obstacle in adjudicating cases of sexual violence against minors is the question of evidence and proof. By nature, these crimes occur in the private setting, and are difficult to prove with conclusive evidence,” explains Lama Karame, a lawyer at Legal Agenda, nonprofit research and advocacy organization.

Laws that have been passed to protect victims of sexual abuse and harassment often lack any meaningful punishment. According to a study on judicial decisions conducted by Legal Agenda, the average penalty of sexual violence crimes committed against minors, when there is a conviction, is three years and ten months of imprisonment.

The laws also often fail to protect the privacy of the victims, meaning that those who do not wish to go public might be deterred from filing a complaint.

“The main thing to acknowledge is we don’t have a penal policy or general criminal policy in Lebanon, like elsewhere meaning that punishments may vary considerably from court to court,” Karame says.

Khouzami, who is possibly among the first high-profile victims of child sexual abuse going public in Lebanon, is determined to use his power and influence to take on his abuser in what has the potential to be a landmark case.

“I’m not going to stay silent. I am going to do everything in my hands to make this guy pay,” he said in his video.

Discussions with his legal team are ongoing, he explains.

In doing so, he hopes to keep the conversation going around protecting children from sexual abuse, raising awareness as the first step to bring about cultural, societal, and maybe even legal change in Lebanon.

For the kind of change that is needed to protect children in Lebanon, Zeidan believes that getting behind survivors is the key.

“What would be amazing, is if more and more people are encouraged to talk about their experiences, so it becomes something that we all discuss, and not just in isolated incidents.”

However, the onus does not solely lay on the survivors and victims of sexual abuse.

“We should be ready to support and stand behind and believe every single one of these people coming forward. We need to automatically give these people the support they need, create spaces in which they feel safe, heard, understood, appreciated and believed.”

Khouzami agrees.

“We need to talk about it more. And I am not going to stop.”

Matt Kynaston is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. He tweets @MattKynaston.