Friday’s cabinet session was meant to be a turning point. The Lebanese Army’s plan to restore the state’s monopoly on arms is finally on the table. But before ministers even sit down, the political chessboard is already shifting.

Berri’s Reframing: All of Taif

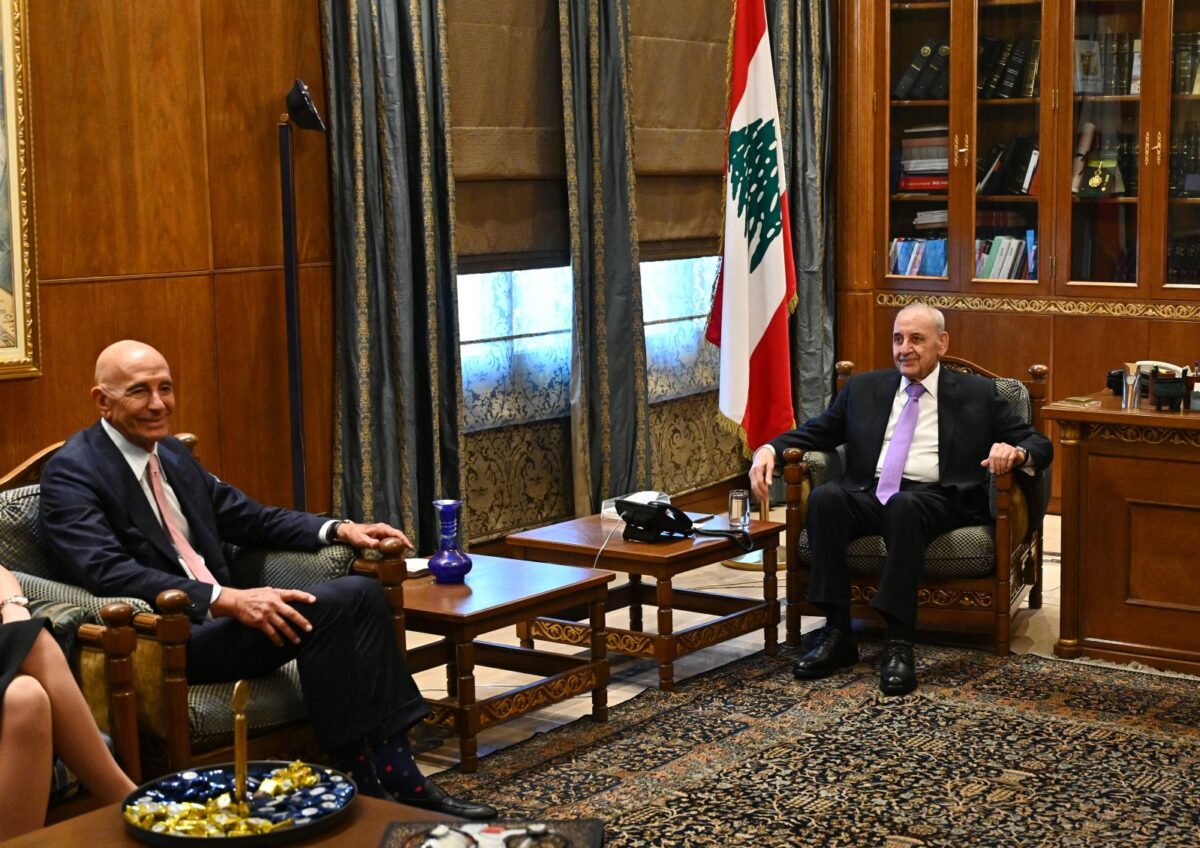

Speaker Nabih Berri isn’t rejecting the debate on militias’ weapons. He is reframing it. His message apparently seems to be: Yes, we can talk about arms but only if we implement the entire Taif Agreement. That means abolishing sectarian quotas in parliament, electing MPs on a non-sectarian basis, and creating a sectarian Senate to safeguard communal rights.

It is a clever move. On paper, it is faithful to Taif. In practice, it tilts the system toward Shia demographic weight, far greater than the fixed quota of 27 MPs they hold today. Other sects see this as demographic domination disguised as reform. Which is why the Cabinet is unlikely to bite.

Why the Cabinet Won’t Follow

Most ministers want the arms question settled first, then constitutional reform later, perhaps even beyond Taif. They will resist tying disarmament to systemic change that advantages one group. That refusal, however, will once again allow the Shia leadership to frame the process as targeting and exclusion.

The Shia Leadership’s Bind

Here lies the bind: the Shia electorate has paid a heavy price in blood and destruction. Every family has martyrs; entire markets and villages have been lost. To give up weapons with nothing to show in return would look like betrayal.

Berri understands this. His maneuver offers Shia leaders a political commodity to sell back to their base: not just disarmament, but a new system where their community is central.

Hezbollah’s Outsourcing to Tehran

But Hezbollah’s calculation goes further. For them, the real bargain is not in Beirut but in Tehran and Washington. They are betting that weapons can be traded in regional negotiations; sanctions relief or geopolitical recognition in exchange for gradual disarmament. This is the true outsourcing of Lebanon’s sovereignty: reducing national security to a chip in U.S.–Iran talks.

The Cost of Paralysis

This is why disarmament will not happen on Lebanese terms. Berri maneuvers domestically, Hezbollah waits for regional dividends, and the Cabinet stalls. The session risks becoming theater while the real deal is written abroad.

And yet, the irony is clear: Lebanon’s people — Shia, Sunni, Christian, Druze, and all the other minorities — are not asking for foreign bargains. They are asking for a state that protects them equally. Until arms are reclaimed as a national issue, not an Iranian one, disarmament will remain perpetually deferred, and sovereignty perpetually out of reach.

Ramzi Abou Ismail is a Political Psychologist and Senior Research Fellow at the Institute for Social Justice and Conflict Resolution at the Lebanese American University.

The views in this story reflect those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect the beliefs of NOW