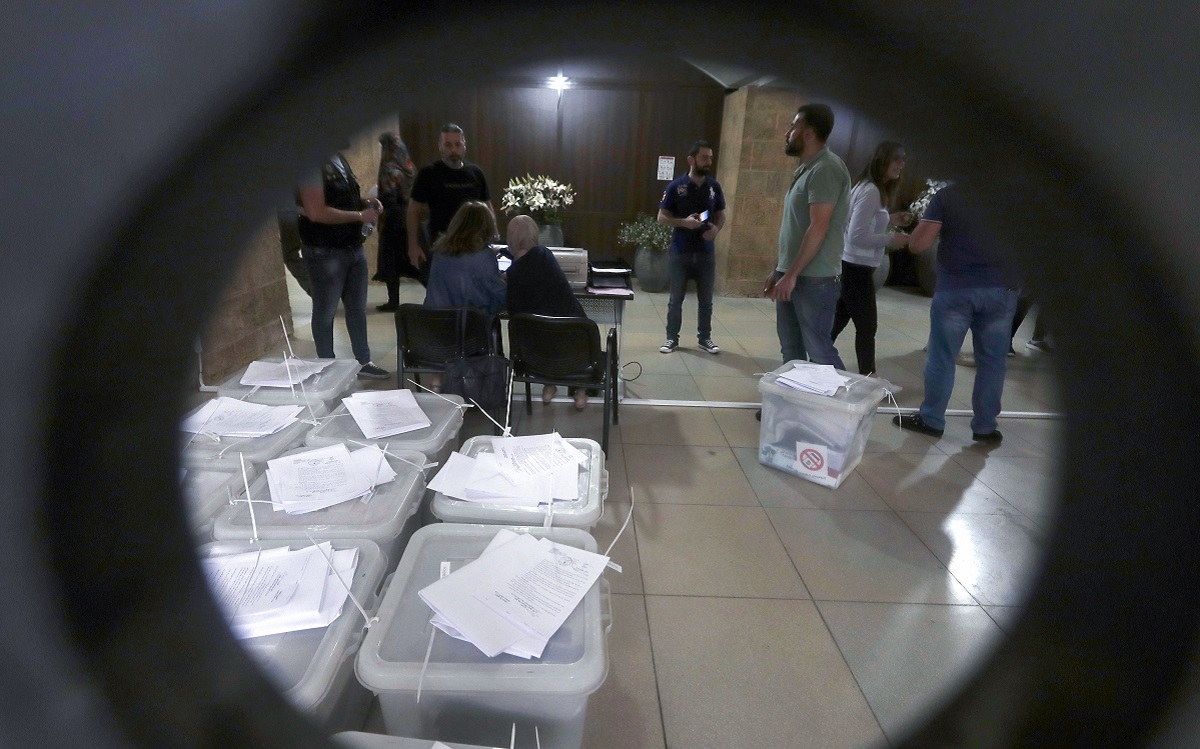

As Lebanon heads to the polls this Sunday, only a handful of chronic optimists believe that the final outcome will significantly alter the country’s decrepit political landscape. Yet, contrary to this bleak outlook, elections remain instrumental for a country fighting for its survival.

Many factors preclude real change from transpiring. The current electoral system that will regulate the upcoming elections is a bastardized version of the proportional representation model. It is tailored to secure the re-election of the ruling elite which has used corruption and Hezbollah’s weapons to obstruct the October 17 revolution from carrying out its plans for transitional reform.

Be that as it may, the Lebanese at large – some of whom are beyond convinced of the futility of voting or those who will vote – need to remember a few essential facts when they stand in front of the ballot box.

Lebanon’s recovery hinges on their realization that their country is no longer unique nor will its salvation come through a Taif-like agreement that would see the Arab Gulf refloat Lebanon’s sinking economy.

Those who will vote Sunday need not forget that voting for change does not only mean voting out the corrupt politicians, but rather an open confrontation with those who protect them. Over the last few years, the Lebanese have identified the Militia (Hezbollah) and the Mafia (the corrupt political elite) as forging an unholy alliance through which they control Lebanon.

Lebanon’s recovery hinges on their realization that their country is no longer unique nor will its salvation come through a Taif-like agreement that would see the Arab Gulf refloat Lebanon’s sinking economy.

In essence, such an analogy is flawed as this dichotomy assumes that Hezbollah is merely protecting these corrupt individuals and is not really accountable nor participating in swindling the resources of the Lebanese state and its people, who saw their lifesaving usurped by a banking system complicit with the corrupt ruling establishment.

Hezbollah might have started off in 1982 as an ostracized Iranian satellite. However, after 2005 and the assassination of late Prime Minister Rafik al-Hariri, Hezbollah became the trust fund manager for a corrupt clientelist system, which under its watchful eyes became one of its major sources of funding for its expansionist project on behalf of Iran. Thus, contrary to what it claims, Hezbollah is not merely the enforcer to this corrupt political system, but, in fact, it sits on the board, as well as chairs it as needed.

In simple terms, Hezbollah is not merely the guardian of the temple of corruption but the temple itself. While it hides its corruption well, it is living off the misery of the Lebanese people and, more specifically, the Lebanese Shiite community it claims to protect.

Consequently, Hezbollah presides over an assortment of cartels, ranging from private generators, waste disposal schemes, smuggling and tax evasion, narcotics and other black-market entrepreneurial endeavors.

Indeed, the aforementioned facts should be the voters’ measuring stick through which they gauge those for whom they wish to vote. Many of the factions who peddle a pro-sovereign rhetoric have no problem with sharing the spoils of the state with Hezbollah. Such dealers should be called out by those who believe in real change.

While the Lebanese system did foster the seeds of its own destruction, the reason for the current crisis is not merely corruption, but the fact that Hezbollah and the entire political establishment have put corruption on hyperdrive. Yet the perpetual perfect storm that the Lebanese are experiencing won’t simply go away after the election.

Hezbollah presides over an assortment of cartels, ranging from private generators, waste disposal schemes, smuggling and tax evasion, narcotics and other black-market entrepreneurial endeavors.

By casting a vote against this symbiotic relationship between Iran and their access to corruption, the Lebanese would take one step in the right direction of a long and arduous quest to reclaim their country.

The elections on Sunday transcend just picking the 128 so-called lawmakers, as it will set the stage for a much bigger confrontation on October 31, when the term of President Michel Aoun expires. As projected, Aoun will refuse to vacate the position or perhaps, using Hezbollah arms, will ensure the office will remain vacant until circumstances allow for the election of his son-in-law and political heir Gebran Bassil.

Coincidently, to avoid such a nightmare from becoming reality, the Lebanese, especially those who think boycotting the elections is a wise decision, have to remember that Hezbollah and the ruling establishment are nourished by the frustration and desperation of those who choose to normalize and cohabitate with this regime of serial killers. Hezbollah and the other classical parties appeal to their voters’ primordial sectarian instincts portraying the vote as an existential choice, linking the fate of their supporters to theirs.

In reality, the existence of Lebanon and its people hinge on voting such a flawed logic out.

This election will not change much, but at least it will remind the Lebanese that the only way for them to live in peace and enjoy modern-day amenities from water, electricity, medicine, and the internet is to demand and fight for a modern state, where criminals cannot run for office.

Makram Rabah is the managing editor of NOW and a lecturer at the American University of Beirut, Department of History. His book Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (Edinburgh University Press) cover collective identities and the Lebanese Civil War. He is on Twitter and on Instagram.