In a new series of events, AUB is uncovering Lebanon's hidden history, bringing to light forgotten stories of the civil war through public history and academic exploration

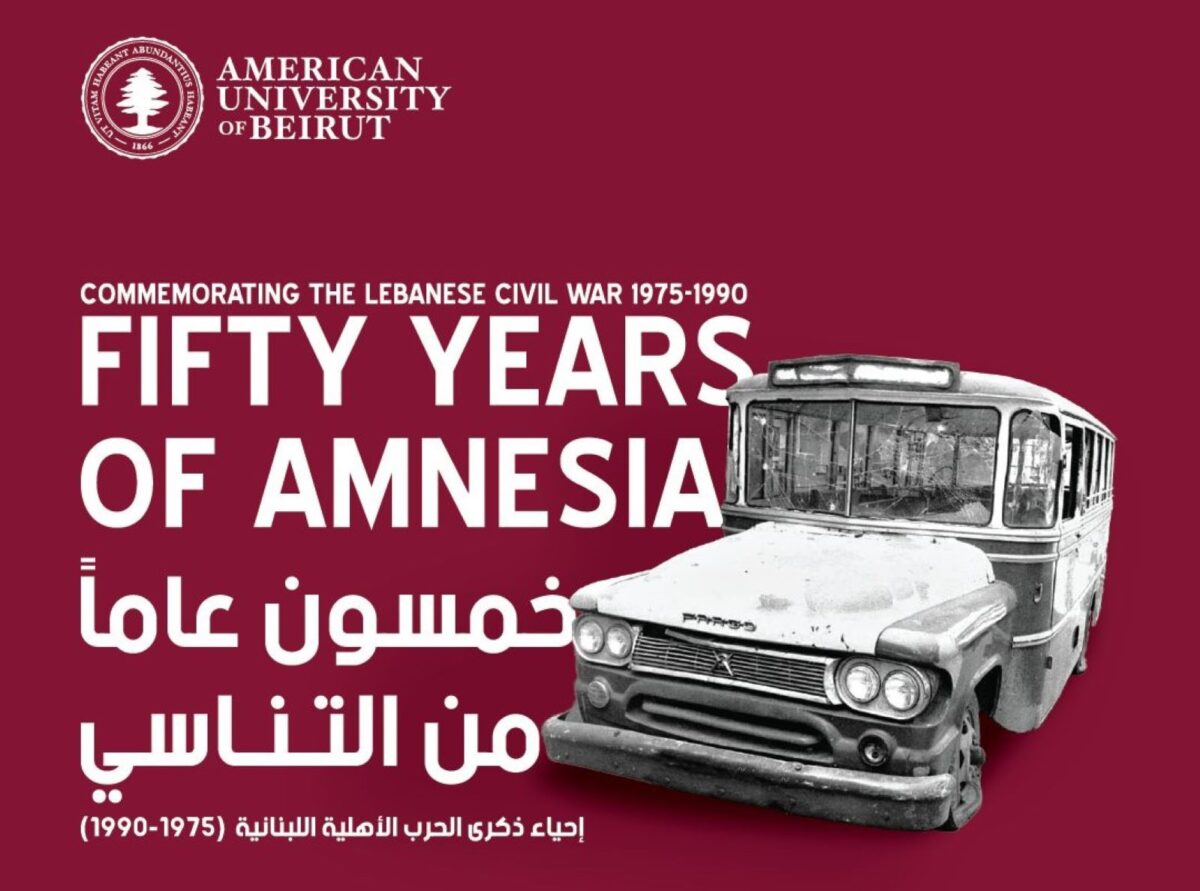

Every April, the anniversary of Lebanon’s civil war passes quietly—no sirens, no public ceremonies, no national day of mourning. Despite a war that reshaped the country, left over 150,000 dead, and permanently altered its political and social landscape, it remains largely unspoken. But memories have a way of resurfacing, even when deliberately buried. This year, a series of events at the American University of Beirut under the title “50 years of Amnesia” attempts to break that silence by asking: What do we remember? Who tells the story? And what happens when a nation chooses to forget?

The series of events marks 50 years since the outbreak of Lebanon’s civil war. This archival project reconstructs how the war seeped into everyday life and collective memory. Through curated photos, family archives, and press clippings, it goes beyond the battlefronts to show the personal side of the war—breadlines, bomb shelters, lost neighborhoods, and fractured identities. Complemented by film screenings, talks, and panels with historians, artists, and survivors, the exhibition invites a reckoning with Lebanon’s still-festering wounds.

The war, which spanned from 1975 to 1990, was not just a conflict of arms, but a violent eruption of political, religious, and social tensions—tensions exacerbated by regional powers like Israel and Syria. It displaced hundreds of thousands, disrupted daily life, and left deep scars on Lebanon’s collective psyche. Yet, despite its monumental impact, the war remains downplayed in public discourse. The absence of a national reckoning has left unresolved tensions at the heart of Lebanon’s fractured political and social landscape.

Lebanon still carries the weight of its unresolved past, especially as tensions with Israel continue to escalate. The country seems stuck in an endless cycle of crises, with its people repeatedly facing new waves of violence. Despite the lasting impact of each conflict, politicians avoid confronting the underlying issues, leaving the wounds unhealed. As the cycle continues, Lebanon struggles to move forward, caught between its history and an uncertain future.

A History of Amnesia

Historian Charles Hayek believes that Lebanon has been trapped in a cycle of imposed historical forgetting since the end of its 15-year civil war. “In 1991, the Lebanese Parliament voted a general amnesty law,” he explained. “It was terrible. It exempted the majority of the warlords from their wartime crimes and transformed them into politicians.” According to Hayek, this law not only protected perpetrators but also fostered an official amnesia surrounding the war, hindering any real process of national reckoning.

Hayek described AUB’s project as “truthful to AUB’s mission to educate,” adding that the role of the department is to “examine, question, and critically analyze historical events.”

For Hayek, the value of this initiative lies in its ability to challenge emotional and polarized narratives that have dominated public memory. “One of the reasons why we have a problem dealing with the war is that we don’t have a critical analysis approach. We have a very emotional approach,” he said. Many young people, he noted, inherit unexamined narratives from their families. “Students in their twenties think like their parents who took part in the war. Minds that did not change. And this is dangerous—it normalizes violence.”

He emphasized that the civil war’s dominant narratives have focused on heroism and political justification, leaving out the everyday experiences of civilians. What’s missing from the overall picture, is the daily life of civilians.

“They don’t tell you how people lived in shelters, without access to education, food, or medication—under daily threats of death from snipers and shelling,” Hayek said.

The initiative, titled 50 Years of Amnesia, aims to fill that gap by using public history as a tool to democratize access to academic knowledge. Hayek said that public history can serve as a “shortcut to history,” making it more accessible and helping young people engage critically with the past. “This is the first time on a large scale that public history is used to challenge dominant narratives and provide fresh, academic, solid interpretations of the war.”

In post-conflict societies, he explained, there are often two approaches to dealing with painful pasts: creating fictional narratives or forgetting entirely. Lebanon, he argued, chose both. “We say this is the war of others on our land. That’s a fictional history—it disregards local responsibility,” he said. And with the General Amnesty Law, he added, forgetfulness was codified into law.

“To remember, I need justice,” Hayek asserted. “I need the ex-warlords to be taken to court. Instead, we imposed amnesia. We don’t talk about the war. We talk about something very folkloric, very kitsch.”

Events of Multiple Mediums

For Varak Ketsamanian, assistant professor of history at AUB, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Lebanese Civil War is less about revisiting the past than it is about shaping the future. “History doesn’t teach us anything but it actually shows us what is or may be possible,” he told NOW, pushing back against passive views of historical learning. The department’s goal, he explained, is to challenge the collective amnesia that followed the war and create a space for critical reflection.

The initiative blends academic panels with artistic expressions—music, installations, and performances—to accommodate diverse ways of processing trauma. “Artistic expressions may help create a broader and a more inclusive space for myriad interpretations,” he said, especially for those who struggle to articulate their experiences in formal language.

Rather than focusing solely on those who lived through the war, the department placed younger students at the center of the commemoration. “We made sure young students are also actively involved in the organization, coordination, and realization of these events,” he said, adding that student engagement is part of a broader pedagogical model that connects history to lived urban and social realities.

To avoid a single dominant narrative, the planning process welcomed input from a wide range of participants—including scholars, journalists, actors, and administrators—ensuring what he called an “open-ended” approach. Events will extend through April 2026 to allow more voices to shape the remembrance.

Among the voices that are rarely heard on the topic of the civil war are that of women. Lina Abou Habib, director of the Asfari Institute at the American University of Beirut, told NOW that any serious attempt to reckon with Lebanon’s civil war must confront the gendered violence it produced—and the silence that has followed. “Those who have made people disappear, those who have raped women, they are still in power,” she said. “So it’s all the more convenient to forget… to literally get away with murder—literally and figuratively.”

Abou Habib emphasized that discussions about the war have largely erased women’s experiences, despite a vast body of global literature showing how conflict impacts women and girls in multifaceted ways. “War, especially one that lasted over 15 years, preys on the invisibility and vulnerability of women,” she explained, citing lawlessness and toxic masculinities as enabling factors. In contrast to international efforts like the war crimes tribunals for Rwanda and Yugoslavia, Lebanon has never formally examined wartime sexual violence.

She called for moving beyond characterizing women solely as victims. “There is a diversity of roles and impact,” she said. “I want us to move away from best characterizing women and girls as passive victims, because this is not the reality.” Still, she pointed to the silence surrounding sexual crimes, with only a handful of women coming forward—often decades later. “Trauma is generational,” she added. “What is happening to the generation of women and girls carrying this trauma?”

Risk of Repeating the Past

Memory is not only personal but also political. Owning up to Lebanon’s history could be a first step toward justice. “People carried arms and killed each other, and kidnapped each other, and raped each other,” Abou Habib said. “We have to understand the war, revisit it, and be reflexive about our own role in shaping this narrative.”

The cost of erasure, she warned, is repetition. “The first result of moving on is actually repeating the violence,” she said, pointing to how postwar Lebanon became a militarized society—one that remains unsafe for women and marginalized communities.

The project at AUB is set to uncover stories long buried—either deliberately forgotten or simply waiting for the right moment to resurface. And that moment, it seems, has finally come. Many in the younger generation remains unaware of the full scope of Lebanon’s civil war, and will likely be met with shock as new layers of history come to light. Much of this is due to limited access to records and an educational system that has largely erased the war from its curriculum.

“You can’t imagine asking a student what the Taif Agreement is, and they don’t know,” said Abou Habib, recalling moments in her classroom when students stared blankly in response to questions about the agreement that ended the war. “The overwhelming majority doesn’t know,” she said. “And their parents refused to answer.”

In a country where silence has too often replaced reflection, this project may offer a vital first step toward collective healing. By breaking generational silences and reintroducing forgotten histories into public discourse, it pushes back against the erasure that has long dominated Lebanon’s postwar reality—and invites a new generation to confront the past with clear eyes and critical minds, in hopes that a new future will unfold.