Layla Kanso, 65, lives alone in her apartment in Haret Hreik, Beirut. She has no source of income besides what her three brothers are able to spare for her.

For months, since the economic crisis worsened as the state ran out of money for subsidies on fuel and basic needs, including food, her expenses dwindled to just food and medicine.

Health minister Firas Abiad announced earlier this month the partial lifting of subsidies on medicine, including on some drugs for chronic illnesses. This resulted in a price hike on most medicines.

According to Abiad, the Lebanese state now spends $35 million on medical subsidies each month, down from $130 million prior to subsidy cuts. But that means that most Lebanese, like Kanso, have to spend much more on medicine, and many have to simply give up treatment.

“I suffer from high blood pressure and I’m currently on my last box of medication. But if I can’t afford it then I’m going to stop it,” Kanso told NOW.

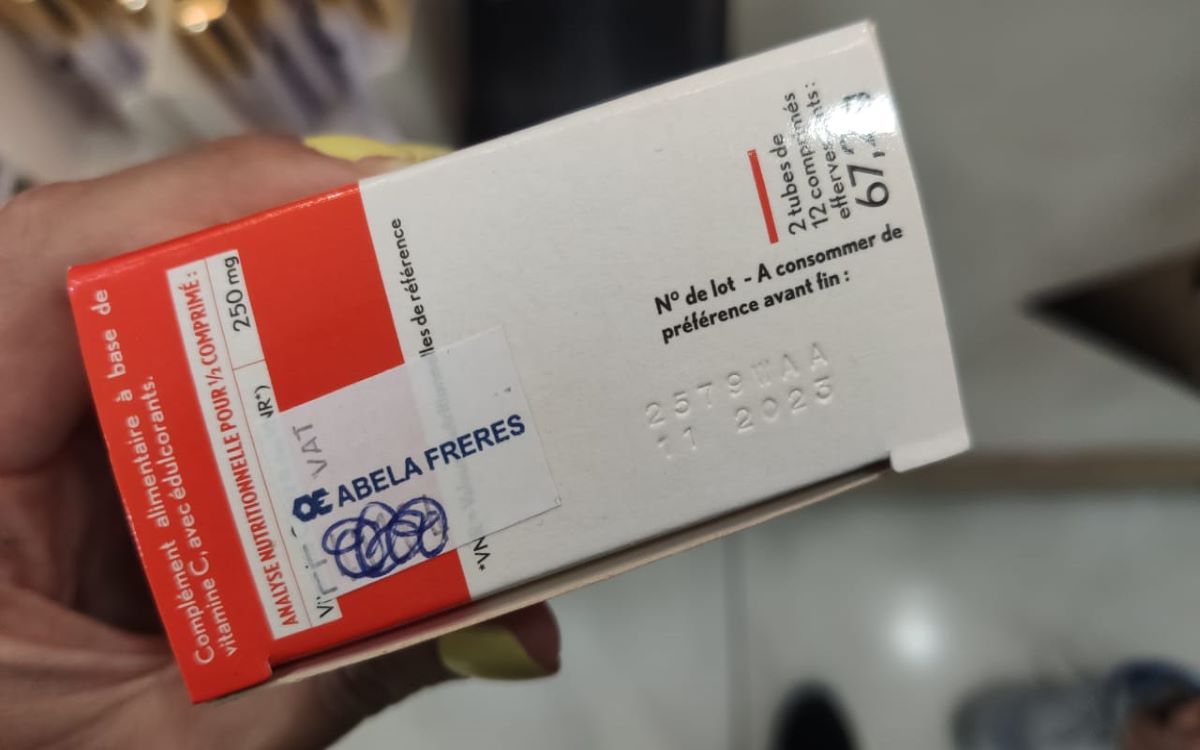

Kanso has already stopped treating her stomach ulcers and degenerating eyesight because of the increasing prices. One box of vitamins prescribed to improve her eyesight now costs 80 percent of the minimum wage in Lebanon.

“I used to take specific vitamins for my eyes that are now worth 400,000 LBP, compared to their previous price of 30,000 LBP,” she said.

And that isn’t the only sacrifice she’s made.

“I no longer buy meat or chicken and rarely buy cheese. I eat very basic food made up of rice, lentils, and eggs. I save up the money to be able to afford medicine,” she stated.

Proper healthcare and medication have become luxuries for most Lebanese, as treating a chronic illness now costs most of an average income. This is assuming the medicine is available in the first place.

At the top of a new priority list

Lebanon experienced a medicine shortage in the summer, with pharmacies closing their doors as importing companies stacked up vital subsidized medicine and waited for subsidies to be lifted and prices to increase. The state was running out of resources, payments were late, and businesses, including medicine importers, did not trust that the government would pay in time.

Former interim Health minister Hamad Hassan raided numerous medicine storage facilities in search of violations. Meanwhile, as NOW reported during the shortage, diaspora initiatives helped provide lifesaving medicine, delivered by expats in suitcases.

But while most medications are now once again available in pharmacies, albeit at much higher prices, various inequalities have become much more pronounced, pharmacists say.

“It’s not only about the price of the medication, it’s also about the availability. Not all pharmacies carry all medicines so people have to look everywhere,” Tareq, a pharmacist in Beirut, told NOW. For example, medicine that treats diabetes is scarce at the moment, he said.

Two women entered the pharmacy. The first one held a prescription in hand and said she was shocked to find the medicine she asked for.

“I’ve been looking all over for this blood pressure medicine for my mom, I can’t believe I finally found it. I don’t care about the price, I just need it,” she told NOW. She then rushed to get the money from her car.

The second woman then entered with another prescription in hand for a strong pain killer to soothe a toothache. When she heard the price she then asked for an ice cube.

“I see these people all the time. She knew she couldn’t afford the medicine, she was just using it as an excuse to get free ice. Some people can’t even afford that,” the pharmacist said.

Tareq also explained that, while inequalities have become more apparent, the number of people coming to his pharmacy did not drop. The reason, he says, is that most people save money by skimping on food and other goods to be able to afford the necessary medication.

“Some people used to prioritize outings, certain food, and some even luxurious products. Now they can only afford the bare necessities. So people’s priorities changed, now medicine is no longer taken for granted on the monthly budget list, it’s the top priority.”

Annoir Shayya, 31, a doctor of Hematology and Oncology at LAU Medical Center, explained that buying medicine is already, for most Lebanese, a matter of sacrifice. Many use the last of their life savings to buy needed medications, while some parents must choose to feed their children, rather than afford medication for their own illnesses.

Staying afloat

Shayya, 31, says he just started out his career, just seven months ago.

“You start wondering why you even studied medicine, you can’t help people nor can you do your job well,” the doctor told NOW.

“With cancer treatments, there are also other medications used to treat side effects such as intestinal problems and nausea. Leukemia, for example, renders the person’s immune system weak and makes them more susceptible to infections,” the doctor explained.

In order to procure these medicines for patients in need, Shayya says he had to develop a new skill: navigating his social network to find ad-hoc solutions through friends, other patients and charities.

His latest attempt was at procuring Venetoclax, a drug used to treat leukemia, through another patient that had kept it hidden. He also relied on NGOs such as Barbara Nassar Association for Cancer Patient Support to help with the sourcing process.

Shayya described a growing disparity amongst the Lebanese classes where the dollar-earning citizens and residents are unfazed by a 10 million LBP (the high end of the current average salary in Lebanon) deposit for hospital admission, while others are unable to afford 400,000 LBP for a test.

Locally manufactured medicines have been around for years, and are more affordable than imported medicines. Pharmacists and patients alike, however, have only recently turned to the local producers, and remain wary over the unregulated industry and lack of supervision that has allowed fake painkillers and placebos to be sold on the market.

“We have really good medicines that we should invest in, instead of putting our money on imported ones. But we have a culture that fears everything Lebanese made. We probably blame it on the lack of supervision on a lot of things,” Shayya stated.

Tareq also explained that his pharmacy always carried local alternatives but that not everyone was interested in them, due to doubts over quality.

Shayya considers the personal efforts made by the Lebanese abroad, NGOs and healthcare centers that offered cheap consultations the only things that have kept the healthcare system afloat.

“The number of patients isn’t going down, because we have fewer doctors now so we have more workload. There are ways to get a good consultation for little to no money but treatment through the right medicine is still questionable,” the doctor explained.

Relying on charity

Kanso, who faces the impossibility of treating her blood pressure, heard that there were some health centers that offered free consultations and medication, but she says she doesn’t know where to find them.

The ministry of health has 248 centers spread out all over the country that provide primary health care services that the ministry detailed as such; mother and child health, nutrition, environmental health, communicable and non-communicable diseases, immunization, mental health, awareness campaigns, and dental health.

The Order of Malta in Lebanon has nine Community Health Centers that follow the Primary Healthcare Program set by the Ministry of Public Health in Kobayat, Khaldieh, Barqa, Zouk Mikael, Kefraya, Roum, Siddikine, Yaroun and Ain El Remmaneh, and two in collaboration with the Lebanese Army in Rmeich and Raas Baalbek, as well as seven mobile medical outreach operations in Kefraya, Ras Baalbek, Akkar, Siddikine, Yaroun and Zgharta and Roum.

“Following a vulnerability assessment, the patient’s participation of his fees vary between 18. 000 LBP, 3.000 LBP or completely for free ” Oumayma Farah, head of communication at the Order of Malta Lebanon told NOW.

So far, the centers have been able to navigate through medicines provided by the ministry – mainly the ones provided for chronic illnesses- as well as alternatives they receive using their channels of donations. They also maintained their minimum consultation symbolic participation fee of 3,000 LBP whenever applied according to the vulnerability assessment so that “the patients don’t feel like they’re begging for their health basic rights ” Farah explained.

The organization has to rely on donations to be able to cover the patients’ fees. The process begins with a checkup with the family doctor that then refers the patient to the required specialist or medical exams if needed, and prescribes medication, to be taken from the center’s pharmacy.

Farah described a spike in the number of medical acts performed in the centers rising from 200,000 in 2019 to 450,000 in 2021.

She also said that because of the rising needs, the charity is going beyond primary healthcare and is launching on December 1st a specialized clinic for neurodegenerative diseases, mental health and oncology consultations and exams, in Achrafieh (facing Hôtel-Dieu de France). The plan is to later relocate it to a revamped center in Ain el Remmaneh in the first quarter of 2022.

Another issue such health centers face is the hesitancy of many patients. The reasons, Farah explains, vary from feeling undignified due to the shock of suddenly finding themselves in need of asking help from a charity, to dreading the tiresome process of having to wait in line for hours before receiving consultation due to the high volume of patients.

“Many people used to have insurance and didn’t need anyone to help them with their medical coverage and now it feels weird for them to start asking for help [from a charity]. Our message to these people is your health is your priority, we stand by your side, just show up and we’ll take care of you in the best possible way,” Farah said

Dana Hourany is a multimedia journalist with @NOW_leb. She is on Instagram @danahourany and twitter @danahourany