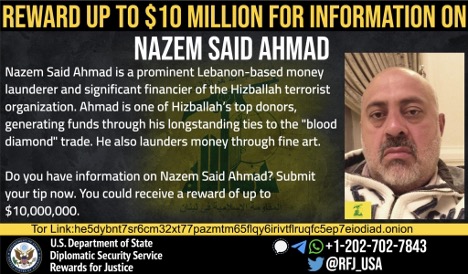

Last April, art and diamond dealer Nazem Ahmad was sanctioned by the United States Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) – along with more than 50 individuals and organizations – as part of a systematic campaign against a vast international money laundering and tax evasion network used to launder money and provide funding for Hezbollah.

For years, Ahmad skirted international regulations and safeguards by using business associates, front companies and family members in a complex ‘layering’ scheme of cash transfers, bypassing cash reserve restrictions to avoid investigation by financial authorities.

Through operations, both legal and illegal, across Lebanon, Dubai, the UAE, South Africa and Hong Kong, Ahmad took advantage of the often opaque and inscrutable nature of the global luxury commodities market, focusing primarily on diamonds and art. Ahmad also possesses a vast personal collection of artworks including pieces by world-famous artists Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol and Antony Gormley.

While his international assets have now been frozen, no action has been taken against Ahmad in Lebanon and he remains at large, despite having evaded countless taxes and depriving the Lebanese treasury of much-needed tax revenues during a time of crippling national crisis.

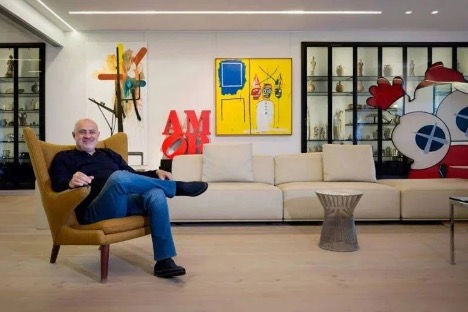

While Ahmad has been placed on the sanctions list, his flamboyant lifestyle has yet to suffer as he continues to buy and sell art, scattering them across the lobby of his lavish building in downtown Beirut – an area known for its high-end restaurants and cafes.

Ahmad reportedly hangs one of the works of the renowned neo-expressionist American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat in the lobby of his building worth millions.

This picture released by OFAC shows Ahmad in his penthouse surrounded by priceless works of art, items that he acquired from auction houses and art dealers. The artwork entitled The Three Pontificators by Jean-Michel Basquiat (center) was purchased by Hezbollah’s diamond dealer for a whooping £2,210,500 (over $2.8 million), while the AMOR statue as well as the Untitled (Baum 54) by Albert Oehlento its left can both fetch a million dollars.

Ahmad nonchalantly parades his wealth in and around Beirut lavish restaurants and hotels, while the Lebanese authorities have yet to question him about the source of his wealth. In the past Ahmad is said to have gifted Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Hezbollah a large diamond to show support to the “Resistance”, diamonds he allegedly acquired from his trade in blood or conflict diamonds.

Blood Diamonds meets Blood Art

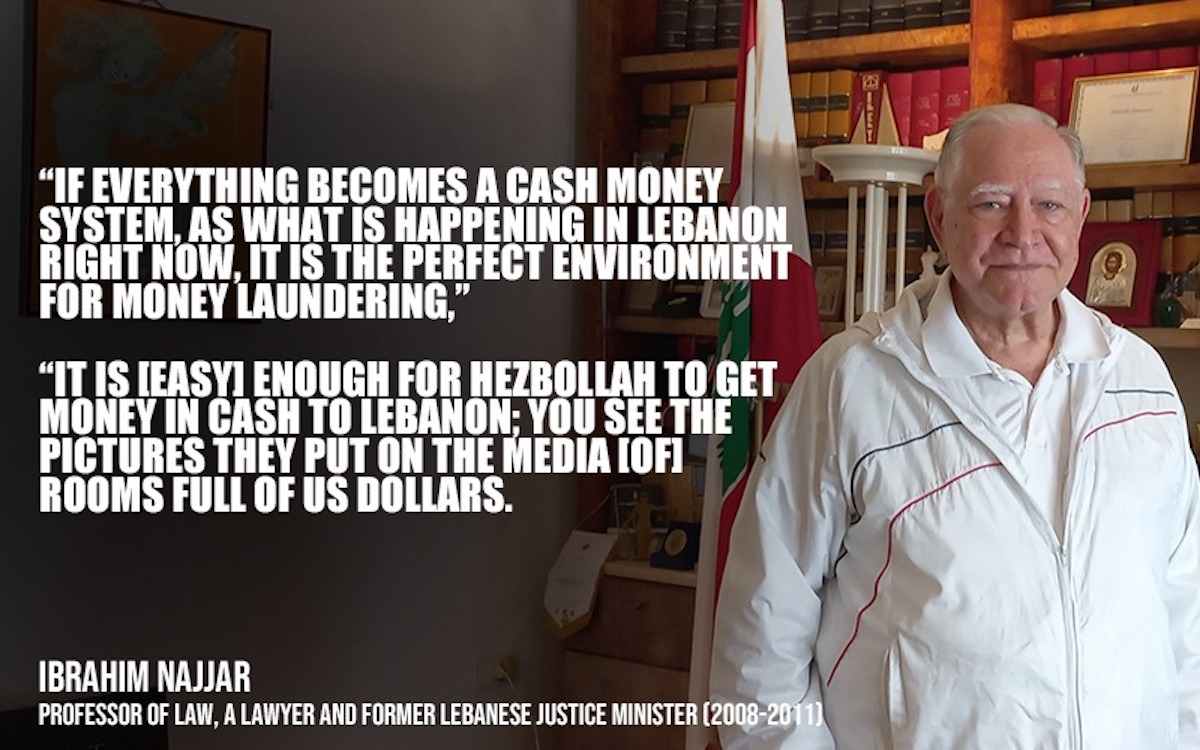

“We are silent, not doing anything,” Professor of law, lawyer and former Lebanese justice minister Ibrahim Najjar, an avid art collector, told NOW. “No one is talking about the Nazem Ahmad scandal. We need to do something. The [judiciary] should be responsible for this; the police [and] Interpol.”

“This is a whole world that is chaotic, and is so difficult to understand and comprehend, in which people are no longer afraid of the law,” he added. “You need a government that follows the rules. The law is important to protect the people, and put corruption to an end. A lot of people in Lebanon now are dealing with cash money since they do not have any trust in the banks. They are stacking their money in their houses.”

Lebanon’s banking secrecy law makes it difficult for authorities to investigate the accounts of those who may be engaging in illegal activities. While they were amended in 2022 in response to pressure from the International Monetary Fund to facilitate the work of government agencies, including tax authorities, the courts and the Banking Control Commission, there continue to be calls for them to be scrapped entirely.

Because Hezbollah has been designated as a terrorist organization in multiple international jurisdictions, many countries have outright banned transfers of money to the party, including Australia, Canada, Egypt, Japan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Hezbollah says that most of its funding is generated by donations and dividends from its own investments. However, it is widely believed that much of their income comes from backers in Iran, as well as from the sale of arms and drugs. This is then laundered through various fronts.

“If everything becomes a cash money system, as what is happening in Lebanon right now, it is the perfect environment for money laundering,” said Najjar. “It is [easy] enough for Hezbollah to get money in cash to Lebanon; you see the pictures they put on the media [of] rooms full of US dollars.

“They give a batch of money – cash dollars – to an individual; this money [is then used to buy] land or real estate, or artwork,” the former justice minister added. “Did Hezbollah send this money? Did the women that work for Hezbollah hide it in their veil or their clothes? It is possible. I have heard once that one of these women went to a notary, took $300,000 from her abaya and bought a house. They are looking for alternatives like these.”

Using art to conceal wealth and launder ill-gotten gains is a historically well-known practice, as the sector’s tendency towards discretion and preserving the anonymity of clients means that pieces can be sold across national borders with comparative ease, without much in the way of tractability.

“The opaqueness of this market makes it very easy to use it to launder your money or to evade taxes,” Maalouf Abi Younes and Tohme Law Firm lawyer Julien Maalouf told NOW. “It has been used since the beginning of the 20th century. Russian oligarchs often do that. It was used by the Nazis during World War II when they stole pieces owned by Jewish families in Europe in order to finance themselves.”

“Everything is usually trusts or shell companies,” he continued. “You can never know who has possession. You can have a historic piece by a major artist that is simply out of circulation. People often use hangers and free ports in order not to pay taxes and, most importantly, be inaccessible for authorities.”

The subjective nature of value in the art market also makes it highly susceptible to manipulation. Works previously estimated as low-value can have their prices rapidly elevated by a more favorable appraisal or interest from a potential purchaser willing to offer a larger payment.

This can also be exploited in conjunction with the fact that clients of auction houses are able to buy and sell without disclosing their identities publically, allowing bad actors to manufacture ‘sales’ that radically alter the perceived value of the assets being sold with minimal oversight or restrictions.

“A very common practice is to buy several pieces from one artist, put one at an auction, and then use contacts and intermediaries to pump up the price of the piece at auction,” said Maalouf. “[By effectively acting as] the buyer and the seller, they get the piece back, while also driving up the prices of the other pieces they bought.”

“Buyers and sellers are often anonymous and, in general, art galleries don’t have the means to evaluate the compliance of their clients with the law,” he added. “Big auction houses have the means to do their due diligence concerning their clients, but they usually won’t do much more than saying that they will comply with applicable laws because they don’t want to put their business at risk. They could lose clients and – therefore – big sums of money.”

Some steps have been taken in recent years to stop these practices from happening, often in the form of controls imposed on cash transactions. Authorities are slow to act on the majority of these cases however as – again, due to the lack of transparency in these markets – few ‘suspicious’ transactions are reported.

Certain countries, like China, do not place any restrictions on transactions at all, making it an attractive market for both legitimate and illegitimate art dealers.

This lack of oversight also permeates another aspect of the cultural sphere that Hezbollah utilizes to enrich itself: the trade of looted antiquities and cultural artifacts, many of which are taken from neighboring Syria.

The theft and trafficking of antiquities is nothing new and is often associated with conflict. However, with the advent of social media, it is becoming increasingly easy for those with stolen goods to sell to make contact with buyers, enabling a face-to-face, cash-sale business model that is very difficult for authorities to effectively police.

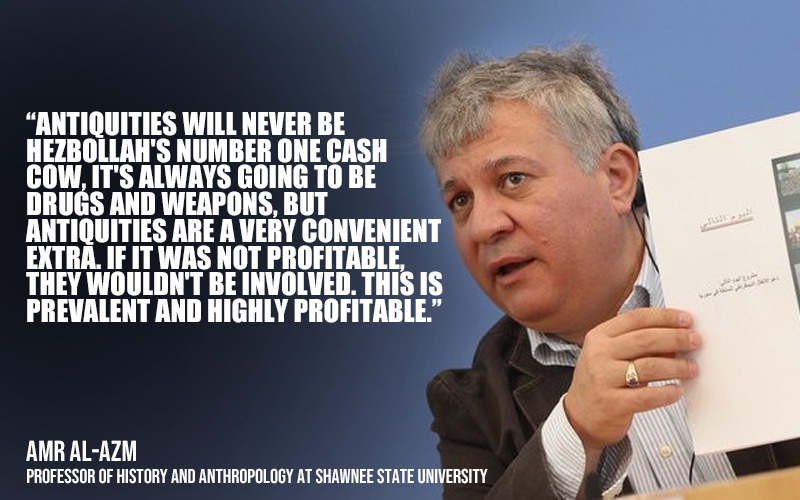

“Border areas have always had smuggling networks,” Amr al-Azm, Professor of History and Anthropology at Shawnee State University, Ohio, USA, told NOW. “The entire Lebanese-Syrian border area is riddled with donkey trails that have been known for centuries. You load them up and send them walking, and they know their way by themselves; you’ll send them off when it starts to get dark and by dawn, they’ve arrived on the other side. Hezbollah happens to control a lot of these areas now, so therefore the smuggling routes are under their control.”

“Early on in the [Syrian Civil War], Hezbollah became a part of the conflict and disrupted the traditional smuggling routes for those further inland,” he explained. “If you were somebody who had goods to sell, you can no longer move your goods, [but] Hezbollah – or somebody allied with Hezbollah – could easily buy from you.”

“Throughout the war, on the contact points between the rebels in opposition-controlled areas, there was a major crossing point and, on the other side, you had Hezbollah,” he continued. “There was constant traffic. [When] cultural goods were looted from other areas of Syria, they would be transferred across to Lebanon, and then from Lebanon, they would be shipped out.”

Hezbollah’s access to Lebanon’s free ports of entry and exit allows them to then pass these stolen artifacts to their accomplices overseas. The organization has a significant degree of control over many of the relevant authorities through their MPs and ministers, and those they do not control are either indifferent or ineffective.

Buyers also often travel to Lebanon to make purchases, due to generally warmer relations with the West than other regional countries, facilitating access to Western markets.

“There is illegal trading in most Western European countries in the sale of antiquities,” said al-Azm. “There’s a lack of scrutiny in many cases. There’s no incentive on the demand side to produce these harsher legislations because they’re the beneficiaries [and it] would harm their businesses.”

“You have a market that – because of its opaqueness and passivity, and because of the lack of severe sanctions legislation – shifts [responsibility] onto the buyer to do their due diligence,” he explained. “It should be the auctioneers that have to be responsible for ensuring that what they’re selling is legally exported.”

The scope of Hezbollah’s antiquity theft in Syria is significant and sophisticated. ISIS is known to sell permissions to perform looting exhibitions in areas under its control, and Hezbollah has been documented hiring crews and heavy machinery to undertake large-scale excavations. They also bring in experts to assist in the evaluation of their finds.

“Antiquities will never be Hezbollah’s number one cash cow,” said al-Azm, but added that they do provide an extra form of income.

In spite of the actions taken by the international community, Hezbollah remains largely untouchable in Lebanon’s culture of tit-for-tat sectarian factionalism and political corruption. Few are willing to openly criticize the organization for fear of reprisal or being socially isolated by their peers.

At the same time, Hezbollah’s significant base of supporters decries any attempt to investigate their alleged criminal activities as attacks against the Shiite Muslim sect they claim to represent, fuelling the seemingly interminable deadlock of Lebanese politics.

“Lebanon is ruled more by corrupt people than Hezbollah,” said Najjar. “[They] do sketchy deals where they get loans in Lebanese lira and buy US dollars. They launder money by buying real estate, and they benefit from loans from the Central Bank. Hezbollah is not the main problem, but part of the problem. There are a lot of people involved that benefit from the crisis. I will not name names, because I don’t have proof.”

“The arts and culture world is a part of the corruption that is happening today, [with] its own privacy policies and rules,” he lamented. “All the gallery sellers know who they are selling to – even if it was for Hezbollah – but, again, nobody is obliged to say who they are or how much credit they have in the bank.”

Throughout the writing of this report, many art dealers and experts in Lebanon were approached to comment and to anonymously provide information about the underground world of laundering money through art. None were willing to do so, as they are the brokers to acquire these works of art and sell them to the likes of Ahamd. In addition, according to an anonymous source, Ahmad and others with similar profiles have also been buying arts from young and upcoming artists and inflating the prices in order to create a market that can be used to launder money at a later stage.

Earlier this year, Lebanese authorities were compelled to return more than 300 illegally obtained archaeological artifacts to the Iraqi government that were previously exhibited in Lebanon in the collection of the Nabu Museum, founded by businessman Jawad Adra. Many of their acquisitions are of questionable provenance, and the museum itself was partly built on coastland supposedly marked as a public beach, which should have made it illegal to construct anything on it.

Adra – who is also married to former Defense Minister Zeina Akkar – denies any wrongdoing and rejects the claim that these tablets were bought from ISIS. However, both Adra and Akkar were the subjects of an Interpol red notice, asking law enforcement agencies around the world to arrest them. Adra also owns an extensive collection of looted Arab artifacts taken by Moshe Dayan, an Israeli military commander and former Minister of Defense who participated in both the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the 1956 Suez Crisis.

A picture taken on February 8, 2022 shows a tablet displayed at the Iraqi National Museum after it was returned by a private museum in Lebanon. – More than 300 ancient cuneiform writing tablets were returned to Iraq on Monday from a private Lebanese museum, as part of Baghdad’s widespread efforts to restore antiquities looted during years of war. (Photo by Sabah ARAR / AFP)

Hezbollah has consistently found ways to circumvent the laws intended to restrict their access to funding, from smuggling to running drugs and money laundering, contributing to an international network of corruption and crime that benefits only a select few individuals. However, the trade of art and antiquities offers them the ability to conduct business almost in plain sight, with minimal repercussions for those caught acting on their behalf. Without more strenuous regulations – and proper punishments for those breaking these laws – this will continue, ensuring that groups like Hezbollah will always have access to a lucrative marketplace.