When the timing is just right (see ‘Stuck in Time’) – and the moonlight shines over an urban landscape that is ghostly and haunting – Beirut’s book opens its missing chapters.

More like a story’s neglected passages. Blending our collective memory-turned-amnesia through more recent times.

When I used to give my WalkBeirut tour I made it a point – with every single group – to enter Wadi Abu Jmeel. The amount of phone calls, security checks and persuasion needed (along with endless questions by security guards that monitored the guests) made it both immensely frustrating and equally rewarding.

The frustrations are the unnecessary hurdles we go through to simply live in this city. The reward, at least for me, was bringing history to life. In the heart of Beirut, looking beyond Nejmeh, the terribly reconstructed (and meaningless) Souqs and the senselessly hollowed and scarred Martyrs Square to reflect on our metropole’s once beating pulse that pulled the region’s brightest and sheltered minorities in a geography defined by delicate consensus and communal power-sharing.

Our mosaic is missing components. Some were erased, entirely. Including downtown’s Jewish quarter.

Entering the neighborhood, today, it feels (and mostly is) abandoned. Earlier French Mandate-era architecture that survived the civil war was knocked down in more recent years, making way for redesigned luxury condominiums that were finished yet left empty long before the recent economic collapse or the port blast. Mimic-like replicas of older (and once inhabited) homes look better in a sprawling Doha or Dubai than our naturally limited downtown district.

As for the current inhabitants? A few diplomats and their security entourage live next to the Grand Serail, along with whoever still frequents Bayt al Wassat.

Most Lebanese guests that joined the tour had never been in Wadi Abu Jmeel, or knew of the neighborhood’s existence. Driving past Starco between Qantari and Bab Idriss on its northern end is easy. Approaching the Roman baths from above at the intersection of Bank Audi’s downtown headquarters towards its eastern flank was possible until October 17. Noticing the Grand Serail at the top of the hill that overlooks both ends is something we all do.

But the vast stretch in between is mostly hidden from view. And therein lies Al Wadi – Valley of the Jews.

A rich history

You would never know that Wadi Abu Jmeel was once thriving and predominantly Jewish. Bustling with supermarkets, small family-run enterprises and two Jewish schools – Alliance Israelite and Talmud Torah, the latter overlooking Maghen Avraham Synagogue. A majestic temple, built in 1921, served a growing Lebanese Jewish community in Greater Lebanon’s newly established capital, arriving from Tripoli, Saida and Deir al Qamar.

A working-class district, as well, almost unthinkable in Solidere’s reimagined Beirut. I did a podcast episode trying to capture some of those memories (see ‘Al Wadi’) with Lebanese Jews from different generations that are physically disconnected, despite their emotional ties and a longing to return.

Maghen Avraham was renovated after the civil war – and a second time following the port blast. It remains locked (there are not enough Jews to congregate let alone a Rabbi to administer service). And today, it is one of only two reminders of the community’s belonging to Beirut.

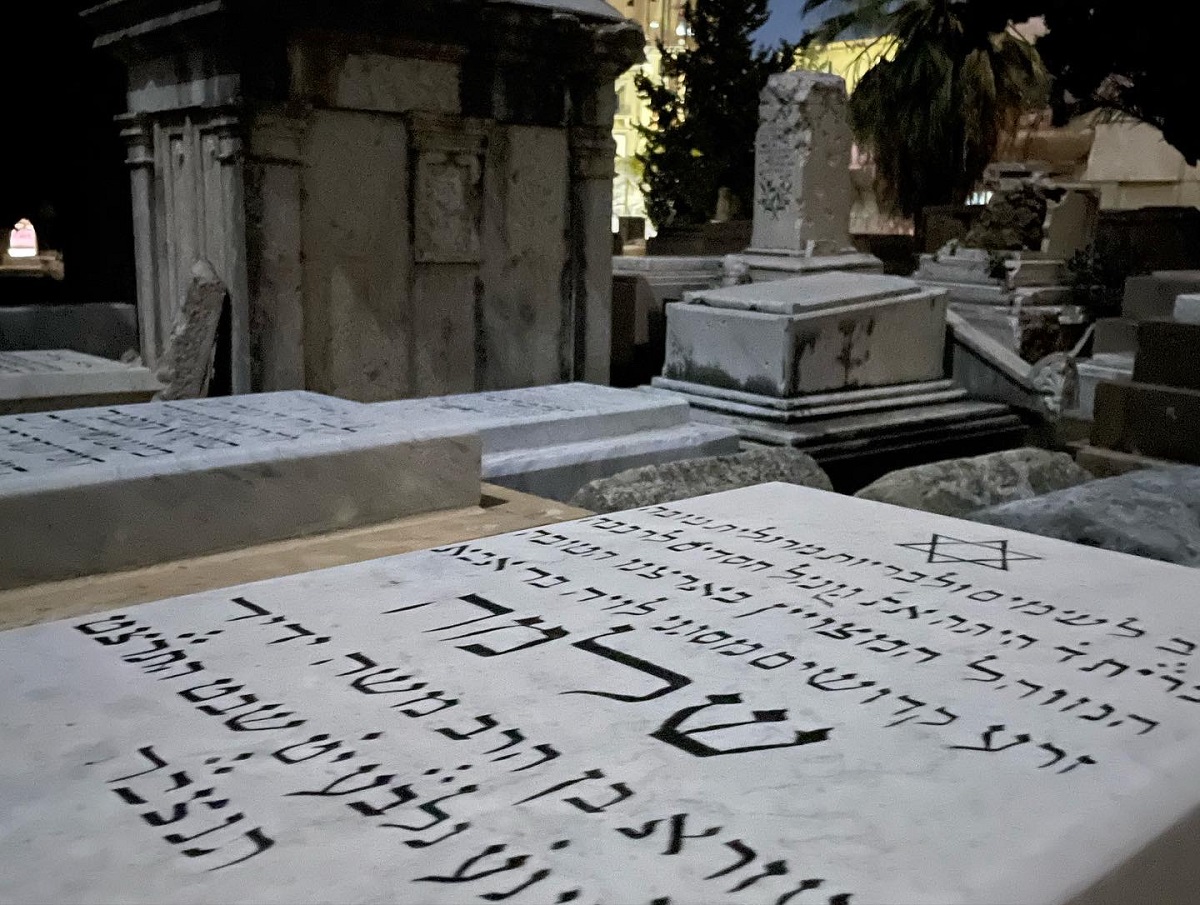

The second, near Sodeco Square, along the former Green Line, is where this piece begins. The Jewish cemetery of Beirut was exposed nearly two years ago when heavy floods damaged and brought down a retainer wall along Damascus Street.

And with that fall, graves of Lebanese Jews that departed decades past were tossed onto the road for weeks until a new wall was erected.

Rather than left to rest in peace, drowning with the rest of us in despair.

The departed

It is startling to see Hebrew anywhere in Lebanon, with stars of David adorning tombs that have withered through decades of civil war and decay. Some of the writing is solely in Hebrew, but the majority of graves have names and dates inscribed in French and Arabic alongside Old Testament verses.

I will skip the details of how I walked in, but the cemetery is not maintained in any serious way. The passageways are bent to roots pushing through the earth into cracked cement, beginning at an elevated and newer burial site built during the Mandate and expanded during early independence, joining the older Ottoman graveyard further south and below. Some of the marble casings are new – a Lebanese Jew living in New York messaged me on social media after I posted my visit, sharing a photo of his great grandmother’s recently repaired tomb (she passed away in 1960). His father was the last of his family to reside in Lebanon, leaving in 1983.

The community gradually joined other Lebanese in the diaspora, and most made their way to France, Canada and the United States.

Not Israel.

An important fact, that unlike other Arab Jewish communities that comprise half of Israel’s Jewish citizens, the overwhelming majority of Lebanese Jews did not seek refuge there (see Kirsten Schulze’s ‘The Jews of Lebanon’). In fact, Lebanon was the only country aside from Israel that saw an increase in its Jewish population after 1948, with Syrian and Iraqi Jews fleeing to Beirut. The 1958 civil war saw the numbers begin to decline, and with the 1967 war’s repercussions, the population dropped to the hundreds. The civil war, with kidnappings and assassinations of community elders, forced the few that chose to go into hiding. And today, while exact numbers are unreliable, it is hard to imagine more than a handful still living in this county.

When I began writing for NOWLebanon in early 2008, my first piece was an interview with the last Lebanese Jew then residing in Wadi Abu Jmeel – Liza Nahmoud Srour, who passed away in 2012. We explored her own relationship to Lebanon and why she never left, and I had learned she was buried in the cemetery.

I spent the better part of that night looking for her name…with no luck.

On my way out, I stumbled upon what looked like an entirely replaced tomb. The name glistening in the moonlight: Khalil Cohen Ajami, who passed away on February 16, 1967. The same date I was standing there, 55 years back. And four months before the Arab-Israeli conflict would begin shifting from Egypt, Syria and Jordan into Lebanon, eventually destroying Beirut, tearing the city in two, and placing the cemetery on a dividing line that ended a brief moment of time.

And the window I keep turning to, despite the gathering dust.

His name, like Liza’s, speaks volumes. The first and last shared among a multitude of faiths that mingled along the eastern Mediterranean. The middle narrows us naturally to the region’s hinterland and narrative threads.

Thinning above the cracks, perhaps, but still visible when you search.

And to my mind, the best chapter of our story ever written or told: a geography layered in history, complicated in identity and rich in diversity. Where all of us felt at home.

Ronnie Chatah hosts The Beirut Banyan podcast, a series of storytelling episodes and long-form conversations that reflect on all that is modern Lebanese history. He also leads the WalkBeirut tour, a four-hour narration of Beirut’s rich and troubled past. He is on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter @thebeirutbanyan.

The opinions expressed are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOW.